Under the Red Top

making the best of life & woodTickin’ Francese

An Ansonia Clock Co. advertisement (c. 1900)

Get it? Tickin’ Francese? Oh, but I do crack myself up! Which is a good thing too, for sometimes I’d swear I am the only person who appreciates my Dad puns (heh, heh … wait …). Anyway, this post is about the Americanization of a classic French entrée clock.

In addition to the dozen or so clocks scattered about the house and workshop that tell time I also have a small collection of antique clocks that tell stories. These wonderful objects, five in total, were collected over the past quarter century as my interest in clocks developed. Four of the five are operational and while they all have special meaning for me, no clock in my collection would be particularly valuable to anyone other than me. My favorite, a late nineteenth century French marble clock, has been keeping our living room on time for the past 18 years. I recently did some digging into the history of that French clock and, like most research efforts, this revealed some unexpected insights.

French marble clock with Abraham Lincoln, a contemporary.

While it is easy (and fun) to study the general subject of “time keeping”, researching clock devices in any depth is more of a challenge. Books on clocks tend to be either pictorial encyclopedias, manufacturer’s sales catalogs or repair manuals. A few general histories are out there, and I found Eric Bruton’s The History of Clocks and Watches to be a delightfully informative reference. But to dig deep into any particular clock the internet is probably the best option; spade that turf long enough and one can accumulate a good pile of consistent-ish information. There are also a few clock repair gurus on YouTube who share their knowledge of these once indispensable, now venerable relics with loving zeal (kinda like that high school Latin teacher) and I invite you to check out Time4clocks as an example. Those are my sources for the following tale.

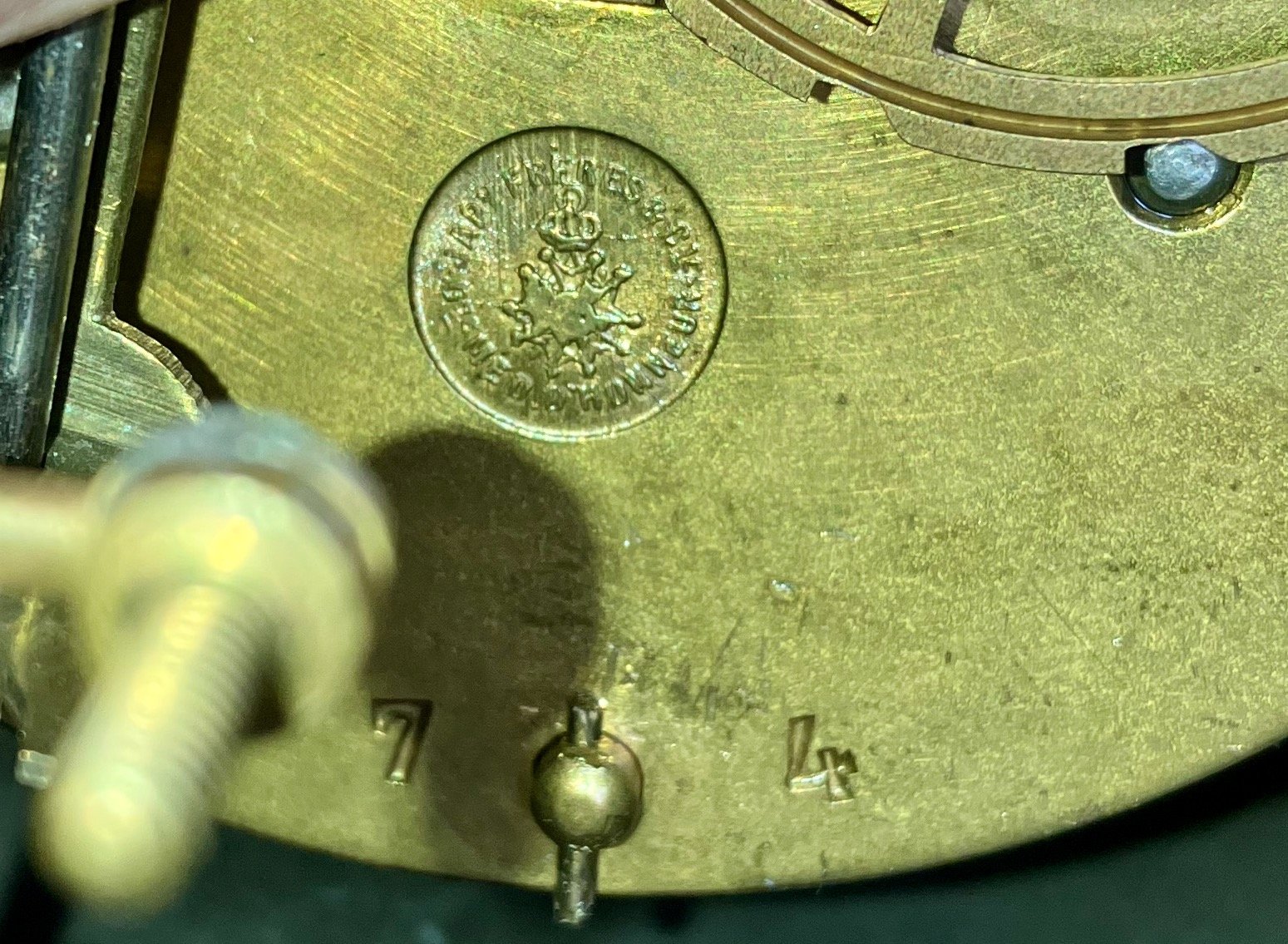

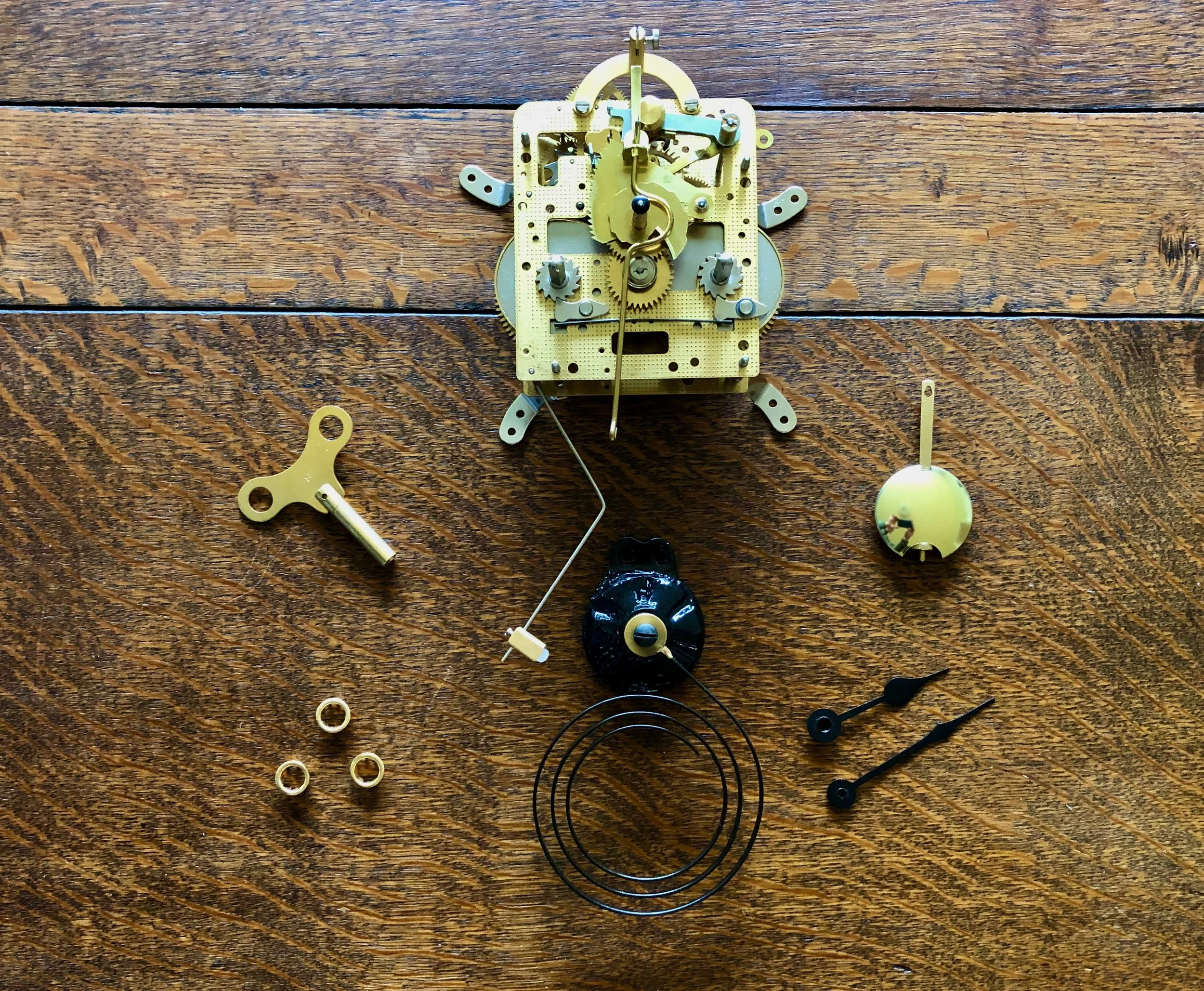

The plot line is a comparison of clock cases, but the story begins with a desire to understand the history of my particular French marble clock, and for that we need to examine the clock works. That is where the maker and date can be established. Of the many clockmakers producing the distinctive pendule de Paris (clock of Paris) movements in nineteenth century France, mine was made by the most prolific: Japy Frères et Cie (Japy Brothers & Co.). According to this source, in 1806 the Japy brothers, three sons of the industrial pioneer and clock making giant Édouard Louis Frédéric Japy (1749-1812), inherited a first of its kind, single site manufacturing operation for clocks and all of their parts. This firm dominated Europe’s clockmaking world for decades before their over-diversification into products such as typewriters and bicycle parts nearly drove them into the ground. During their heyday, however, Japy Frères made a wide variety of strikingly beautiful timepieces, and among these are the family of so-called black marble clocks. Googling that descriptor gives you an idea of the diversity of production for just this one style.

As far as I can tell, my particular specimen dates to the 1890s. This was determined by inspecting the backside of the movement, ignoring those serial number-like red herrings stamped all about, and interpreting the logo that changed over time depending on which new clockmaking award the brothers chose to plug.

‘Clock of Paris’ movement backside (bell and pendulum removed)

Though certain features, such as the Brocot escapement and exposed count wheel, are characteristic of an earlier era the logo on my movement, declaring the “Gde Med. D'Honneur" (Gold Medal of Honor), was apparently used from 1888-1900. However, given the tenuousness of this dating method, my personal language barrier and the general hazards associated with internet sleuthing, it would not surprise me if it is a decade or two older than that.

Logo close up

Black marble clocks were wildly popular in Europe and Great Britain. And as a nation of immigrants with a fondness for Old World tastes, they were sought after in the U.S., too. Somehow my clock made it across the Atlantic and, ultimately, to a clock shop in Hightstown, NJ where I purchased it in 2005. However, most nineteenth century Americans had to make do with the local fare. The so-called black mantle clocks, presumably a welcome diversion from the prevailing brown wooden cases, were top sellers and all of the big U.S. companies had their line-ups (e.g., Ansonia, W.L. Gilbert, Ingraham, New Haven, Sessions, Seth Thomas, Waterbury). And while some companies imported marble for these, most cases were made from substitute materials. To mimic the French stained marble (largely quarried in Belgium, as it turns out) those crafty Americans used a process called “japanning” to put a black enamel coating on either a wood or metal clock case. Seth Thomas also employed an early type of celluloid plastic, called “adamantine”, to veneer a flat black or even a fake, so-called “marbleized” finish to wooden cases. Resourceful!

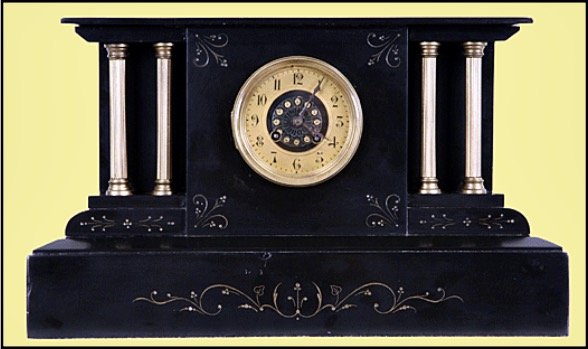

After learning about my French clock and its influence on contemporaneous American designs it dawned on me that two of my other antique clocks fell into this same family. The first is a stout Ansonia metal clock, also acquired in New Jersey, that graced the mantle of our lake house there for many years. Purchased in 1998, it dates from the 1880s and was one of the many many black mantle clock designs produced by that firm, founded in 1850 by Anson G. Phelps. I had the 100-year old movement cleaned and oiled at that time and it is still running strong. The dial and hands have been replaced over the years, but that is not uncommon for heavily used clocks. On first glance it bears little resemblance to my bone fide marble clock but it does possess the characteristic brass rimmed, flat glass bezel, the telltale botanical engravings and it was, of course, black.

My Ansonia black mantle clock c. 1885

The movement is visible from the backside beneath the circular cover. Like all American varieties the works are less space-efficient than the pendule de Paris, but sturdy.

Ansonia movement, patented June 13, 1882.

For marketing purposes, many clocks were given names and this one, ironically, was called “Unique”. The case turned out to be a close copy of another one of Japy’s marble clocks. In fact, if you invert the top it is a dead ringer - in enameled iron.

Japy clock c. 1860

(reproduced from liveauctioneers.com website)

The second American black mantle clock in my collection comes via Michigan and my departed Uncle Chuck’s estate. I wish I knew more of its provenance and whether he may have inherited it from an earlier family member but all I can uncover is its horological history. The tattered label identifies it as a clock made by the Sessions Clock Co. This Connecticut company was formerly the E.N. Welch Manufacturing Co., which lost so many assets during a series of factory fires that they eventually had to sell to a smaller firm and was renamed “Sessions” after the new head, William E. Sessions. Perusing the history of various clockmakers it seems that fire was a major “selection event” driving their evolution, worldwide. Apparently, Frédéric Japy’s successful legacy of co-localizing all operations to enhance productivity/affordability also made clockmakers more susceptible to sudden catastrophe.

Back to our story, this early Sessions clock has a black enameled wooden case that possesses fine engravings and an exquisitely ornate dial housed within a brass (or brass-like), flat glass bezel. As with similar clocks from that era, the case is loaded with other metallic gimcrackery. Some of this was meant to imitate bronze features gracing their French counterparts, but the rest appear to be an American fling with rococco-ism that probably merits further research to determine exactly what they were attempting to accomplish. Still, it is a stately looking object on my shelf with a dear familial connection and, unfortunately, a sprung mainspring.

My Sessions black mantle clock, c. 1905

Remnants of the original label

Since the label still references the E.N. Welch heritage, I date the clock to near the corporate sale of 1903. A cursory Google search, once again, turned up its marble doppelgänger of a slightly earlier period.

Japy clock c. 1880

(reproduced from harpgallery.com website)

So that is the story of three black mantle clocks of common pedigree. Variously produced some 120-150 years ago in France, New York and Connecticut, and after some traveling about they now all reside in my Massachusetts home. That’s quite a testament to influence if you think about it. The design of this French clock was so powerful that it was copied across the globe, spawning a multitude of facsimiles wrought from local materials and produced by the millions to be traded even more widely, yet all striving to be the black marble clock. Individually, these clocks are now treasured as heirlooms. Much like a beloved family recipe, they were selected to satisfy a long ago taste, enjoyed in their time, transported across international and state boundaries, and handed down for succeeding generations to partake. Bon appétit!

Clock No. 1

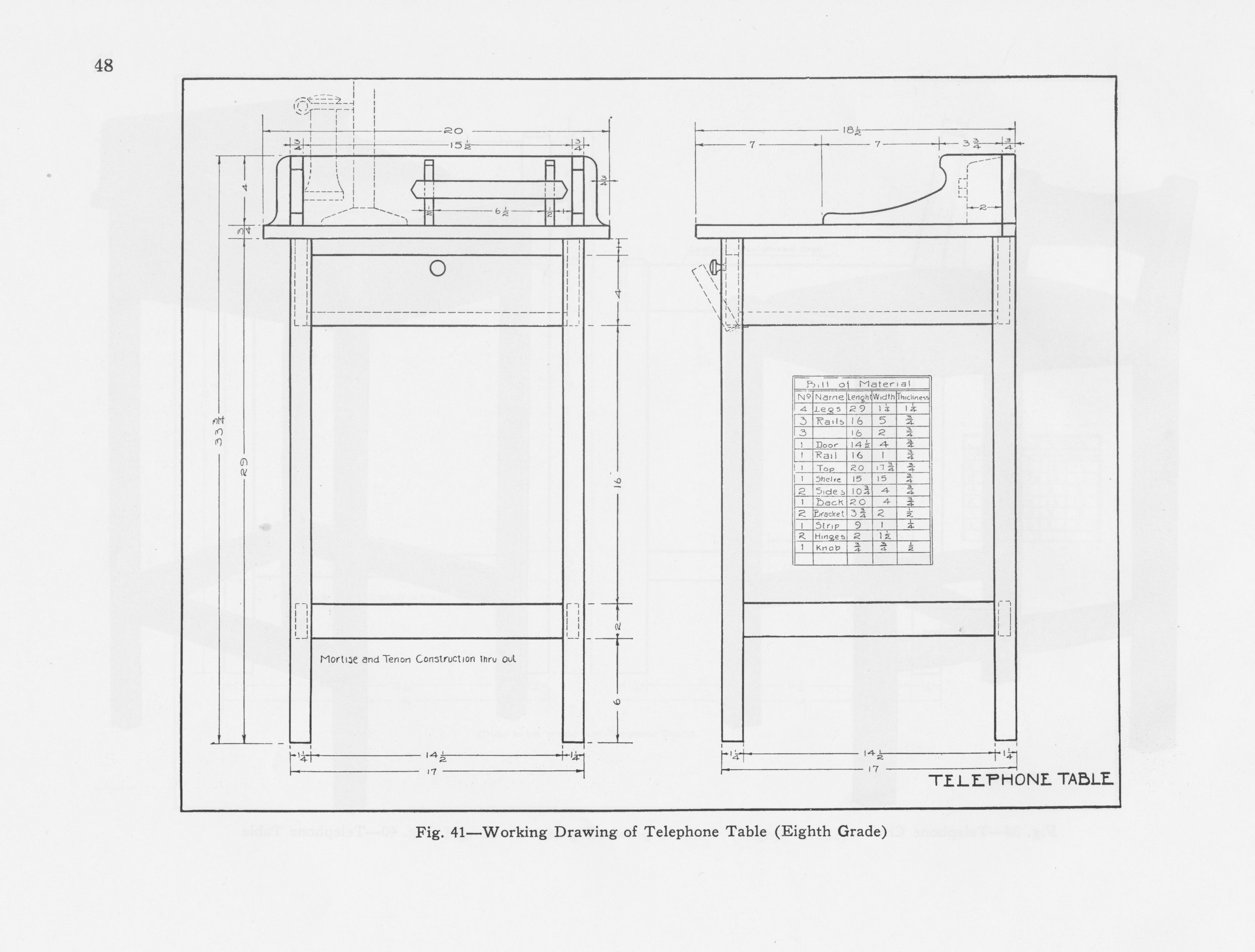

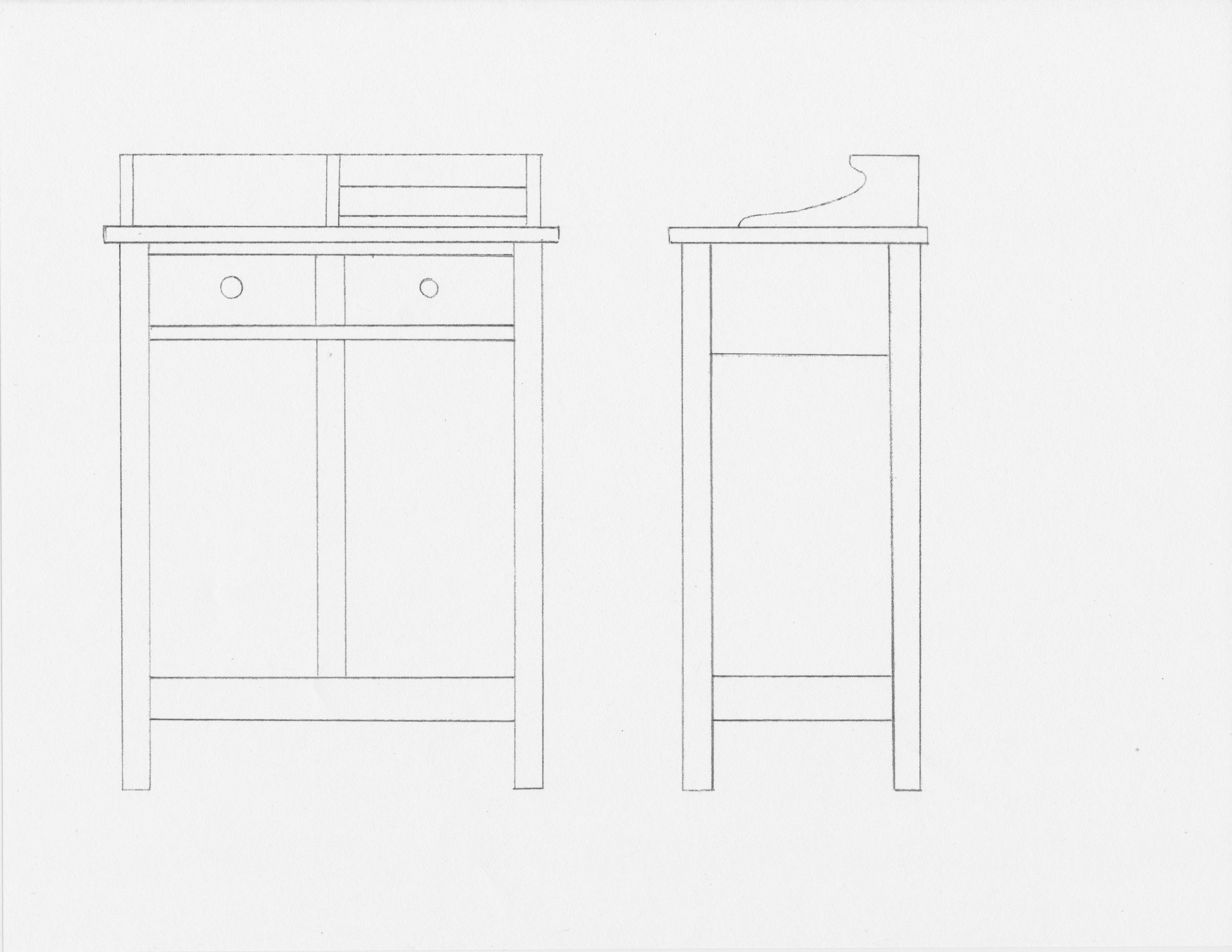

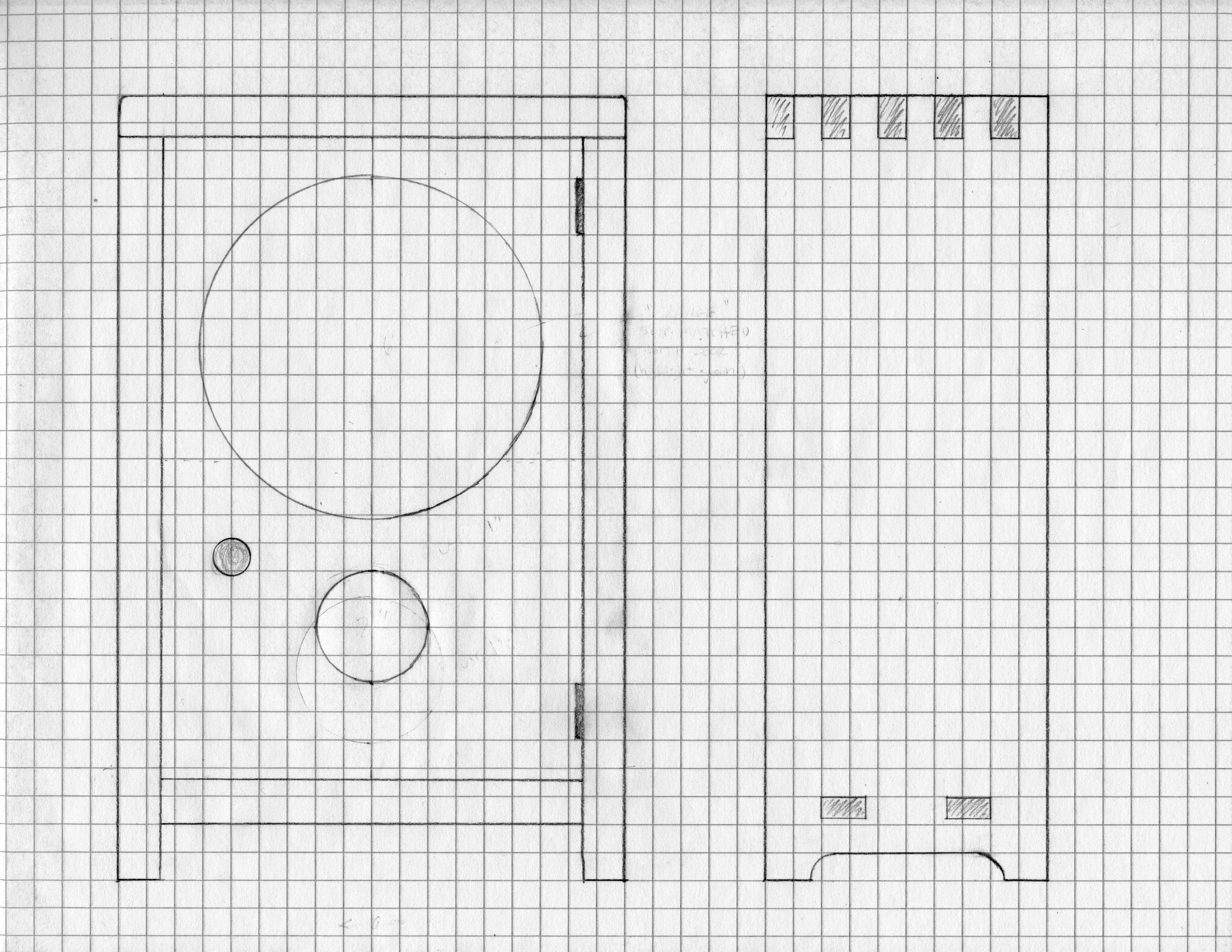

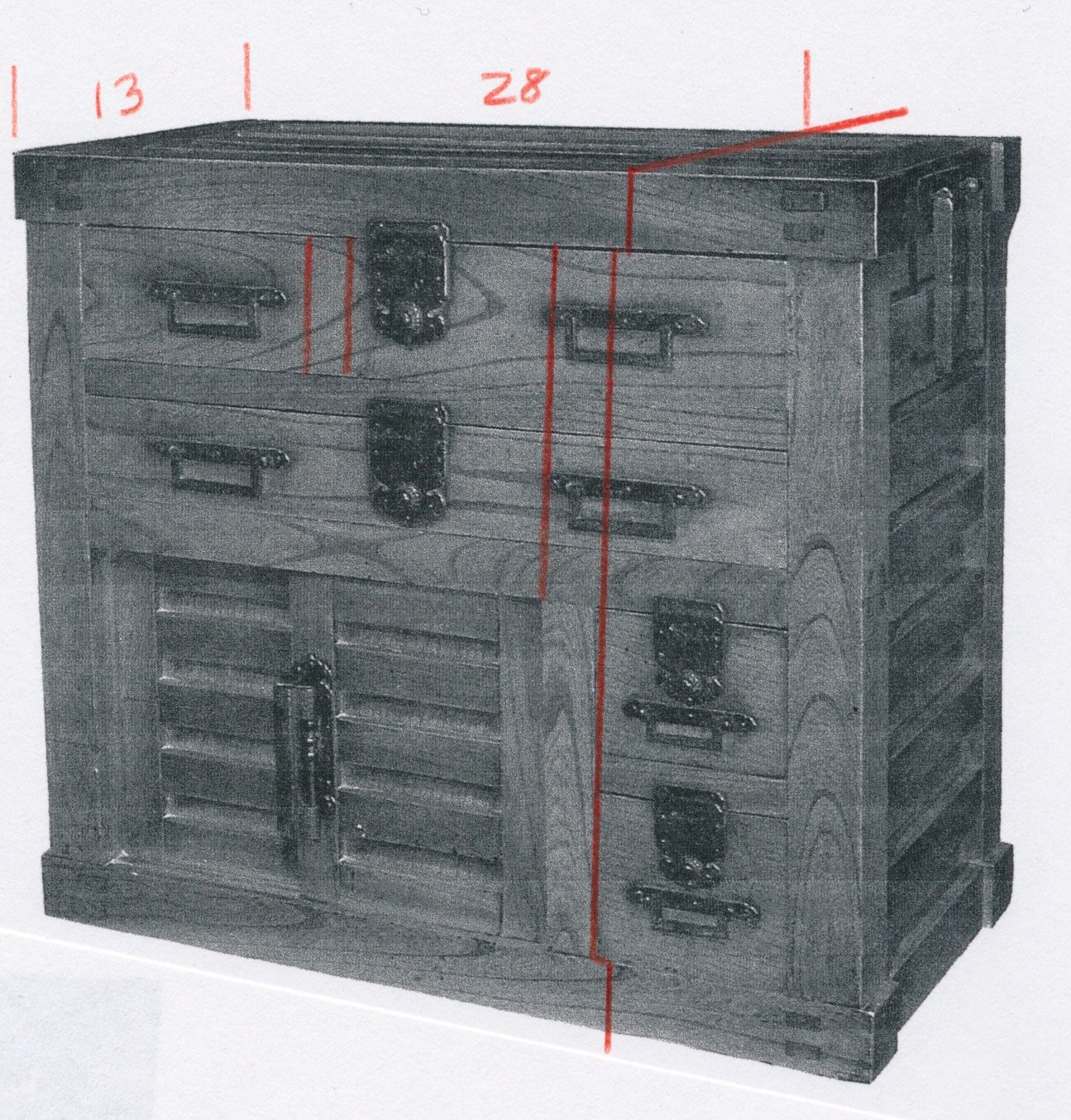

I have been fantasizing about clocks a lot lately. They are fun to dream of while working on heavier things. I keep a list of the ones I’d like to build some day that continually shuffle in their mental order of construction, mostly early American classics. Of course, the desire to make a clock completely of my own design is there too, and recently I decided to convert some doodles into a drawn plan. I was looking to make a shelf clock that could serve as a housewarming gift for good friends of ours, and what I was trying to create was a timepiece that could be used in any room. This small clock required a simple case design and one that, although made of wood, would not look “old-fashioned”. It should also be a case that is easily constructed in the event I ever choose to duplicate for sale. Mission and Shaker styles both satisfy these criteria and I was hoping I might create something original that could fit within these canons. I call this design Clock No. 1.

Design

I favor elemental shapes in my wooden objects, things like right angles and arcs. These are disciplined features that, in concert with the material’s “untrained” texture, can achieve a satisfying harmony. Seductively curved mouldings and scrollwork have their place, but they too often compete with the natural character of wood. Circles, with some rectangular joinery will be the theme of this clock. Semicircles will define the bottom edges of the case and thereby create the feet. A box joint will form the connection between the top and sides, and I will do my best to hide the other seams so as not to distract. The clock’s back would be accessed via a door (hinged or sliding, TBD). And in place of numerals I could use dowel pegs made from the same wood as the case; the dark end grain should provide a pleasing contrast.

Clock No. 1 rough sketch

Materials

When building a clock the first decision to be made concerns the movement: mechanical or quartz? To wind or not to wind, that is the question, for clock case dimensions are affected by a mechanical movement’s bulk and pendulum swing. All else being equal, I prefer mechanicals for the life that these clocks bring to a home. But the current Project is for a vacation home and that changes things. I know from experience the sorry scene of opening the door to your retreat and being met by a “dead” clock on the mantle. Admittedly, it is an easy task for the clockwinder to resuscitate and then march the live timepiece through the gong sequence until it, once again, reaches its own meridian. However, this task begins to feel Sisyphean and grows old over time … quartz it is. Battery-operated quartz clock movements are easy to find and I picked one up at a new source for me, the Norkro Clock Co.

I can imagine that this clock would look nice in a variety of woods but, given that it is a lightweight clock with thin walls, I decided to use quarter sawn lumber to reduce the propensity for warp. That decision pretty much limits the choice to those woods commonly milled in this orientation, namely: oak, ash or cherry. I chose cherry.

Clock materials

Dimensioning

To begin, the 3/4 in. thick cherry board would need to be sliced into two thinner boards of 1/4 inch depth. This was accomplished by re-sawing in half at the bandsaw and then reducing these boards further (while flattening) to the exact dimension on a thickness planer. Next, the mill marks were removed using a card scraper and the grain patterns inspected carefully in order to assign stock-to-parts as artfully as possible (i.e., which portions of wood to use for the front, sides, top, bottom and back). Once labelled with tape, including interior vs exterior, the parts were trimmed to their proper widths at the table saw. During this operation both edges of the front and one edge of each side were cut at a 45 degree angle. During assembly these would all come together in mitered joints which, if executed properly, would leave an invisible seam.

After cross-cutting the front and sides to [proper height + 1/2 inch] it was time to cut the semicircular bottom edges. There are 3 common ways to cut circles using power tools and these involve either the router, drill press or band saw. I needed to make semi-circles of two different radii on small boards and for these reasons cutting at the band saw was chosen as the proper method. Way back during construction of the Stationery Chest I made a circle-cutting jig for my small bandsaw that has served me well ever since. Onto this jig, the boards were mounted individually at the circle centers with a bolt inserted at the exact height of the finished front or side piece (this is where the extra 1/2 inch comes in), the jig was slid into place on the band saw table and the board was then rotated in one smooth operation to slice out a perfect semicircle. Slick.

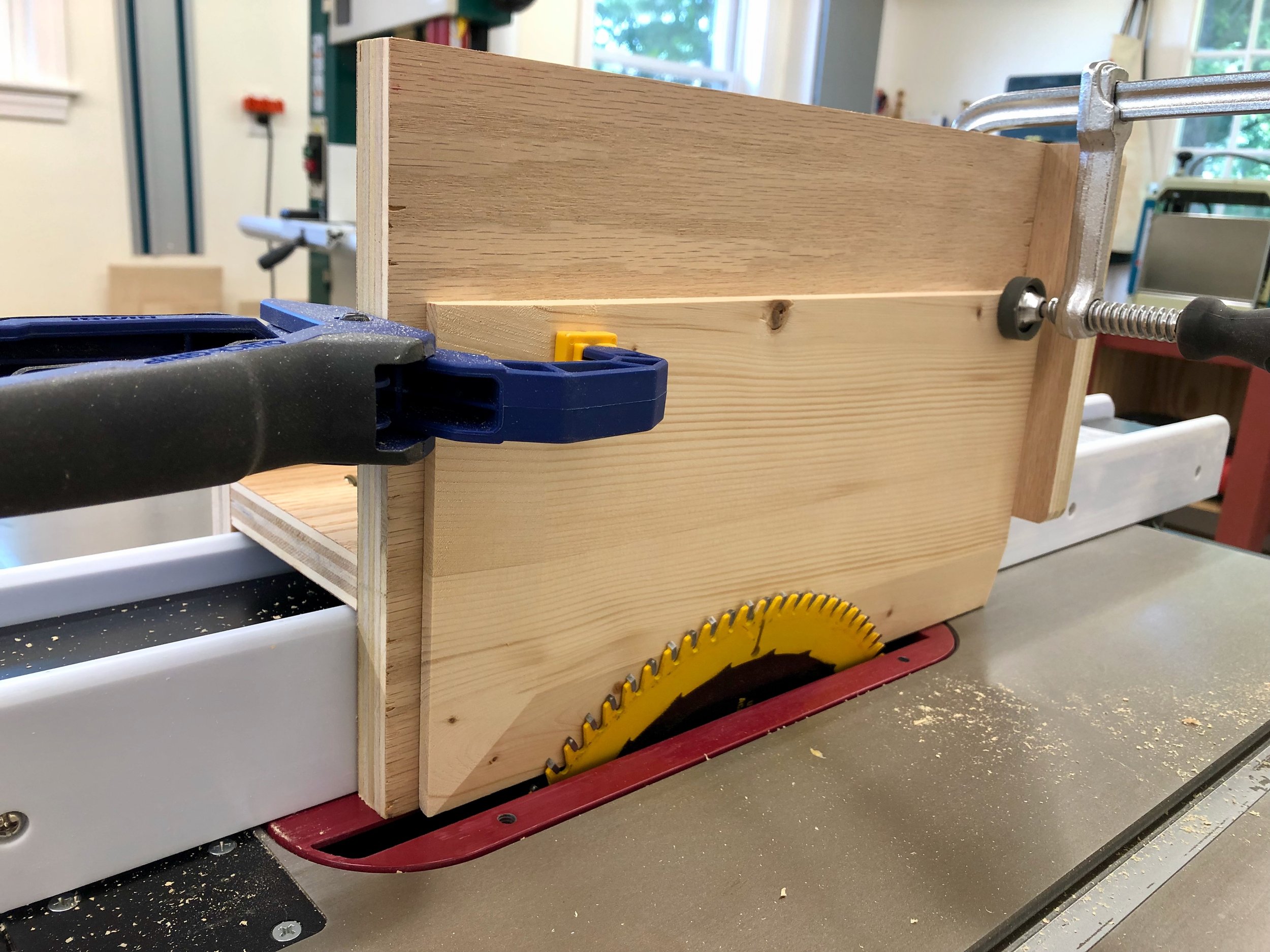

Cutting out the front board in a “clockwise” spin

Once the semicircles were cut, and the bottom 1/2 inch trimmed away, the next step was to fashion the box joint along the top and side pieces. I decided to use the table saw for this operation and this required that I first construct a new jig for the task. The “fingers” of this joint are small rectangles, 3/8 in. wide x 1/4 in. tall, which become the critical dimensions defining the new jig made along the lines of a larger version that I have described previously. This jig, used with a dado stack on the table saw, worked well to reproducibly cut the cavities at fixed distances along the joint edge. Taped together, both side parts were cut at the same time to ensure perfect alignment.

Cutting the box joint fingers

After the sides were complete, the fingers for one half of the top were cut-out. The sides and front were then dry fit and the top was dropped into place to mark its exact width, prior to sizing and then cutting the other half of the box joint. Next, the front edge of the top was trimmed back by the width of the front board so that everything would fit together properly. This happened to also be the width dimension for the interior shelf and so that was cut to size using the same fence setting at the table saw. The shelf, or bottom, is a structural element and would be supported by a shallow groove, easily cut into the side boards at the table saw using the cross-cut sled. The last part to fashion was the door which was cut from the remaining stock to fit the cavity of the dry-fit case. Since the door would have no structural support, I chose to rip the board in half and then glue it back together along the centerline. This corrected a slight bow and should help to ward-off future warp.

Clock case parts

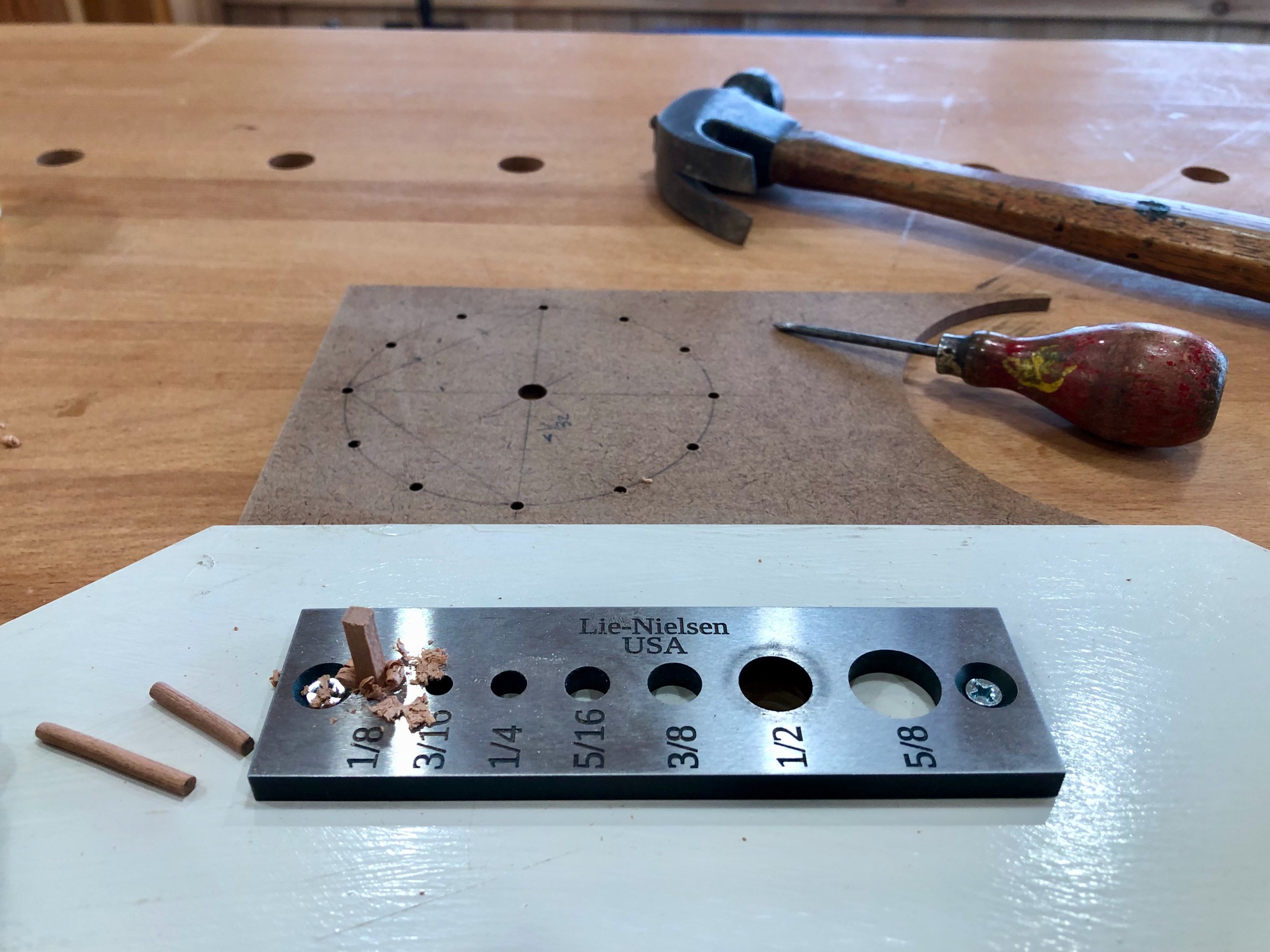

The final operation prior to assembly was to make the clock face. Holes drilled in a 4 inch circle surrounding a central opening would form the dial. These holes would then be filled with shop-made cherry dowels to take the place of numerals. Rather than draw on the face board, I first made a template of the dial on hdf material and then used this to guide a hand drill to make the production cuts. The dowels were fashioned with a dowel plate and hammer using cherry scraps.

Dowel-making with face template in background

With assistance from the template, the dial was created by drilling the 12-hole circle into the case front and then tapping a short dowel into each opening. A small dab of glue was applied to the back of each peg to secure these in place. The protruding ends were then removed with a Japanese flush cutting saw and the face sanded smooth to 220 grit. A center hole for the clock stem was then drilled to complete the clock face.

Clock face (bare wood)

Assembly & Finish

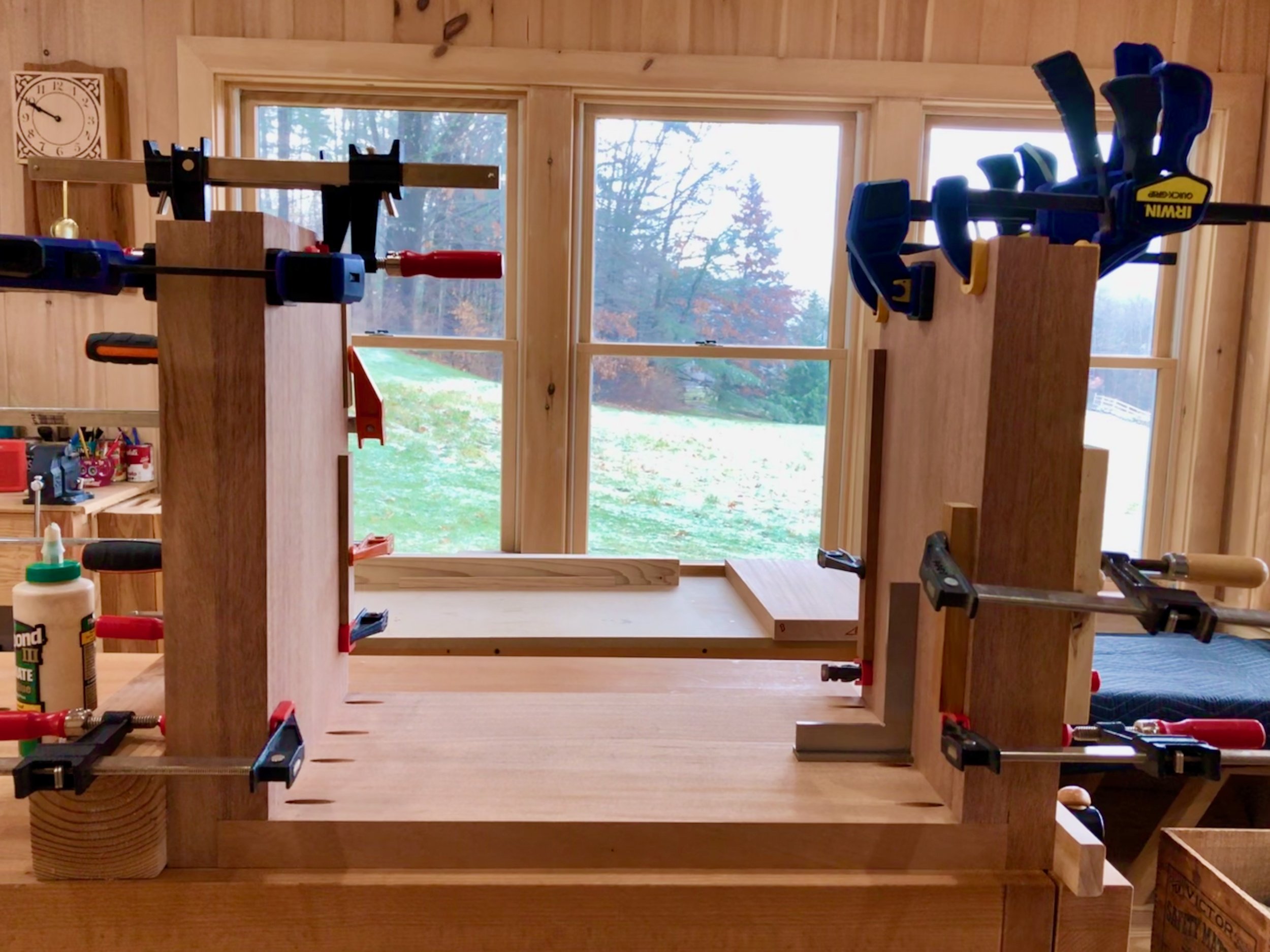

After sanding all of the parts smooth it was time to glue them together. The first step was to assemble the finger-jointed top and sides. These were put together as tightly as possible by hand and then the shelf board was slid into place and the whole carcass squared-up and cinched with clamps. Lying on its back, the structure could then receive the mitered front board which was aligned and clamped firmly into position. It is always difficult to snap a good picture during glue-up, the awkward disposition of clamps and devices evoke a scene in the dentist’s chair during an expensive procedure, but I tried my best in the below.

Case undergoing assembly

Unclamped, the case held together nicely but still required some grooming. The protruding box joint fingers were trimmed flush with a block plane, while the mitered edges were crimped to invisibility using a burnisher. I also trimmed the interior of the 1/4 in. thick sides (down near the bottom) so as not to interfere with the dainty statement of the 1/8 inch wide feet. A few joint gaps were beautified using thin cherry scraps and the whole carcass was then sanded down to 220 grit.

I chose to use hinges for mounting the door at the back of the case. Ultimately, the door will be attached following the finishing steps, but it is best to align and drill the screw holes at this point. I used the smallest pair of brass butt hinges I could find. As a handle I decided to simply drill a 3/4 in. circular finger pull. Clean.

Door mounted on the backside

Finally, I mounted a small rare earth magnet within the cavity that could mate with a hack-sawn screw to serve as the door catch. On to the finish.

I find the character of this wood to be fascinating and so I took some time to experiment with finishes, specifically comparing gel polyurethane with an oil-based wiping varnish (also polyurethane). I wanted to highlight the color variations in the wood, including the patches of punch card-like ray flecks, without inducing the blotching for which cherry is prone. I also wanted to maximize the contrast of the dowel end grain with the surface wood to make the face pop. Working on test pieces, I found that the gel polyurethane imparted a brighter, more orange, color to the wood, whereas the oil varnish gave a greener tint when compared side-by-side. The final surface was also smoother with the gel product (build-up filling the tiny valleys, perhaps?) and so this finish was applied to the clock case and door in three coats.

After the finish had dried, I attached the door hinges and then mounted the clockworks. The final design decision for Clock No. 1 was the choice of hands. The gold colored hands originally purchased for this clock turned out to be too bright, with not enough contrast against the wooden face. I liked the style, but not the finish and so I procured a similar set of hands in black. These did the trick!

Clock No. 1 face

I like this prototype clock and think it has some staying power. That little nine inch timepiece has a presence. The cherry wood provides intricate grain on a scale that does not overwhelm a small item, although oak would also be nice and I now think mahogany would be a rich material to try, as well. I have some ideas for making the joints appear “cleaner” and to also simplify the door mechanics, too. Lots to explore! - next time.

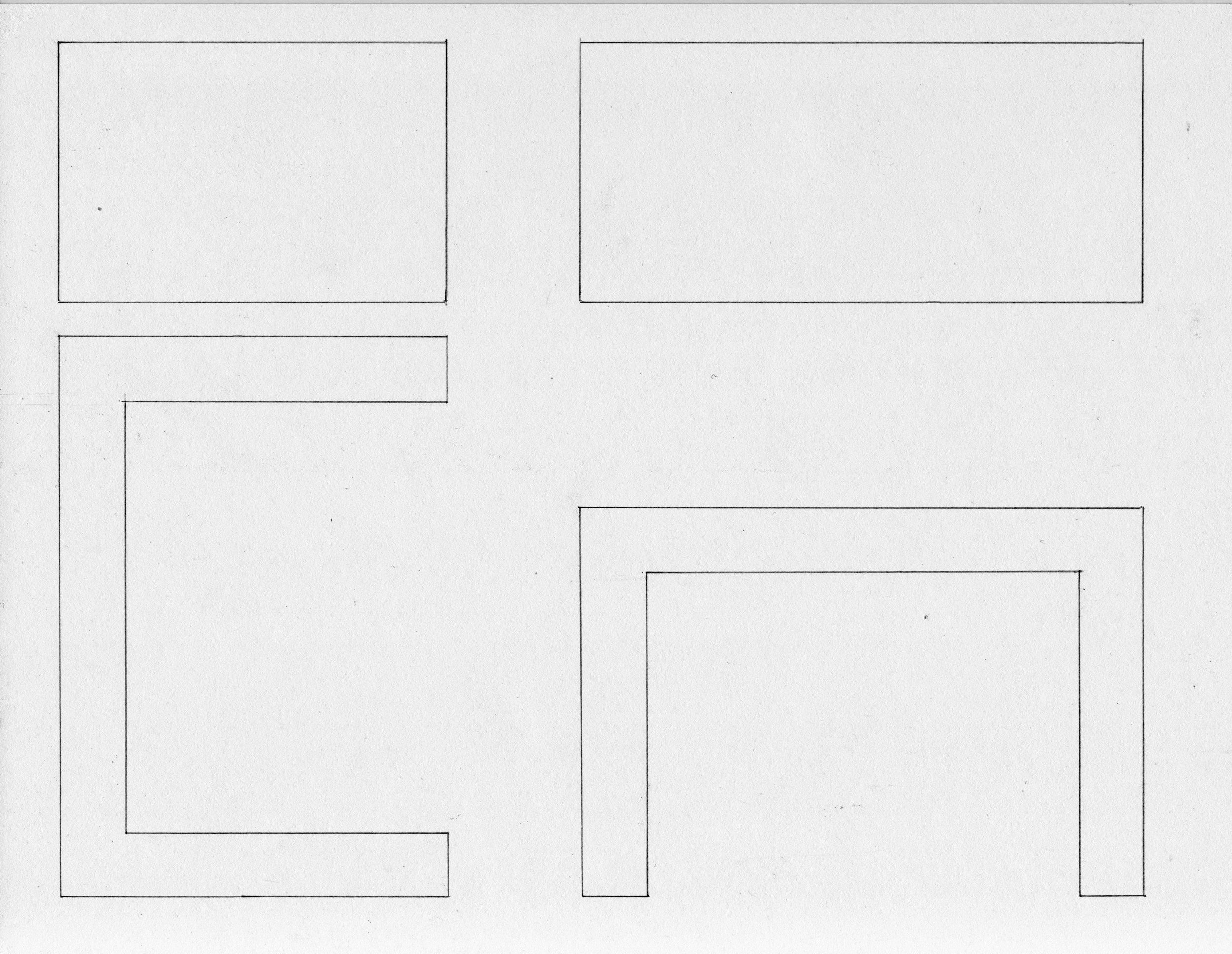

Mission Line Mirror

Let’s reflect for a moment on moving house. Mathematically speaking, moving is a binary equation. One night you are sleeping at your old address, and the next you and your belongings are someplace new. Moving-in is more of an asymptotic function; at least it always has been for us. Prior to occupying our mid-century ranch in late 2019 we took the opportunity to repaint all of the walls and give a fresh start to the decor. The “moving-in” proceeded along its usual course: put the essentials in place and install the remainders g r a d u a l l y over time. It has been our experience that the last things to move-in are always the wall hangings. This time, low ceilings and plenty of windows served to minimize the available wall space, which in some ways made it easier to live without, but also heightened the impact of every hanging decision. That sets the scene for the latest Project, a new dining room mirror.

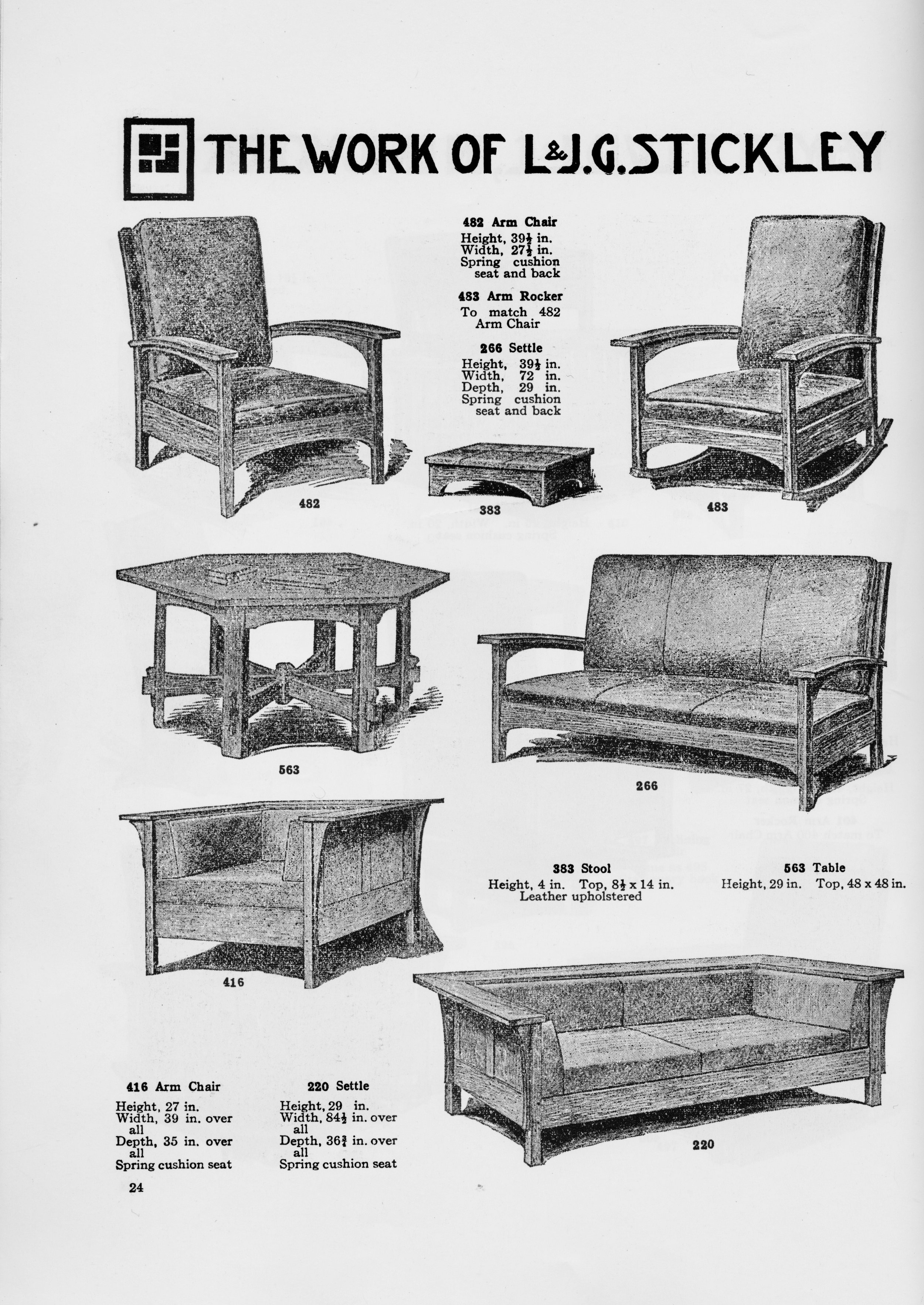

Like many households, we have always had a mirror in our dining room. I think its purpose is to make the space appear larger, but it also adds vitality to the setting and comes in handy for that occasional self-check. A previous renovation had opened up our current dining “room”, yet the space still called for a mirror. However, real estate on the lone remaining wall was too limiting for anything we had in stock and so this potential hanging took its place with the others along that asymptote to infinity. And then I noticed an example of a Craftsman style mirror while reading a book on the Stickley’s. This L. & J.G. Stickley mirror had exactly what was needed: substantial width and narrow height. It also appeared alluringly proper. At the time (1905), Leopold and John George declared that their “furniture was neither Arts & Crafts nor Mission, but ‘simple furniture on mission lines’.”* While clumsy, that expression, likely an attempt to re-characterize the Craftsman™ designs they had blatantly copied from their older brother Gustav’s catalog, still resonated with me.

simple, “mission line” mirror

reproduced from: * Clark, M.; Thomas-Clark, J. The Stickley Brothers; Gibbs Smith: Utah, 2002; p. 135.

Design & Materials

There is nothing special about the design of this mirror, except that prior to discovering it I don’t think I would ever have thought to make one so long and narrow, which I guess does make it courageous in a way. I could not find any measurements for the original but did my best to keep the proportions of frame to mirror (calipered from the photograph) while accommodating the wall’s constraints: approximately 45 in. long and 16 3/4 in. high. The frame would be 2 3/8 in. wide on all sides. As to construction, the joints of the original were most likely mortice and tenoned, but a half lap joint would also work and that’s how I decided to put the 4 frame members together. That’s everything. With the dimensions and joint type settled there was no need for a paper plan. Three board feet of 4/4 quarter sawn white oak, some picture hanging hardware and, of course, the mirror glass were all of the materials required. Simple.

Mirror material

Dimensioning & Assembly

The dimensioning step was pretty simple, too. First, the board was cut crosswise into three sections from which the 2 3/8 in. wide frame pieces were ripped at the table saw. These were then jointed square and thickness planed to uniformity. The four pieces were then chopped to the final lengths and half laps cut on all ends using a dado blade and cross-cut sled. A rabbet for holding the mirror glass was ripped along an interior side of both of the long members and, finally, a couple 1/2 in. diameter oak dowels were prepared by hammering scraps through a dowel plate. These would be used to eventually peg the joints.

Mirror parts

All surfaces were card scraped to remove mill marks and then assigned their positions. Glue-up was easy; simply a matter of clamping all the seams together and double-checking that everything remained square.

Mirror frame assembled.

Just a few steps to go. I wanted to peg the half lap joints squarely in their center and so a simple jig was constructed from scrap wood to reproducibly mark that spot at all four corners. Once drilled, gluey dowels were tapped into the holes and then sawn flush upon drying. The dowel end-grain was further shaved level with a block plane and then the entire frame was sanded smooth using an orbital sander.

The end grain portion of the half lap joints protruded slightly at all corners and so these were shaved flat with a block plane. To give the frame an inviting look, all of the sharp edges were then “knocked-down” using a spokeshave and sandpaper while the corners rounded slightly with a rasp. Then the entire piece was hand sanded using 180 SandNet.

Finally, I needed to make two short rabbets along the backside of the vertical members to complete the housing for the mirror glass. This was done carefully with a router and chisel so as not to ruin the nearly completed piece. I also chose to install the mounting hardware at this stage and then “test hang” the empty, unfinished frame on the wall. This allowed me to get everything straight without having to handle a heavy mirror in the process.

Finish

To fit with the existing furnishings I wanted the oak frame to be darker than the typical, ammonia fumed Craftsman finish. Indeed, all of the Stickley companies employed a range of finishes that they would use to suit the individual buyer or decorating trends of the time. I was aiming for something akin to their “Centennial” finish and followed the 4-step Jewitt process: dye (dark mission brown)/seal/glaze with gel stain (Java)/varnish.

With my part complete, I sought the services of a local glass shop, Northeast Glass Works, to supply and mount the mirror glass into the frame. They did a great job and we now have a mission line mirror to complete our wall.

Mirror on the wall

No. 220: the finish!

In the fifth installment we (at last!) find ourselves approaching the finish line for the No. 220 Prairie Settle, a version of L. & J.G. Stickley’s 1912 home furnishing masterpiece. Only three jobs remained: some carpentry to create the seat; upholstery for comfort; and finishing to complete the “look”. Aspects of these jobs were conducted throughout the build but are summarized now in this final post.

Job 1: Carpentry

Carpentry on this Project is used in support of the upholstered seats, so let’s begin there. Both cushioned seats (as in the catalog original) and inset seats (like many of the other settles from that time) have been used by modern builders and restorers of the No. 220. This posed the first of many choices to be made. Inset seats give a “cleaner” look but cushions are said to be more comfortable, and since we intended to use this piece every day cushions were selected. That decision then determines the type of underlying frame to be used by the upholsterers. The cushions would rest on a platform that, itself, would rest on a hardwood cleat built around the inside of the frame - all out of sight, in the end. After consultation with the upholsterer (more on him later) the dimensions for the cleat and frame were decided and good old fashioned carpentry was used for their construction. The cleats were made of hard maple (1 x 1 1/2 in.) and attached to the rails, at the proper height, with glue and screws. A center brace of the same dimension was also incorporated using a half-lap joint to tie it all together. Solid.

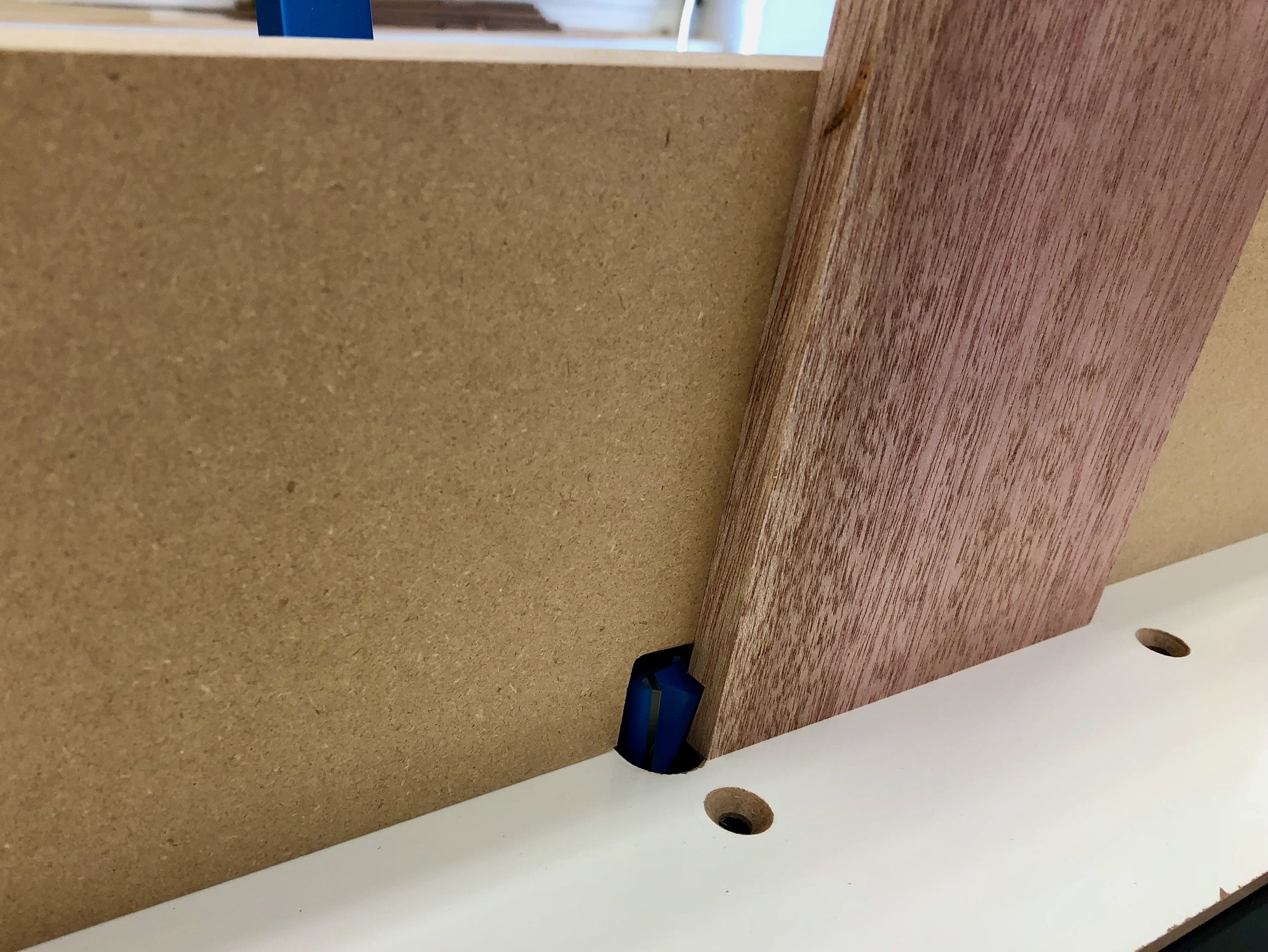

Maple cleats affixed

Next, a platform frame was constructed of 3 x 3/4 in. poplar boards. This ”figure 8” frame would rest on the cleats and sit 1/2 inch below the top of the rails; the two open areas would be filled with stretched webbing by the upholsterer. I used pocket screw joinery to make the frame. Prior to assembly, the corners were notched to accommodate the settle’s legs and, afterwards, all of the edges were chamfered lightly using a spokeshave.

Poplar frame in place

(what’s wrong* with this picture?)

*(In the interest of full disclosure … about a month after the above picture was taken, after surrendering the platform to the upholstery shop, and after attaching the overhanging arms to the frame I realized that I would now no longer be able to drop this platform into position. To remedy this situation, the webbed frame was reclaimed from the upholsterer, one edge was trimmed back to allow for fit, and then the platform was returned to the upholstery shop so that it could be completed. An extra cleat was “sistered” onto the existing frame structure to support the shortened platform and all was well again. Somewhere Henry Ford is chuckling.)

Job 2: Upholstery

Never having attempted the craft of upholstery I was not about to try it here. Instead, I found a local shop, Marcoux Upholstery, with an excellent reputation that was upheld by my every interaction with them on the No. 220 - mighty fine folk. Leather was selected as the covering material which comes with a whole host of decisions to be made concerning source, grade, embossing and color. Most of these choices are based on personal taste & pocketbook, but the surrounding decor and frame wood influence the color decision. So before we could select a leather color we needed to lock-in a frame color. The brown/wine leather sofa we are replacing goes well with the underlying rug and remaining furniture pieces, and so a leather of this general hue was considered a safe choice. That hue required a complementary wood color. Knowing that there is not a single “correct” color for the wood, I chose not to create too many choices. I also planned to use the Jeff Jewitt process to finish quarter sawn oak that employs modern day materials to match the look of aged, ammonia fumed finishes used in the day. Many color variations are possible with Jewitt’s method, depending on the dye and accenting stain used. To create my spectrum of choices I sampled both a “blank” and three different TransTint dye colors on scrap boards: reddish brown; medium brown; brown mahogany.

Dyed white oak scraps + blank

Following this I conducted the rest of the sequence using antique walnut gel stain on them all. In my mind, every one of the dyes samples could work but, to be critical, perhaps the red was too red and the brown too brown for this piece. The brown mahogany-based finish was the winner for us (but I repeated this one on a larger board, just to be sure).

The chosen finish (far right)

That was easy compared to selecting the leather. I won’t go into all of the details but there are a lot of leather options out there. Again, I’m sure that many of these would work just fine for us, and so following a single elimination beauty contest we hoped that “walnut” in the “reagent” embossed pattern would be one of them.

The winning leather

The rest of this job was in the hands’ of Marcoux. They came with their van to pick-up the unfinished, armless frame and took it back to their shop for measurements. A week later they brought the frame back so that I could work on the arms and finish, and then a couple weeks following that the cushions and webbed platform were delivered. I cannot tell you how pleased I was with their craftsmanship - it all looked great.

Job 3: The Finish

At last the final job, finishing the wood. I took my time here, trying my best to make the wood look its finest. A piece this big will always have a few “trouble” spots, but in the whole I wanted the color to be uniform, the grain patterns to be noticeable and the rays to shine - but not too brightly. Here is how the job proceeded.

1. Raise the grain before a final sanding

Since I will be coloring the wood with a water-based dye I needed to first raise the grain with distilled water and then remove the resulting fuzzy nubs by sanding. I used a piece of 180 grit SandNet on a sanding block for the job. This preliminary step ensures a smoother surface and even coloration.

2. Dye the wood

The TranTint dye (brown mahogany) was mixed at a concentration of 3/4 tsp. per one cup of distilled water and a small cosmetic sponge wrapped in a T-shirt rag was used to wipe it on. An artist’s paint brush was employed to get dye into all of the internal crannies (looking at YOU, corbels). Once the first application was dry the wood was lightly smoothed using 320 grit sandpaper and then a second helping of dye was applied.

Brown Mahogany dye applied

3. Oil the wood

Treating with boiled linseed oil (BLO) is not a part of the conventional Jewitt finish, but I saw a woman post this modification online in describing some Mission-style cabinets she was making and they looked gorgeous. I’m not sure how much this will be noticed in the end, but I thought I would throw it in. Thus, BLO was applied liberally by rag and then the excess was wiped off after 10 minutes. The piece was left to cure for 2 days.

Boiled linseed oil applied

4. Seal the wood

Even with a coat of BLO I wanted to be sure the wood was sealed prior to the next staining step. For this I used a coat of General Finishes Seal-A-Cell product, applied by rag and cured for 24 hours before smoothing lightly with a maroon Scotch Brite pad (synthetic steel wool).

5. Stain the pores

The object of this step is to highlight the unique pore and grain structure of oak. It will also darken the entire surface a bit to produce the final color. This so-called “glazing” step is the signature component of Jewitt’s finishing method. I applied a dark brown, oil-based gel stain from General Finishes (antique walnut) with a rag, rubbing it into the cavities with a circular motion and then wiping away the excess in the direction of the grain. The stain was left to dry for 2 days before giving it a cloth rub-down. While not conveyed well by these photos, each step has served to color the wood, deepen the texture and highlight the contrasting grain patterns.

Seal and glaze applied

6. Finish with varnish

This final step both livens-up the color and provides some physical protection from stains and liquids, but this finish is meant to be invisible and so a non-gloss product is called for. I used General Finishes ArmRSeal wiping varnish, satin sheen. The finish was applied with a rag, lightly, in two coats over two days and with an intervening smoothing rub using a gray Scotch Brite pad. Once it was all dry the piece was wiped vigorously with a cloth diaper to even the sheen. Voila!

Complete at last, this latest version of the No. 220 was hauled (carefully) from the workshop to the living room, dressed with the leather cushions and put into service. An epic build for me and a nice heirloom for the family to enjoy.

No. 220: the arms

Really? An entire post dedicated to the arms of a furniture piece? Yes. Remember, these are not just any arms.

The No. 220 Prairie Settle from L. & J.G. Stickley was a breakthrough design in 1912 largely because of its arms. On first sight, the size and elevation of No. 220’s wrap around arms command your response to the entire piece. The accompanying corbels and panels, the upholstery, the finish, they all do their part; but those unique arms are why we gasp. Here’s how they are made.

Materials

There are only two components here, both made from quarter sawn white oak. The supporting corbels will be made from the same 4/4 boards as the stiles and rails of the frame. The arms were to be the same thickness, but their 7 3/4 in. width was larger in that dimension than any of the 4/4 boards available at the lumber yard. It would not do to create this span by piecing together two smaller boards and so I sorted through the wider members of their 4/4 S3S (surfaced 3 sides) stock. These are nice boards, pre-planed and so you know the exact grain and ray pattern as you make your selections. Many were 8+ inches in width, however, their 3/4 inch depth meant that they were 1/16 of an inch too thin for what the plans called for, and that’s before I did any final smoothing in the shop. I ended up selecting these. It’s not the end of the world - structure and function will be fine - just a slight alteration to the intended look that I convinced myself would not be noticed by anyone but me (and now, you).

Arm boards

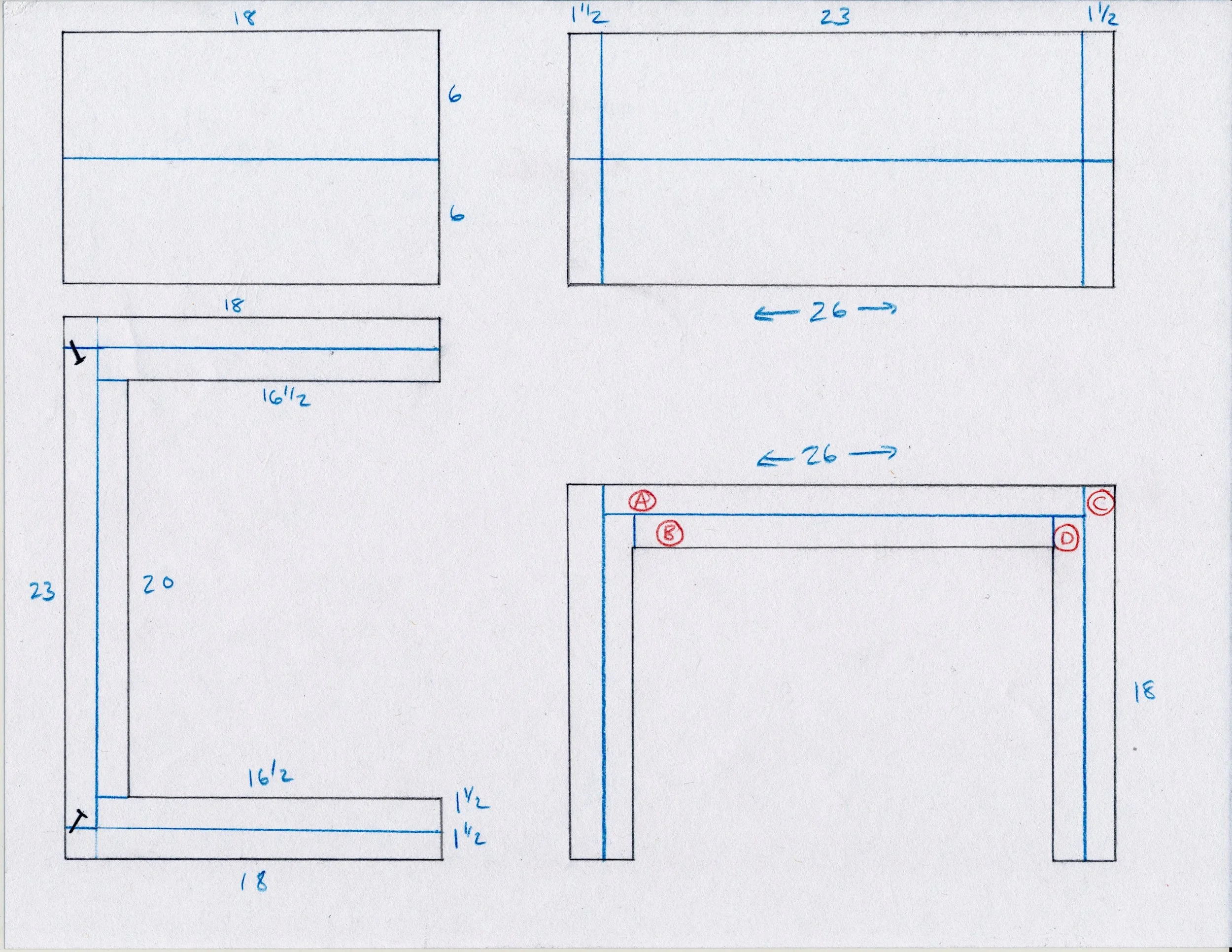

Job 1: Corbels

Corbel is an architectural term describing any projection that juts from a wall to support the weight of an element above it. The arms of No. 220 are supported by the settle’s frame with assistance from seven such corbels spread along the perimeter. Though eye-appealing, these members serve an important function or else they would not belong on a Craftsman design. The plan calls for six corbels of identical dimensions and a seventh, slightly larger one, placed along the center of the paneled back side. I sketched the designs free-hand on card paper after examining pictures of authentic examples (which, again, differed somewhat from the published plans).

Corbel profiles sketched on paper

The larger template was traced onto 1/2 inch mdf board stock and the paper was then trimmed back to the smaller template which was also traced. Next, the mdf template versions were cut-out at the bandsaw and the curves shaped smooth “to the line” using a drum sanding bit on the drill press. These two new “patterns” were then used to trace their shapes (1 large, 6 small) onto prepped white oak boards and the shapes were cut-out at the bandsaw as before. I tried to stay about 1/16th of an inch outside the lines during these cuts.

Cutting out the corbels, two per board

Next, the wood needed to be cleaned-up. A card scraper and 150 grit sandpaper were used to smooth the flat surfaces, whereas, the “cut” edges would be shaved to the line using a flush trimming bit at the router table. In this operation, the mdf patterns made earlier would serve as guides for the roller bearing to ensure that all curves ended up exactly matching the originals. I glued a couple of lips to the mdf patterns that allowed these to be temporarily affixed with screws to the corbel about to be shaped. Worked out well … except that on a couple occasions that little flare near the bottom was, unfortunately, clipped-off in the process. Tear-out like this is sometimes hard to avoid, and the quarter sawn grain orientation only made things easier to rip away. No problem, I just penciled a shallower “upturn” on these two defectives and then drum sanded to the line on the drill press. They say much of woodworking is actually “correcting mistakes”. These’ll look just fine.

Shaping the corbels to pattern with a flush trimming router bit.

All that remained was to create tongues along the back edges for these parts to mount within the previously grooved legs and central stile. This was done using the dado blade on the table saw. Following a final trimming for fit, the corbels were ready for assembly.

No. 220 corbels

Job 2: Arms

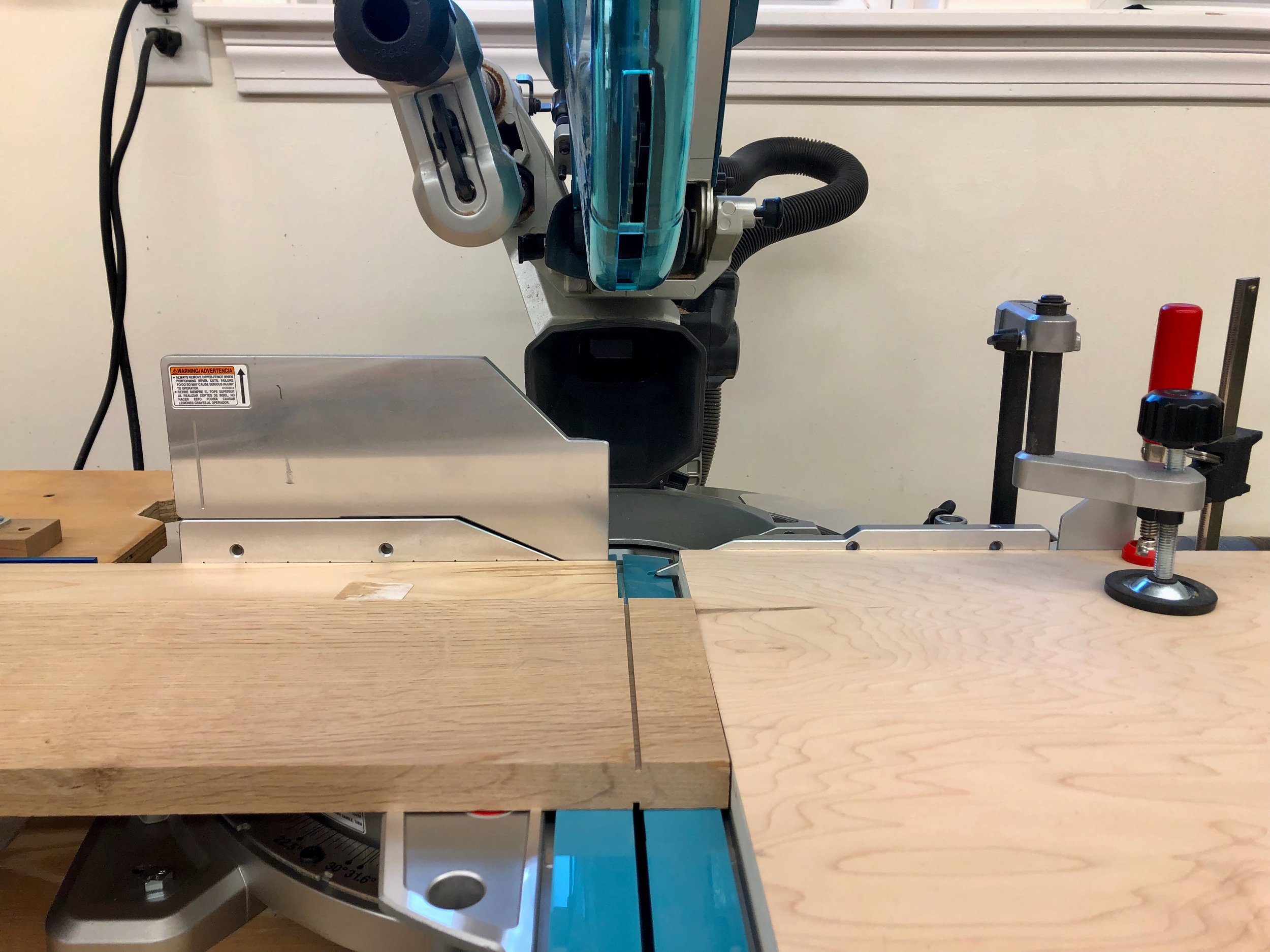

These should be easy. The final dimensions are all in hand: the arm lengths are determined by the as-built frame dimensions; and the 7 3/4 inch arm widths were prescribed by the plan. It all comes down to the order of operations and execution of tactics; in short, properly sawing the four 45 degree angle miter cuts. The goal here is to have a uniform looking seam, and one that is as tight as possible. My strategy was to cut one end of the back, say the “right-hand” side, and the corresponding right arm and try to get that joint “correct” before tackling the other side. That way, if a recut is needed, I would still have length to play with along the back. Should everything go as intended each of the corner angles sum to 90, but any deviation from 45 degrees in this first cut would need to be compensated for in the second if both the 90 degree angle and a tight & true seam are to be formed. I’m not sure why this situation bothered me so much before any cutting occurred, maybe its just the scale of things (an 11 inch hypotenuse!). Anyway, because of that scale I decided that the sliding miter saw was the machine to use for making the cuts.

To get started, the board stock was ripped to the correct width and the edges jointed square. Things are too cramped in the workshop to wield a 7 foot board at the jointer and so an antique No. 7 Stanley jointer plane, once belonging to my great-grandfather, was used to square the edges. Andrew restored this beauty a few years ago and it provides smooth & faithful service whenever called upon.

100+ year-old Stanley No. 7 plane and arm board

Time to do some cutting. The first miter was sawn on the back arm and then things got hairy. Not only was it not the perfect 45 degree angle set at the sliding miter saw, the cut, itself, was a bit “hollowed-out” in the center. What’s going on here?!

Cutting the back arm miter

I cut the second board and, again, things were just not right. While these were not fatal imperfections they would need to be fixed before joining. Maybe I should have paused at this point and just switched to using a track saw, but instead I took the route of fashioning a shooting board to correct the situation. Shooting boards are handy shop jigs that are easy to construct. They are used to guide a hand plane tilted on edge to cut along end-grain wood and I always thought I might need one to smooth the sawn edges before joining - only now it was required to also rescue the integrity of the angle, itself. Most 45 degree angled shooting boards are rather small, used primarily to shave the ends of picture frame stock. The challenge in this case was making a shooting board that could accommodate an 11 inch “shave” at the end of a 7 foot board. The typical design was a non-starter for this scale, but the key mechanical features could be preserved in a temporary set-up constructed from a few oak boards, screwed together and then clamped to the surface of my workbench (see below).

Shooting “board” set-up, in use

This “jig” worked surprisingly well. With a re-sharpened plane iron and some patience the skewed quarter sawn end grain was brought back to a flat 45. Not knowing the cause of the original error, I proceeded as planned: cutting at the sliding saw and beautifying that result as best I could at the shooting board until both of the corner joints passed inspection. I have since discovered a mechanical mis-alignment between the saw’s blade and the sliding arm. The machine is currently undergoing rehabilitation at the local Makita service center. I know, ‘it’s a poor carpenter that blames his tools’ - but they should, at least, meet you halfway!

Assembly

One final modification prior to assembly: biscuit slots. “Biscuits”, mentioned in earlier Projects, are football-shaped wooden wafers that assist glue joinery in two ways: 1. by providing a mechanical alignment between two pieces; and 2. by furnishing face-grain mating surfaces, which is particularly valuable when, as in this case, the joint involves end-grain wood - a notoriously poor glue bonding surface. I cut two biscuit slots into each of the angled ends with my handy biscuit joiner. Glue applied into these slots and unto the faces of the biscuit wafers will furnish a strong bond “within” the joined arm sections. I also cut three such slots into the upper rail and back arm board to ensure proper register here during assembly.

Final assembly of the arms would occur on top of the frame. The main object here was to attach the three arm pieces together, paying particular attention to the mitered seams, and since I needed a flat area to do this, it was either the frame or the floor. Also, since the assembled “U”-shaped arm structure would be rather fragile and unwieldy to handle afterwards, I decided to glue the arms to the frame at the same time. This necessitated mounting the supporting corbels in place too and so the whole thing was glued in a single session with assistance from my son, Ben. It went pretty well. I clamped and glued the long back arm section and its corbels to the frame first. After a 45 minute cure this gave a stable base for attachment of the remaining pieces, and it also allowed me to liberate and re-purpose some clamps - always a limiting resource. Next, the remaining corbels and side arms were glued into place. No drama (whew!).

All parts glued securely in place

The clamps were removed the following day and everything looked as it should. To complete the arms, the surface was sanded lightly with an orbital sander and then all of the sharp edges surrounding the arms were broken using a sanding block. A final hand-sanding over all surfaces (150 grit) made everything smooth and ready for finishing.

Branching Out

Another year under the Red Top and time to reflect on that newly formed ring.

Incremental mass

First, the facts. Along with a few accessories for our home and some items crafted for family & friends, 8 capital “P” Projects were completed during the year (plus, the No. 220 is well on its way). Not a bad year. I’d say the Ledger chest was my favorite piece, followed closely by all the rest. Included in these are a garden structure and a “winged animal” house, the construction of which are now becoming annual traditions.

Those are the quantitative metrics, easily compared year over year. Qualitative metrics also count, and these come from the new techniques and lessons picked-up along the way. For instance, when the year began I had yet to construct my first drawer and now I have made nine. Sliding doors (2), a sliding lid (1), panel edged boards (11) and finger jointed corners (4) were also fashioned for the first time in 2022. Learning new skills is the most rewarding part of the workshop experience for me; that, and capturing the thrill of it all in this forum. Upon reflection, I probably last acquired manual skills during my graduate research days, and then spent the subsequent “working” years applying those in and around the chemistry laboratory. It feels good to again be in a realm where there is room to grow.

New Growth

The Red Top Workshop sits in Harvard, Massachusetts but its roots emanate from the opposite hemisphere. “Asian Inspired Furniture” is the tag line on the website and East Asian furniture design was the inspiration for nearly everything built during my first few years as a woodworker. This theme was continued in 2022 with completion of the Ledger chest (Japan) and Stationery chest (Korea), but a new style has gained my interest based on the Arts and Crafts movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. English Arts and Crafts furniture design, and its American cousins, “mission” and “Craftsman”, produced beautiful furniture that relied on simple construction, meaningful features and robust materials as their raison d'être. Conceived as a response to the overly ornate Victorian styles, Arts and Crafts furniture also happens to share many characteristics with the simple, straight-forward works of Korea and Japan. Previously, I have commented on the genius of Gustav Stickley and the influence of his Craftsman designs on American furniture, and will likely have more to say on the Arts and Crafts pioneers as I continue my research. The aesthetic is so compelling to me that it is sure to populate future work.

In fact, I may need to re-brand so as to include this broader interest into the identity of The Red Top Workshop. That, too, is a satisfying aspect of furniture making; the ability to respond to developing interests by applying previously acquired skills to the creation of new motifs. If you think about it, that’s how a tree shapes itself over time, developing branches where the light is best. And thriving in the process.

Happy New Year!

No. 220: the frame

The framework of most sofas is rarely seen nor thought of. Buried beneath padding and fabric, it performs its supporting role dutifully in the dark. And that’s just as well, for what you would see in the light would be unremarkable materials held together by the occasional wooden joint and various metal fasteners. Not judging. It’s the way frames are built when meant to be covered. The settles of a century ago were different, though. Supported by exoskeletons, there was no place to hide slapdash construction. In fact, their bones defined their being; upholstery was just a pretty gown. Even if Craftsman style is not your taste, you have to admire the honest presence of this furniture.

Gustav Stickley settle (No. 208) with pegged mortice & tenon joinery

The Craftsman, Vol. V, 4 (1904), p.407

The framework on our Project is different from these early examples, but just as forthright. Instead of the typical slat design, panels wrap the exterior of L. & J.G. Stickley’s No. 220 - like the walls of a boardroom. And then there are the arms! Built to serve, the massive arms impart an air of opulence while surrounding you in coffee table comfort. I find them to be both ingenious and beautiful - by design.

L. & J.G. Stickley’s No. 220 settle

reproduced from the online auction site: artnet.com

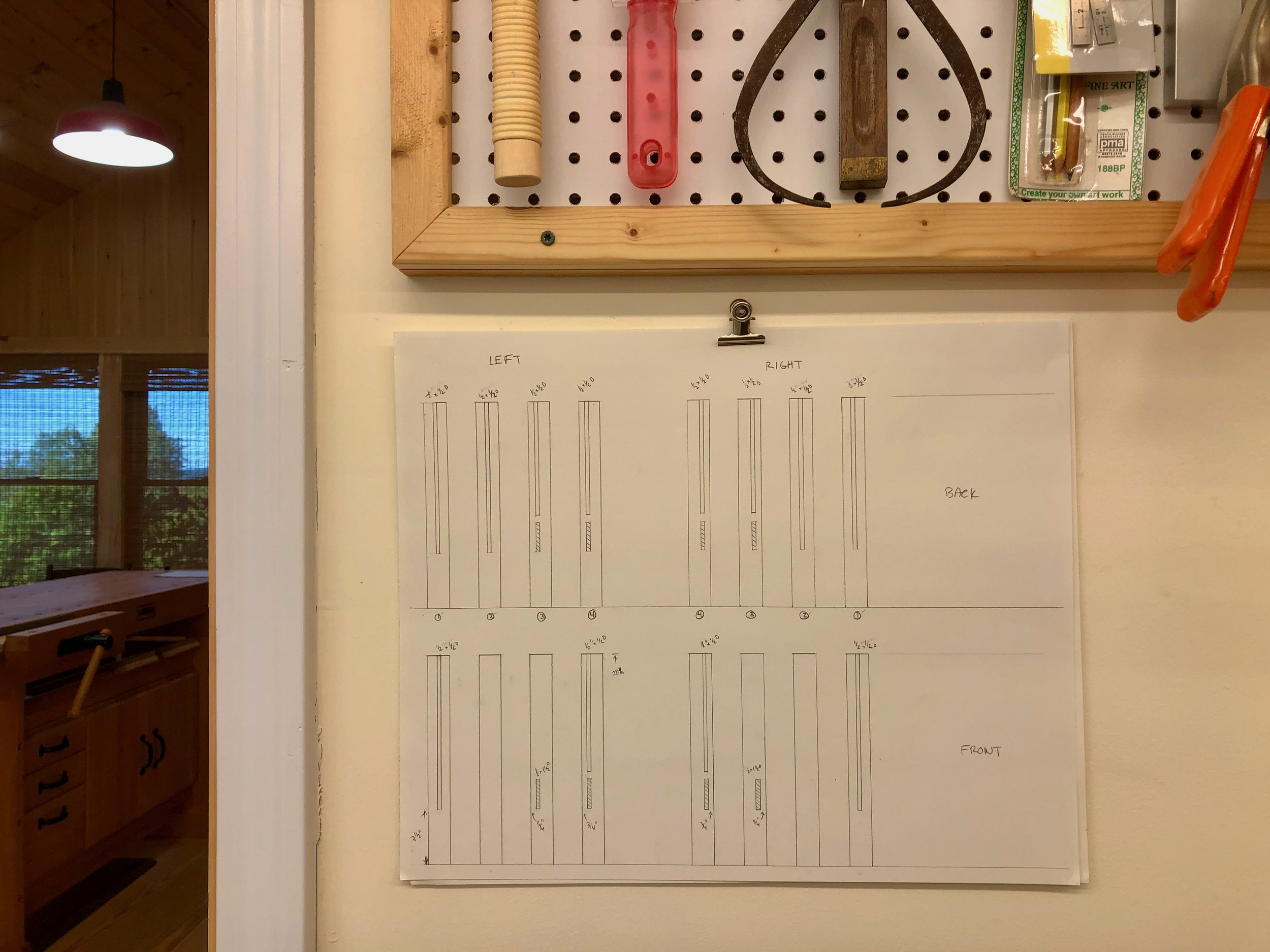

Completing the frame for No. 220 involves routine mortice & tenon and framed panel joinery, the challenge comes from scale. This thing is large; definitely the largest piece of furniture I’ve ever built. So to break the work into manageable portions, construction was approached as a sequence of “jobs” described below.

Job 1: Rails

Framed panel construction, commonly used to make things like doors and dressers, involves 3 components: stiles (the vertical members); rails (the horizontals); and the panels, themselves. Typically the stiles and rails are attached to one another through joinery and glue, while the panels float freely within this construct. In addition to 4 legs, the No. 220 settle contains 13 stiles and 7 rails, all of which will need to be dimensioned and then joined together. These are the joints that create the frame and, as such, should be fashioned with care.

The job begins by prepping the rough 4/4 boards to make them smooth, straight and square. Now, it turns out that a stack of rough lumber “is like a box of chocolates …”. While one can make visual assumptions as to the grain and ray fleck pattern beneath the fuzzy exterior of our quarter sawn oak, it is only when boards are planed that they express their true “flavor”. Generally, a smoothened quarter sawn board reveals something rich and satisfying, but occasionally a fruit-filled one will turn up. (Let’s face it, we all hate when that happens.) Thus, I decided that before I commit stock to becoming stiles, rails & panels I should probably have a taste of every board and then classify them by character. Assuming proper dimensions, the showiest pieces would become panels, and the more modest ones the stiles, rails and corbels. In addition to rays and grain, color and the presence of natural defects (e.g., knots) are also a consideration. Eventually, this wood will be finished with stain and varnish where more visual surprises await, but for now I was content to make the best choices and move on.

As a final obstacle, one of the 75 inch long rails would need to come from a board that was heavily curved along both of its edges In order to charm this snake I utilized a straight piece of maple trim material, found abandoned in my basement by a previous homeowner. This 8 ft. long “guide” was screwed along one edge of the oak board, protruding at least 1/4 in. all along the way. I could then ride that guide along my table saw fence during a rip cut to produce a straight oak edge on the opposite side. Removal of the guide then put this board on par with the rest of my stile & rail stock, which were then all jointed/ripped and chopped to size.

Riding the guide (in white) to straighten a wayward rail at the table saw

Now that the boards have been assigned their role and rough dimensioning achieved it was time to cut tenons on the rails. The bottom rails are a full 6 1/2 inches wide and, though destined to be lost in the wooden crowd, they are the most important members of the frame. Their tenons will fit within the mortices created earlier in the legs. The shorter, side rails need 3/4 in. tenons cut-out on both ends, while the ones on the front and back rails are to be 1 1/2 inch long. As the tenons are centered within the board’s cross-section, the “cut” will consist of making a shallow groove the width of a saw blade on one side, followed by flipping the board over and making the same depth cut on the other. These initial “slits” then define the position of the tenon shoulder. All tenons are approximately 1/2 in. thick and so setting the sliding miter saw blade properly to leave 1/2 in. of material behind is the key step. The tenon length, itself, is easily controlled either during this cut or by a subsequent trim, it is the exposed rail length in between the tenons that matters most.

Making uniform tenon shoulders at the sliding miter saw

The rest of the tenon “cheek” was made by sequentially moving the board 1/8 inch “backwards” and cutting away another kerf’s worth, etc. The bandsaw also works well here for smaller pieces but these big guys are easier to handle prone. The tops and bottoms of the tenons were then cut off using a combination of hand saw for the cross-cut and a band saw to rip the final dimension, a 4 inch tenon on 6 1/2 inch rails.

Four tenoned bottom rails

If the job is done right, coming off of the saw the tenons should be just fatter than their leg sockets, and they were. These were then trimmed with a shoulder plane and chisel until a firm fit in a fully seated joint was achieved.

Next, I took a deeper dive into the published plans and decided to make some changes. For some reason, the plans called for six taller, so-called “outer” stiles to mate with all of the legs, on to which the upper rails would be attached. All of the seven remaining “inner” stiles would then sit in between the upper and lower rails. Hmmm … having the upper and lower rails attached at different points seemed like an odd feature to me and one that might actually make for a weaker structure. Sure enough, examining the photo of an actual antique piece (above) and trying to glimpse these joints in pics available on internet auction sites and Pinterest revealed the “original” joint repertoire to be simpler. Back in the day, the upper rails, like the lower rails, attached directly to the leg pieces. All of the thirteen stiles were the same size and rode in between these rails, visually elegant and strong. Unsure why the published plan would deviate from authenticity, and even though it meant refashioning some already dimensioned boards, this was the way to go. Now back on track, the new upper rails were dimensioned with 3/4 inch tenons on the ends and the leg and rail structure was assembled (dry) to check for fit and to mark the next cuts.

Dry-fitted leg and rail structure

Everything seemed to fit together properly (with barely enough room to maneuver in the bench room once assembled). Prior to disassembly, all of the edges to be grooved for housing panels were marked appropriately so that no mistakes would be made at the saw.

Job 2: Stiles

Next the thirteen stile parts were dimensioned to proper thickness, width and length before conducting the “value addition” steps associated with joinery. First, using a dado blade at the table saw, a 1/2 in. wide tongue, 3/4 in. deep was created along one edge of the six stiles that connect to the legs. These were then cleaned-up and tested for fit. The table saw and fence were then set up to cut 1/4 in. wide dados at 1/2 in. depth. All of the stiles and some of the rail edges would receive a full length dadoed groove that would eventually receive the panels. A few cuts and adjustments were made on a test piece and then, once satisfied with the result, all of the parts were run through the saw in succession.

Cutting grooves in a stile

This operation completed the rail pieces, however, the stiles would still need to have tenons fashioned along their tops and bottoms to ride within the grooved rails. These were also fabricated at the table saw using a wider dado blade, the cross-cut sled and a stop block.

Cutting tenons on a stile

After a bit of clean-up with chisel and shoulder plane a dry fit of the 24 frame parts confirmed that all was on track. This also allowed for final measurement of the panel dimensions.

Framework fit together

Job 3: Panels

I’ll just say it: making panels is an enterprise that seems to take longer than it should. To be sure, there’s a beautiful payoff in the end, but one still has to be in the proper mood for panel-making if the exercise is to be enjoyed. So after cleaning the shop, sharpening some chisels and re-surveying the remaining boards I managed to muster enthusiasm for this next task. To start, you cut the lightly thickness-planed 4/4 boards to rough length and width at the miter and table saws, respectively. You then re-saw them along their narrow dimension into two pieces at the band saw, and finally thickness plane these thinner boards to a uniform 3/8 in. depth. This creates a bunch of panel halves, twenty to be exact. To construct the panels, the “interior” edge of each re-sawn pair is squared-up at the jointer and then, after aligning the grain in a book match orientation, they are glued together and clamped; two at a time given limitations in both clamps and space.

Panels in production

Once the glue has dried the rough rectangles are smoothed with a card scraper and orbital sander (150 grit) and then cut to their ultimate width and length dimensions, again at the table and miter saws. For appearances sake I made sure that the glue seam exactly bisects the finished parts. At this point, and by design, the boards are still too thick to enter their grooves. To achieve a fit all of the edges (n = 40) need to be beveled, thereby creating a “paneled” feature on the interior face. For this I used the table saw panelling jig made a while back during the candle box Project to create 1 inch wide tapers along all sides sufficient to provide a snug fit into the grooved stiles and rails.

Panelling the panels at the table saw

The newly cut perimeters were then smoothed lightly with a card scraper, sorted for their position within the framework and nestled into place. As each individual panel exhibits its own grain & ray “personality”, there is some artistry here in their placement with respect to patterns present on the neighboring rails and panels. Once upholstered, the un-paneled sides of the panels are the only ones that show, and my desire was to frame each of these to their best effect. The “interior” sides have their own uneven beauty, too, revealed during the dry fit.

Dry fit panels in frame

Job 4: Details

Almost ready for the glue-up, but first there are a couple small details to attend. The stiles need to be planed flush with the rails and then labeled for their position during assembly. This was done individually by first identifying any “proud” edges on the end of a stile-rail joint, dismantling that part from the frame, diagnosing the wood grain direction and carefully hand planing away the excess until it tests “flush enough”. The trick is to not plane too deep here as a post-assembly sanding job can accomplish a final smoothing of these joints.

Next, the center stile along the back needed to be grooved to accept a corbel that will support the wrap-around arms. A 1/2 in. wide dado was cut 1/4 of an inch deep into the center of the stile at the table saw. This joint is not mentioned in the plans so I assumed it would be like those that mount the other corbels to the legs. However, I was reluctant to make a groove the full-length of the corbel, and in the process weaken the associated rail members with a cross-cut dado, so I decided to leave the top and bottom rail alone with the intention to use screws from the inside face to further secure the corbel during assembly. This is certainly a departure from authenticity, but an invisible one at least.

Grooved center stile in place

The front rail also needed to be beveled along the top edge so as not to irritate the legs of those seated above. This was accomplished at the table saw, applying an 18 degree angle to the blade and beginning the cut 3/8 in. into the thickness dimension. The rough edge was easily smoothed by hand using a card scraper.

Beveled front rail

Finally, those corner seams about the quadralinear legs needed to be dealt with. Recall, the formation of these pieces left a noticeable gap along many of the edges. I had been puzzling on the best way to remedy this situation when my furniture maker son, Andrew, suggested using a burnisher (the tool otherwise used to fold a cutting edge onto my card scraper) to gently crimp the gap shut. He then proceeded to show me how easy this was to accomplish. The result is a smoothly rounded over edge on all of the legs!

Seamless leg corner and burnisher

Assembly

With all of the jobs complete, it was time to glue the frame together. This meant completely disassembling the dry-fit structure and amassing my collection of long clamps for duty. I started with the Left side sub-assembly. These nine parts were put together with ample glue, clamped tight & square and left standing upright. Four hours later, the clamps were liberated and the process was repeated for the Right side, being sure that everything matched exactly in a mirrored sense. The rail-stile joints were then lightly sanded flush with an orbital sander using 150 grit.

Having completed the sides the final step was to join them together with the Front and Back rails. Of course, this included the remaining stiles and panels where there were a lot of wooden junctions to get right. To begin, the two bottom rails were glued to the sides, creating a free-standing rectangle. The back center stile was then affixed, followed by the two flanking panels, and, from there, assembly proceeded outward in both directions. The stiles were fastened with glue, whereas the panels were tapped-in dry. Gratifyingly, following another such iteration, there remained sufficient space to slot panel nos. 1 and 6 into place. After checking that the stiles were all mounted squarely, the top rail was then tapped down into place. Various pipe and bar clamps were applied as the structure was checked and adjusted for squareness one final time before lockdown. Big job!

Glueing-up the frame

Finishing touch

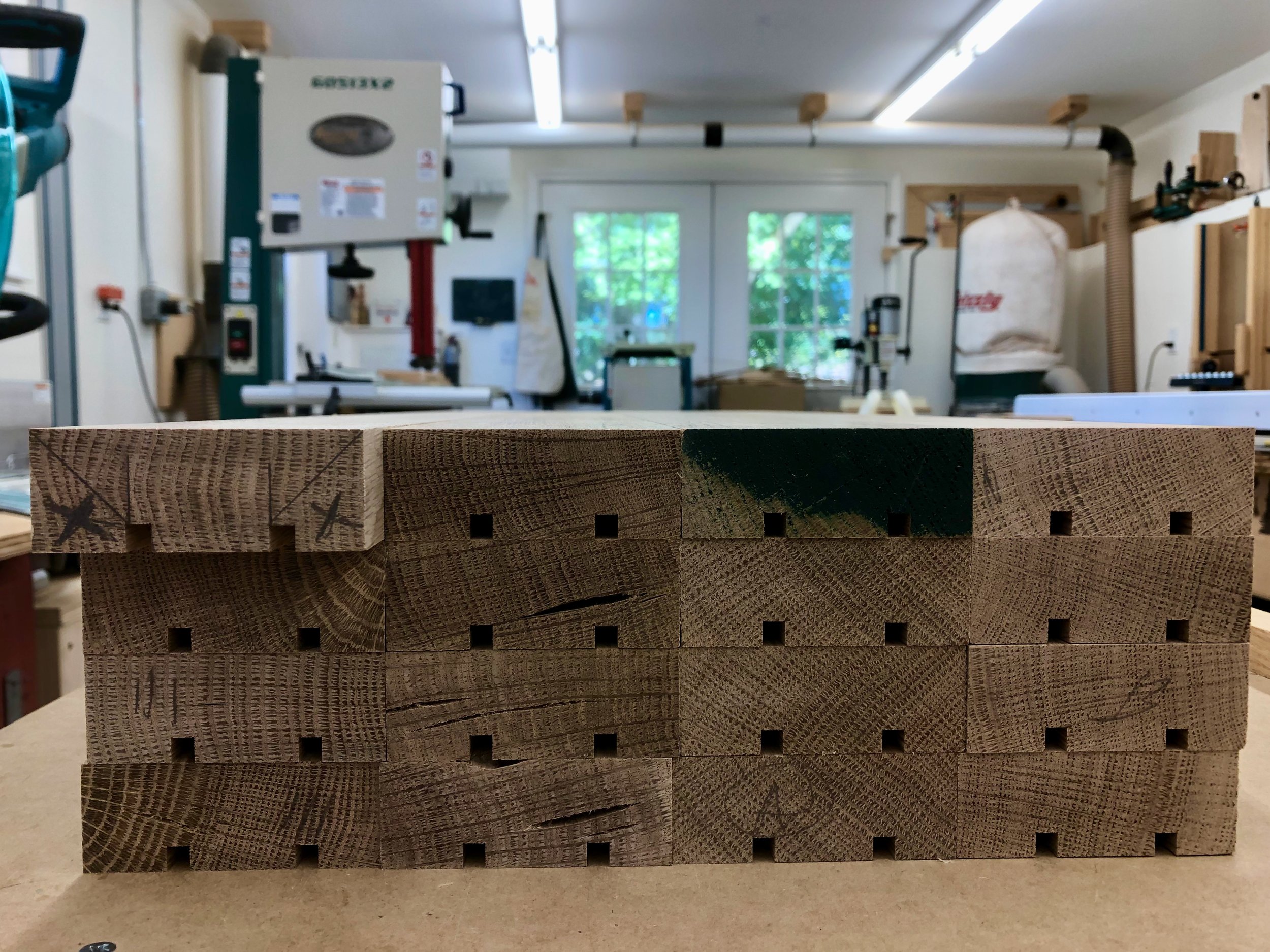

A defining feature of Arts and Crafts furniture is the pegged tenon joint. Adding equal parts strength and character, this element was highlighted by the Stickleys perhaps more than any other maker. The pegs (dowels) in this piece secure the front and back rails to the legs and are shaved flush with the surface once installed. I chose 1/2 inch diameter round dowels for this task, which first needed to be fashioned in the shop.

In the mature craft of woodworking there is at least one tool for every job, and the tool for creating wooden dowels is as simple as they come. A round hole cut neatly into a metal plate is the implement used for dowel-making; that and a hammer. The dowel material comes from a straight-grained, knot-free white oak scrap. This piece was first cut to rough dimensions on the table saw (9/16 x 9/16 x 24 inches) after which the edges were further relieved by shaving with a knife. The resulting irregular-shaped rod was cross-cut into 2.5 inch segments, trimmed further along the exterior with a block plane and then pounded through the circular opening of the “tool” to produce perfectly sized cylindrical dowels. While the act is violent, the result is beautifully Euclidian. Using a pencil sharpener, the penetrating end of each dowel was tapered slightly before use.

Pounding out the pegs

To peg the tenons, two 1/2 inch dia. holes were drilled to a depth of 2 inches at each of the rail-leg joints. I used a hand drill and shop-made jig to keep the holes uniformly positioned and straight. A glue-coated dowel was then tapped firmly into each opening and, once dried, the protruding end was sawn off using a Japanese flush cut saw. Finally, the rough surface was smoothed with a block plane.

Pegged rail joint

At last the frame is done and this brings the Project to a natural pause. Left to be completed are the arms and their support structure, the upholstery and the finish. Well on our way!

The Railing

I like my neck. Sure, it’s developing that middle aged turkey “thing” but I’m for preserving it all the same. For that matter, I’m rather fond of my wrists and pelvis too, but you wouldn’t know it if you saw me slipping and sliding down the path to the workshop last winter. That’s all about to change with the creation of a new railing.

Background

The door to the Red Top Workshop sits maybe 60 feet beyond the steps from our kitchen deck but there is a 6 foot elevation drop over that span, the final 4 feet of descent navigated along a 20 foot long, stepped pathway put in by the former owner. Nice little treacherous walk. In the winter, ice will glaze the granite landing treads at every opportunity and also form a rather slick rink atop the sloping pavered sections in between. I’ve tried salt, sand and chipping with a pick but it is difficult to keep this stretch clean and safe over a New England winter. After a few painful spills I resorted to the use of boot crampons and a walking stick for assistance with traction and balance. The problem is that I am rarely walking that path to the shop empty-handed. Firewood, furniture lumber, coffee mugs; these things don’t get down there by themselves. What I needed was a sturdy anchor to the ground, a railing, to support my frame and cargo during transit. Pretty sure my insurance company would agree.

The winter commute

Design

The plan began, as most plans do, by first ruling things out. I neither wanted nor required a typical split rail-type fence for this short span of walkway; it would be too massive for the task. A black iron porch-type railing would work, I suppose, but that would seem out of place in the understory bird cover that I was also trying to establish here; like an artifact overgrown by jungle. What I desired was a right-sized, simple handrail support that would blend with the setting. It needed to be wooden, of course, and not shy about declaring its function, kinda like Craftsman furniture (wink).

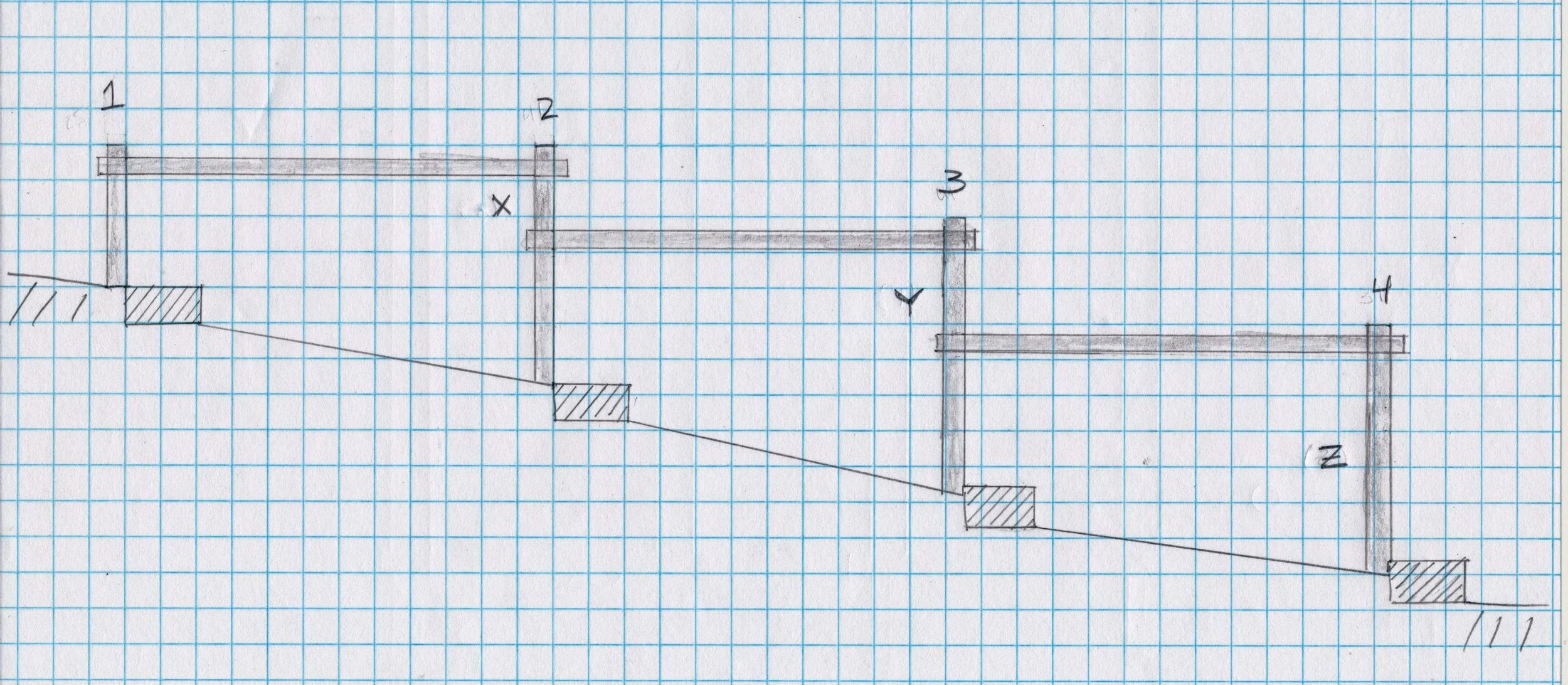

A rough plan meeting these criteria was created on graph paper to verify feasibility and “look”. I decided that the railing should be perpendicular to the posts and not sloped to match the terrain. This might take it out of OSHA compliance but I feel it makes the railing more “fence-like” and naturally prompts a re-grip at each granite lander.

The railing plan

Materials

It turns out that there are very few non-metallic fence materials to choose from at the typical Lumber/Box store. Avoiding split rail pieces and those cumbersome 4x4s I settled on some landscape timbers made from pressure treated yellow pine. These are typically found stacked together on the ground and used as borders but, lumber-wise, I could imagine them to be “live edge” 3x4 inch fence stock. The remaining materials were easy. I would use quick setting concrete for the footings and galvanized carriage bolts to join the members together. Material costs came in just under $100; about the price of an office visit and X-rays, deductible met.

Landscape timbers in lock-down to combat warp prior to construction.

Construction

Structures such as these are made in cooperation with their environment and, as such, ground preparation, rail fabrication and installation would proceed as a loosely-choreographed dance. This adds to the excitement, and if you’ve ever done a garden project you’ll know what I mean.

The un-railed path

While the basic design was set, I still wanted to test some joint options before deciding on the post orientation (i.e., in which direction should the flat sides point?). Detail-wise, I planned to use a cross-lap joint to marry the railings with the posts. This would keep the profile slim and make it all look more purpose-built. That left me with four permutations for how the edges should meet depending on whether the flat or round edge of the post mates with the flat or round rail edge. To decide, I mocked-up the favored option (flat post on flat rail) and then, given the amount of work it took to build this one, assured myself that it was the best and no others need be sampled. The “flat-on-flat” variant would face the flat sides toward the walkway and furnish the more comfortable hand hold, so there’s that too.

Flat on Flat cross-lap joint

The joint was built by making two boundary-defining cuts with the hand saw (1 1/4 in. deep, 4 inches apart) and then chiseling out the interior waste to create a “slot”. This slot was then overlapped with a second such slot to fashion the cross-lapped joint. It was pretty simple work and I think the damp “wonder wood” actually helped with the chiseling step. However, it took a lot of whacks to make a joint, and convinced me that, in addition to the railing cuts, the 6 slots in the posts would also need to be fabricated in the shop prior to installation to keep the chisel pounding from dislodging everything in the ground. Alternate methods for cutting the posts using a router or table saw were vetoed in favor of manual labor, which just felt right.

Chiseling slots in the test joint

Having decided on this method of construction meant I now needed to re-formulate my installation plan. My original vision of cementing all of the posts in place and then cutting-out the railing slots no longer applied. And, while it would be bit more complicated than just sequentially digging/inserting/fastening from one end to the other, that’s basically how the new plan goes. Here are the constants and variables in play. Regardless of their length, all slots on the railings would be created 2 inches in from the ends, likewise, the posts to receive these railings would be slotted 2 inches below their tops. Further, the uphill end of all railings would start at 22 inches above grade. These constants come from the design and keep things simple, trim and uniform. The variables come from the environment and are largely due to the inconsistent drop in elevation between the granite landings. We don’t need to measure this decline, simply accommodate it during construction. In practice this drop determines the position of those niggling second cuts on posts 2 & 3 and height of the cut on post 4, depicted as segments X, Y, Z on the plan (above). A persistent bend in the pathway and non-uniform spacing of the granite blocks contribute the final variables.

Following a few last minute measurements it was time to dig the first hole. I started up top with the shortest post. The plan was to bury each post about 2 feet into the ground and tight to the existing walkway. Down there they would sit on a bed of gravel and be anchored by a concrete surround. A post hole digger did a good job excavating the 10 inch dia. cylindrical cavities, and since the ground consisted of fill dirt I did not have to fight with New England rock.

Digging the first hole

A handy jig was made to assist with mounting the posts. This consisted of a few 2x4s put together in a manner to hold a short section of railing 22 inches above the granite step. Once the bottom of the post was trimmed to length, inserted into the hole and tamped into the gravel bed it could then be held at the proper height by inserting the rail section of the jig into the joint slot. Following instructions written on the fast setting concrete bag some water was then poured into the hole followed by half-filling with concrete powder. At this point the post, held by the jig, was re-leveled on all sides. The hole was then nearly filled with powder and more water poured on top. After a few minutes of soaking, the concrete on top was the consistency of pottery clay and could be tapered with a trowel to shed rain water away from the post. Following a final level check this was then left to cure while the next hole was dug.

First post in place, held in position by the jig

Getting the second post in the ground and the first railing attached to it would complete a “section” and validate the procedure to be used hereon. I’ll describe that process so that afterwards we can fast-forward to the finale.

Hole no. 2 was dug to 24 inches and the jig put in place so that a measurement from the bottom of the hole to the stub rail could be made. This distance determined the position of the first slot on post #2. That slot was cut-out in the workshop, as well as a slot on the end of rail #1. A pilot hole for the first carriage bolt was also drilled into the rail. Next, the post was put back in the hole, leveled and mounted to the jig. Rail #1 was also temporarily installed onto post #1 by completing the drilled pilot hole and sliding a carriage bolt through it. This “dry fit” would allow me to mark the position of the final two slots. Upon leveling the rail and bringing it alongside post #2 I could pencil the intersection on both members, defining the areas to be cut for the joint. (Hope that was clear.) Removal of the temporarily mounted rail and post allowed for chopping the joint slots in the workshop and then cutting the members to final length. Installation was simply a repeat of the dry fit exercise, only with wet concrete thrown in. Worked well!

Dressing concrete upon completion of the first section

The second and third sections were completed in a like manner over the next couple of days. At some point I realized that sawing a relief cut mid way across the 4 inch joint slot made the subsequent chiseling step much easier - enjoyable actually. Always learn!

The newly-railed path

These garden Projects are a reminder that it is fun to get out the heavy tools on occasion. They are a chance to not sweat the final 1/32nd of every inch and still build something solid & useful. Assuming those posts stay put when the ground freezes I think this railing will enhance both the beauty and safety of the workshop path for many years to come.

No. 220: the legs

Prelude: The next few installments will describe the creation of a No. 220 Prairie Settle. Following a brief description of background and preparation this first episode focuses on construction of the leg components.

The allure of Craftsman furniture, regarded as America’s first true furniture form (sorry Shakers), comes from the simplicity of design and material. Graced with very few ornamental detours, the admirer is forced to recognize and then appreciate the form, joinery, wood and finish that, when executed properly, create a beautiful four-part harmony. I love the Craftsman aesthetic and have made a few pieces inspired by that style, as well as some related mission items. In most cases I have either reverse-engineered the plan from a 100-year old picture or created my own design using dimensions and joinery consistent with the style. On my last Project I stuck pretty close to the original published plan and found it a surprisingly absorbing challenge to re-create an antique. I’d like to do the same for the venerable No. 220 settle first made in 1912 by Leopold & John George Stickley, and in this endeavor I am helped enormously by the work of Robert W. Lang.

Robert Lang is a very talented woodworker, magazine editor and author who is also regarded as a specialist in Craftsman furniture. In addition, he manages an incredibly informative website. His latest passion seems to be the drawing program SketchUp which he uses to re-create plans for authentic furniture pieces. In 2013 several of his earlier books were combined into the hefty, Great Book of Shop Drawings for Craftsman Furniture. This masterpiece, since re-issued in hardcover, contains his painstakingly derived plans for many Stickley and related furniture pieces, and among these is the No. 220 settle. I don’t believe I’d have the confidence to tackle this large Project without these plans. Thanks Robert.

No. 220 plan

from: Lang, R.W. Great Book of Shop Drawings for Craftsman Furniture, Revised & Expanded Second Edition Fox Chapel, 2017.

Design

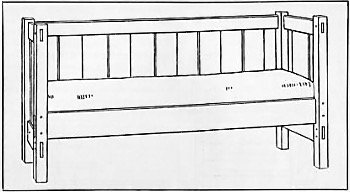

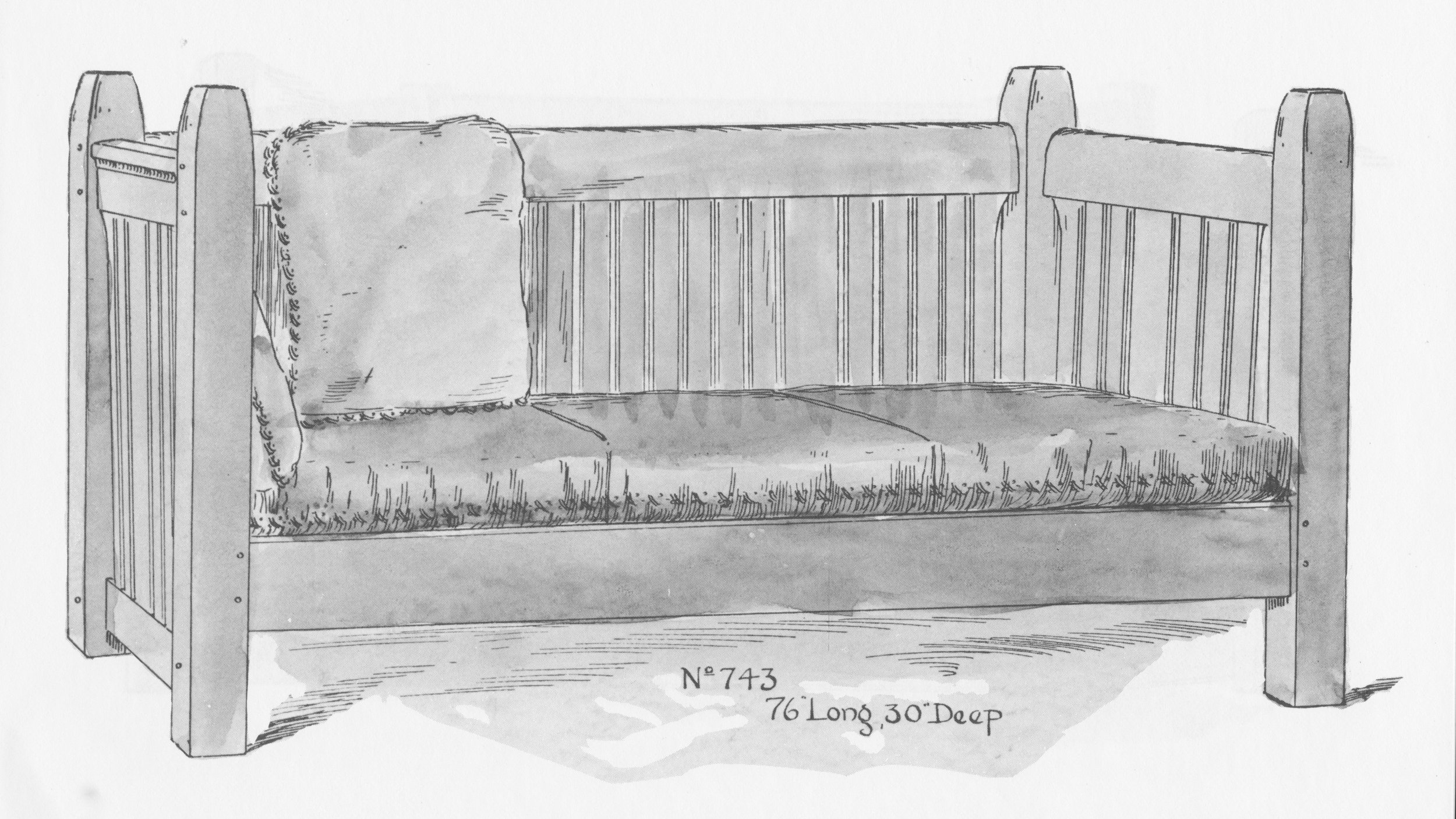

A fair description of early Craftsman settle designs might be ‘four posts, modified appropriately to accommodate the human derriere’. Endearing, yet visually crude by today’s standards, the settle was intended to provide cozy comfort to those who “settled” within its confines in an otherwise drafty room of old.

(example) No. 743 Settle

from: L. & J.G. Stickley, Onondaga Shops Salesman’s Catalog (1906), reprinted in: Early L. & J.G. Stickley Furniture: From Onondaga Shops to Handcraft, Davidoff, D.A. and Zarrow, R.L. Ed., Dover, 1992, p.61.

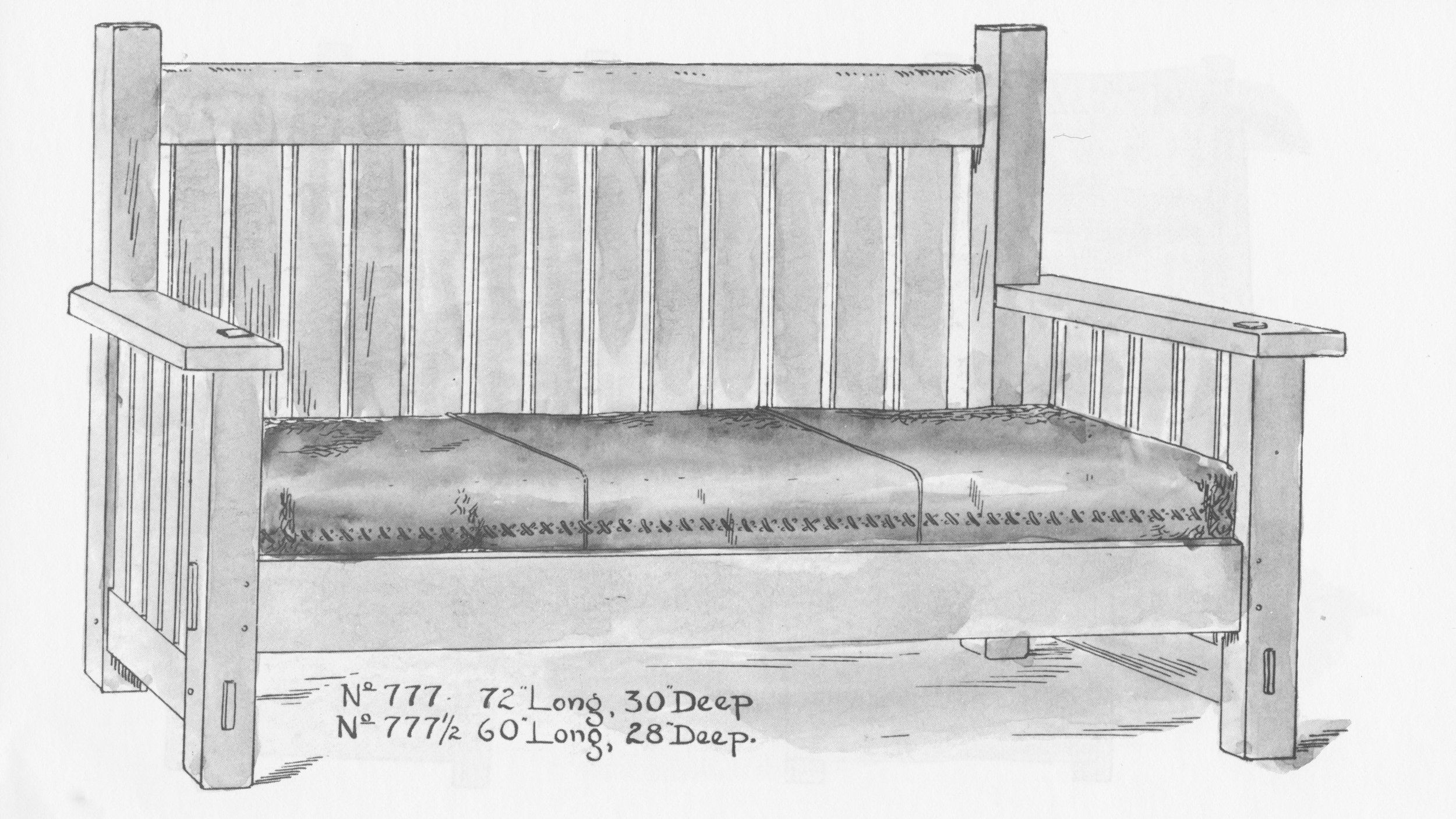

Later versions tended to separate the height of the back from the height of the side “arms”, making something that more resembles the modern sofa.

(example) No. 777 Settle

from: Early L. & J.G. Stickley Furniture, p. 77.

No. 220’s genius was to once again align the back with the arms, but this time at arm’s height, evoking the expansive Prairie sensation. The leg posts are still present to anchor the settle form, but with curvaceous corbels to support the massive arms they are no longer the primary feature.

No. 220 Settle sketch

from: Great Book, p. 150.

Materials

Although the Stickley’s offered some early pieces in a variety of woods (mahogany, chestnut, maple), white oak, quarter sawn at the mill, became the most prevalent wood used for Craftsman furniture. This abundant hardwood was the perfect material for the construction of solid furniture. Due to the orientation of the annular rings, quarter sawn lumber is the most stable form with regard to seasonal movement, and when white oak (Quercus alba) is cut in this manner it reveals the pronounced medullary rays found in this species to create a striking grain figure. Amongst all of the diagrams of quarter sawn lumber to be found in the woodworking literature, I prefer Gustav Stickley’s.

Quarter sawn lumber

Stickley, G. The Craftsman, VIII, 4, 1905, p. 109

I needed a few different dimensions for this Project and spent 2 hours picking through the quarter sawn white oak stacks for the right pieces at my favorite yard, Highland Hardwoods; 76 board-feet in all.

White oak stock

(note medullary rays evident in the center, S3S boards)

Dimensioning