Under the Red Top

making the best of life & woodCoin Chest ep. 2

Picking up on the Coin Chest Project we shift our focus from casework to case components; specifically, six drawers and a pair of doors. Let’s get at it!

Design

Back in October 2025 we left the Coin Chest in a state of arrested development, where all of the chest’s framework parts were complete and assembled, just not glued permanently in place. This was to permit the construction and insertion of a box to house the interior drawers. That box would rest just behind the Chest’s sliding doors, creating an inner chamber common to many tansu of the merchant chest type. The plan was to build a box to fill the cavity, disassemble the surrounding framework, apply glue to the tenons, and then re-assemble the frame with the box enclosed. This may not be the method used 150 years ago in Japan, but it seemed like it would work, today, under the Red Top.

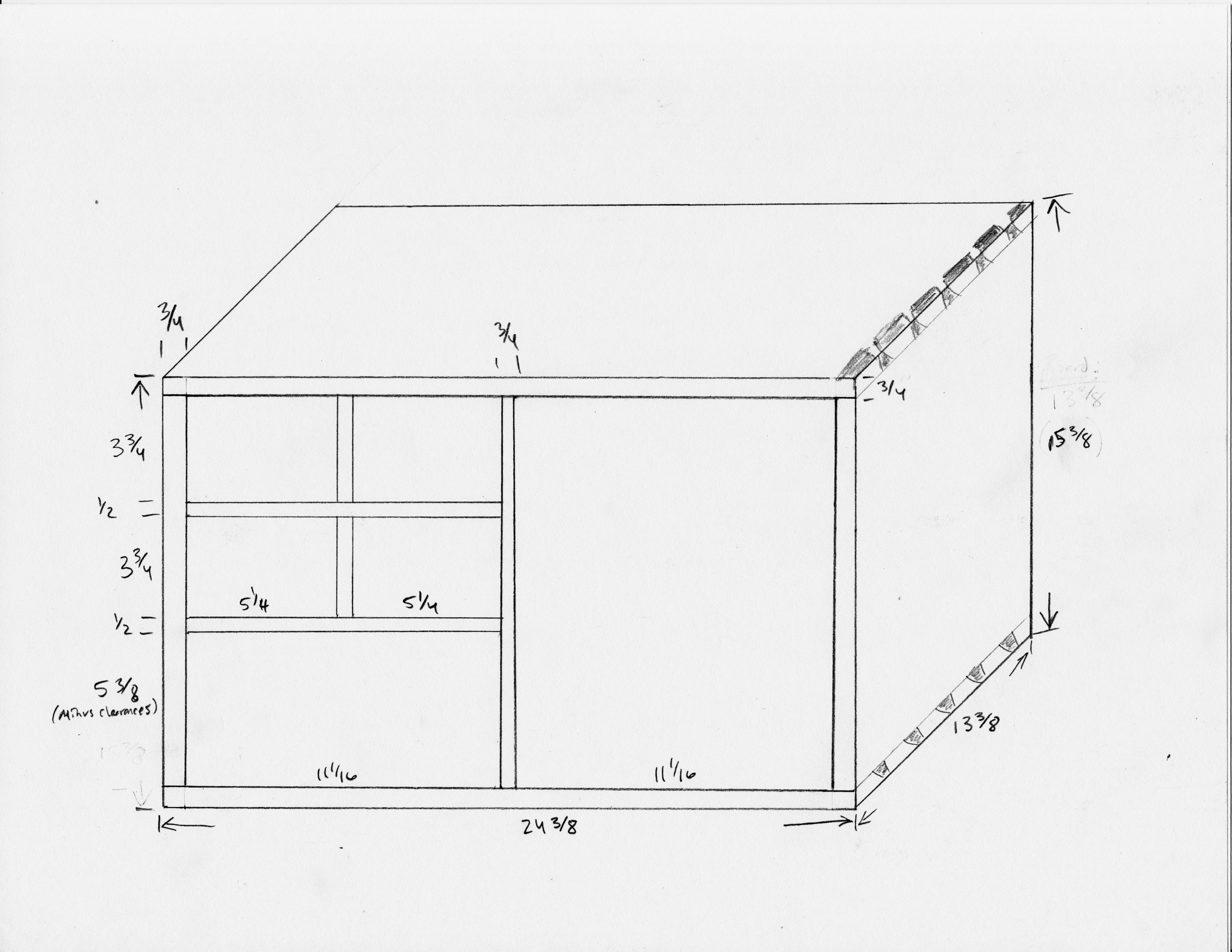

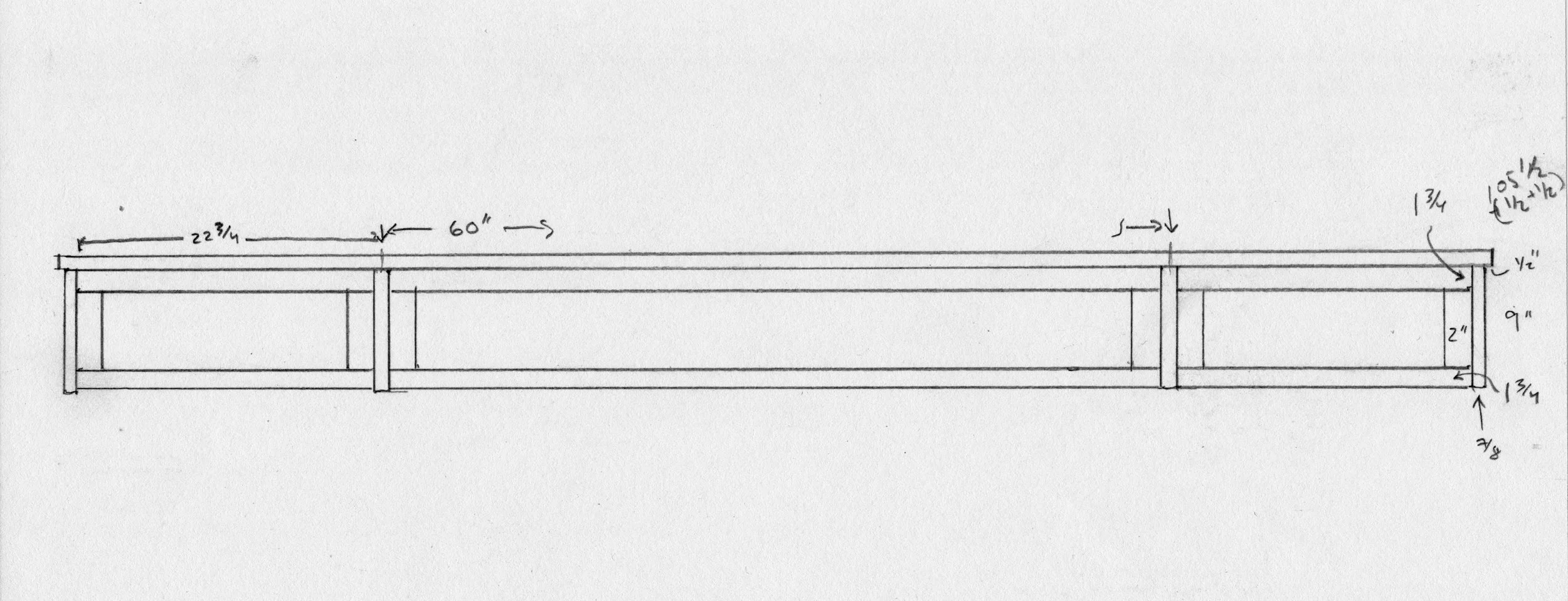

With a construction strategy in place, the final design step was to configure the inner drawers. There is no “right” answer here (alas, there rarely is), but the guiding notion was to create smaller containers that could segregate parts of the collection while keeping things versatile. Only half of the cavity would be “drawered”, the other half would be shelved with the intention to house coin books, magazines and other pieces not fit for life in a drawer. Rough plans for a couple of versions were drawn out and discussed with Mike before landing on the one below. Its construction would involve dovetail joints and dadoed housings.

Coin Chest drawer box

Materials

I chose to make the drawer box out of eastern white pine, a stable, lightweight wood that is easy to dovetail. In the end, only a small portion will be visible. Like the other woods, this was picked out of the fine selection at Reader’s Hardwood Supply.

4/4 Eastern White Pine lumber

Drawer box

The box would be constructed of a top, bottom and two sides - no front or back. All parts would be 13 3/8 inches in width, a dimension most easily obtained by glueing two ~ 6 3/4 in. boards together. The only issue is that I have a 6 inch bed on my jointer and so, to catch that last 3/4 inch, I would need to use my new thickness planer jig to flatten the stock instead. This is an easy work-around that also serves to keep the jointer blades clean. With resinous woods like pine you learn to take the good with the bad: they are soft as a pancake to work, but all your tools get syruped.

Flattening boards on the thickness planer

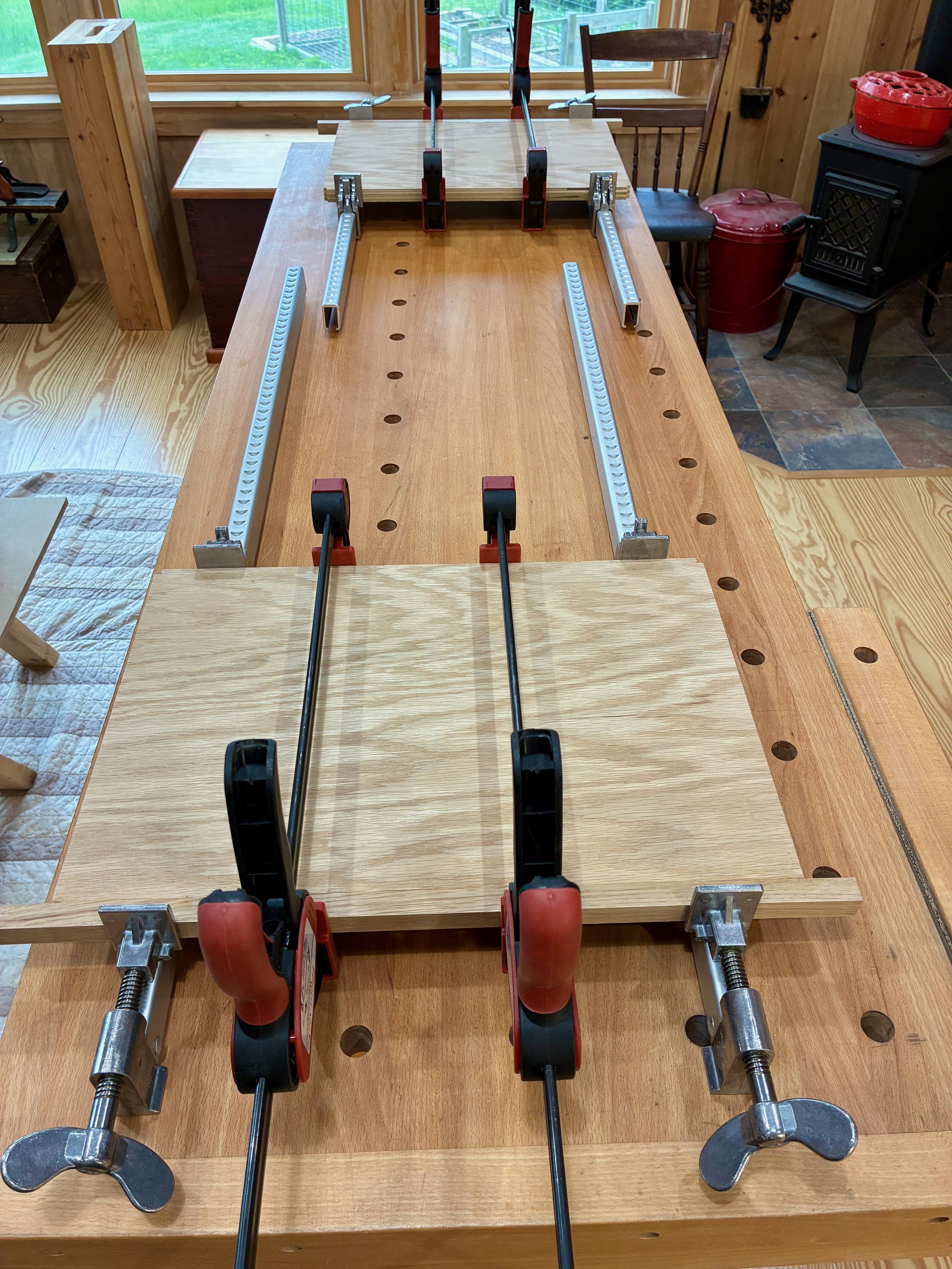

After getting the boards milled to a uniform 3/4 in. thickness, one edge was squared-up at the jointer and then the boards were paired and glued together to make the rough box stock. Once sanded smooth, a track saw was used to square up one end of each board, and then the table saw employed to cut each piece to their final width and length.

Box stock: 4 sides and a central divider

From here the boards were marked, sawn and chiseled in the typical through dovetail sequence. I still consider myself an amateur with this joint, but every bout makes me a better competitor. These turned out pretty nice (in spots). Pity they will be out of sight in the finished piece.

Dry-fit box

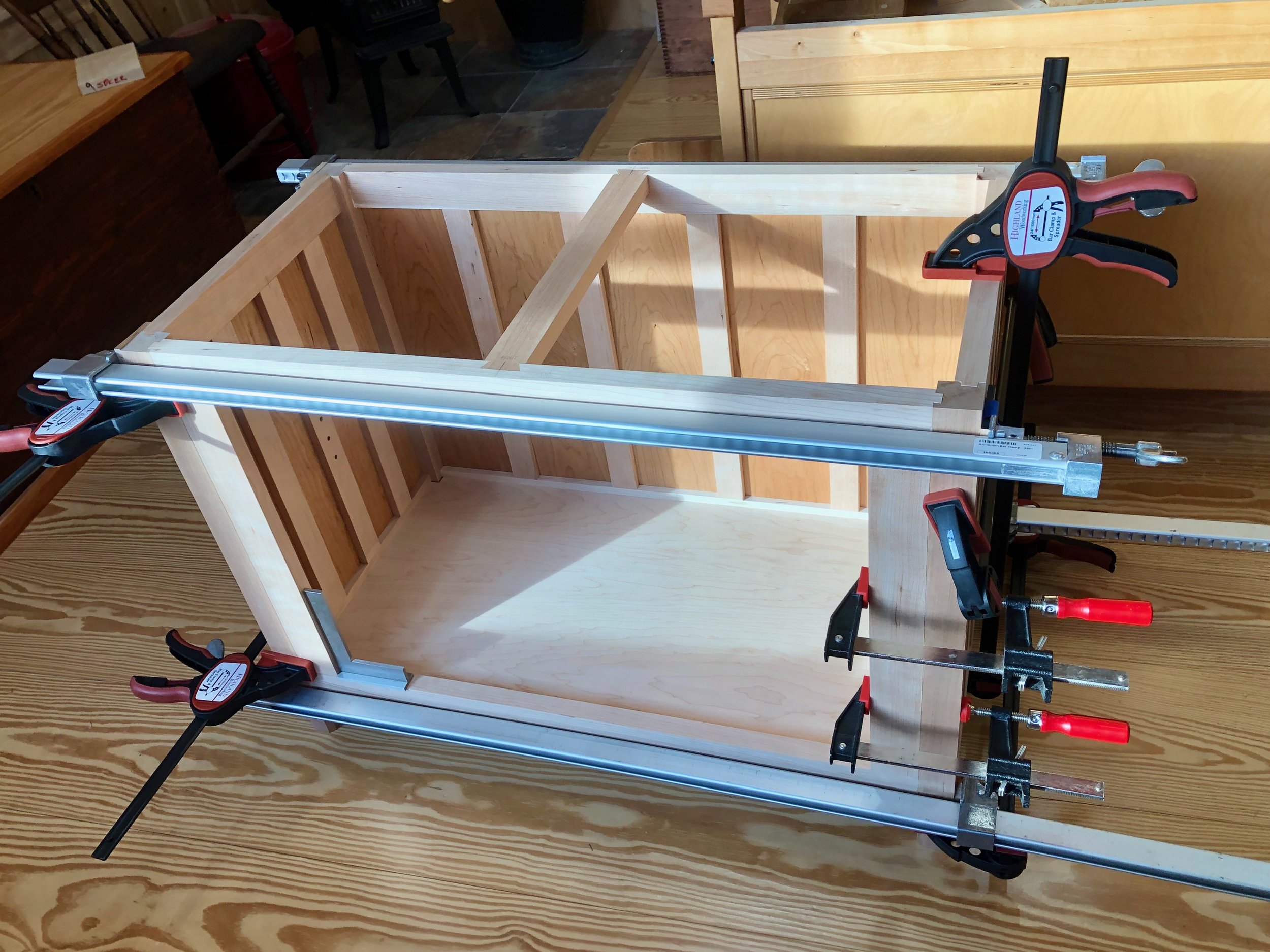

Box completed, I was now able to mark in pencil the position of the dadoed slots that will house the drawer dividers. These were cut at the table saw and then pine partitions were fashioned to fit within the grooves. Some of the partitions, themselves, required dadoes so this was an iterative affair: mark/cut/fit/repeat. Finally, a series of holes were drilled in a couple of the boards to hold the shelf support pegs. During glue-up, the divided box came together without issue.

Glueing-up the box

As designed, the box was still 1/2 inch too wide to fit within the case. You see, I made that box from 3/4 in. boards but, to match the drawer divider widths, I wanted only a 1/2 in. reveal around the edges once situated within the case. Also, tucking the box behind the case framework in this manner assures that no gaps would be seen. To achieve a fit, I therefore had to cut a rabbet along the bottom sides and around the entire back of the box. This was accomplished at the table saw.

Rabbeting the box bottom at the table saw using a zero-clearance sled.

Once all of these modifications were complete, the box fit snug within the dry-fit case. Now, to fill up those cavities with drawers.

Box in a box

Interior Drawers

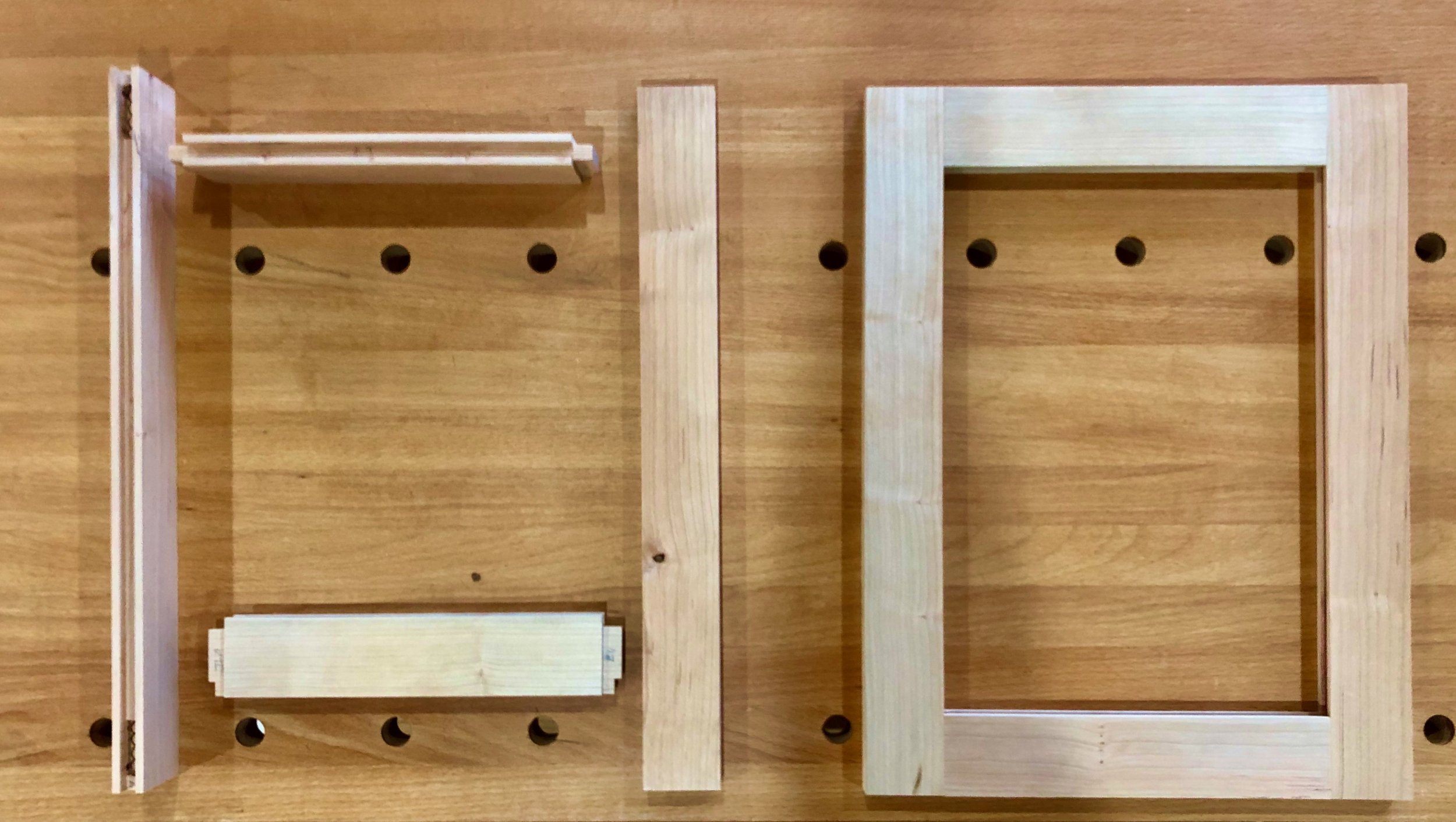

The five interior drawers came next, 4 small, 1 large. These would be made from three woods: red elm for the drawer fronts, poplar for the sides/back, and leftover pine for the drawer bottoms.

Drawer woods, L-R: pine (beneath the box); poplar; and elm

The design for these drawers would be inset, using rabbeted half-dovetail joints in the front and lock corner joints for the rear. But before going too far we had to decide on the drawer hardware. To permit the sliding door in front of the drawer bank to close, any protrusion of the drawer pull hardware would require that either the drawers be recessed into their chambers by that same amount, or the entire box, itself, be recessed within the case. Both of these solutions would make for an unsightly reveal upon opening the sliding door. Thus, flush pulls were chosen to bring both the box and drawers to the fore. Another consideration was color. We wanted the interior hardware to match the black iron tansu hardware planned for out front, and so black, flush drawer pulls were our quarry. This combination does not afford a wide selection but we found one that would work from an eBay vendor in China. I would need to have them in hand before dimensioning the drawer fronts so as to measure, and then accommodate, the drilled socket depth.

While waiting for the pulls to arrive, the drawer sides and backs were prepared. The ~1 in. poplar material was cut to rough width at the table saw, resawn down the spine at the band saw and then thickness planed to 5/16 in. for the sides. The backs were made at 1/2 in. thickness and the drawer fronts were prepped to rough dimensions. I also had time to re-paint a bathroom.

Interior drawer pulls and parts

It turns out that a socket depth of 5/16 in. was required for the pulls, thus the elm drawer fronts were milled “thicker” to 1/2 inch. I used a rift sawn plank for the fronts and kept the grain continuous along parallel drawers - it should flow together nicely. The drawer fronts were carefully dimensioned to their final width and height at the miter saw and table saw, respectively, and then that fence setting on the table saw was used to trim the corresponding drawer sides to a matching dimension.

After labelling all parts, the half-dovetail rabbet drawer front joinery was cut at the router table. This is an easy drawer construction method that is similar to (but a bit sturdier than) the pinned rabbeted drawers likely present on that original Tansu.

Cutting a half-dovetail rabbet into a drawer front at the router table

After making grooves for the drawer bottoms and backs at the table saw, the corresponding parts to fit those grooves were fashioned from pine and poplar.

Scene during drawer construction

Finally, 35 mm dia. sockets were sunk into the drawer fronts using a Forstner bit at the drill press. I then drilled the mounting screw holes, 2 per socket.

Drilling out for the pulls

Next, a coat of shellac was applied to the pine box followed by some furniture wax. When glueing drawers, I like to unclamp the squared-up constructs and then slide them into their cubbies to finish curing. This way I can double-check that the drawer sits properly in its home. The shellacking will keep the pine resin at bay, and the wax assures that an errant glue drip will not unintentionally cement the drawers in. With all 25 parts completed, the drawers were individually glued and tucked away.

5 drawers

The joints at the drawer fronts were then pinned with 3/16 in. diameter pegs hammered from scrap elm.

Pounding out the pegs

After sawing things flush, and some final sanding, the interior drawer construction was complete. Still deciding on a finishing scheme for these, I put off the hardware installation for now.

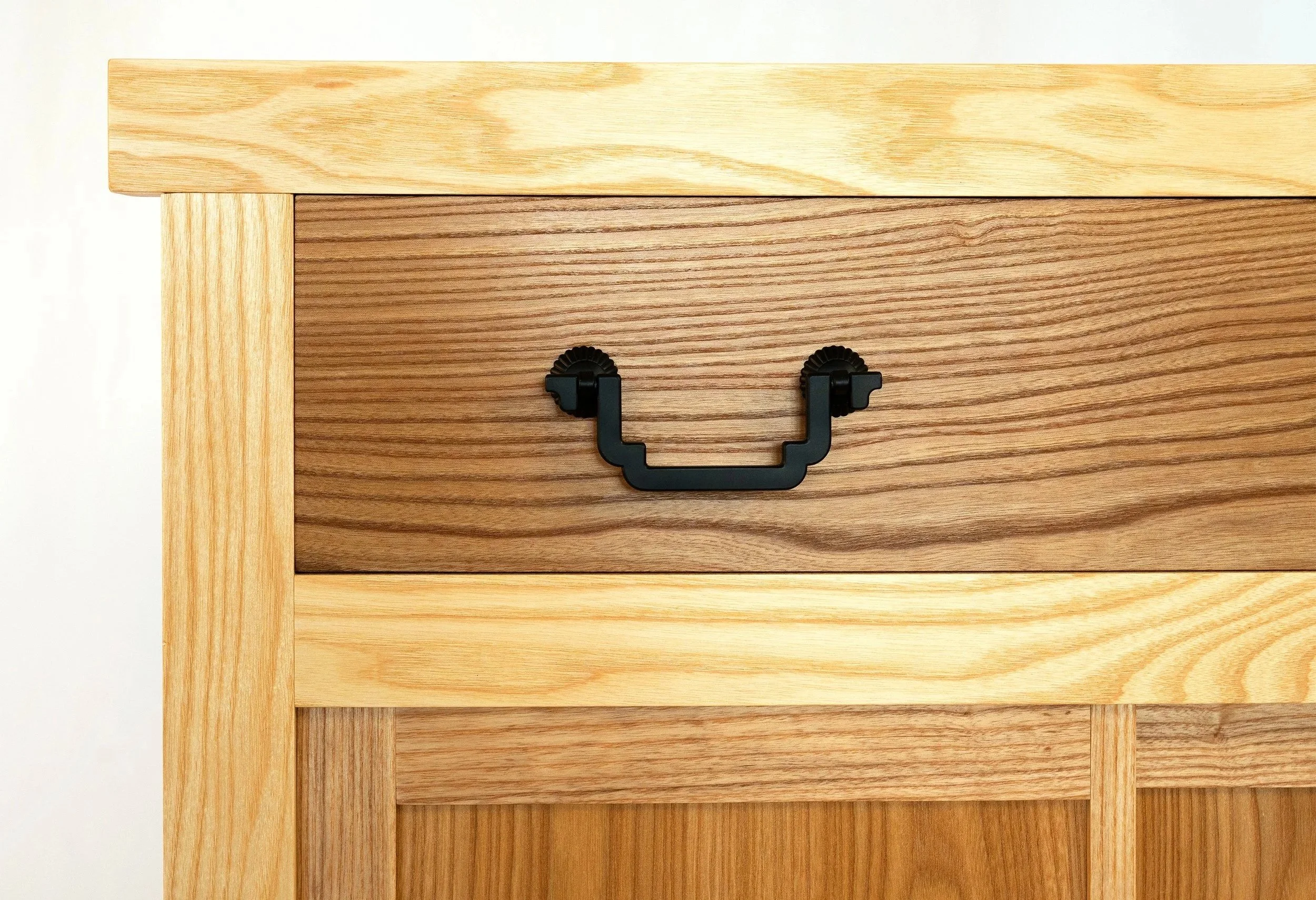

Drawers done

Sliding doors

Next came the sliding doors. These would be constructed from quarter sawn ash and elm to match the tansu sides.

Elm and ash door stock

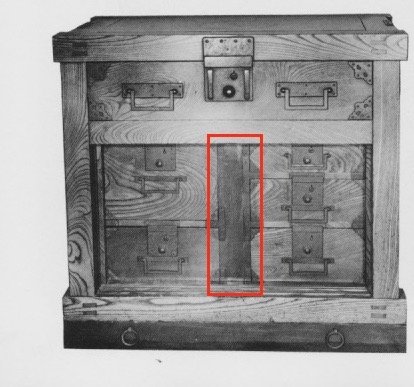

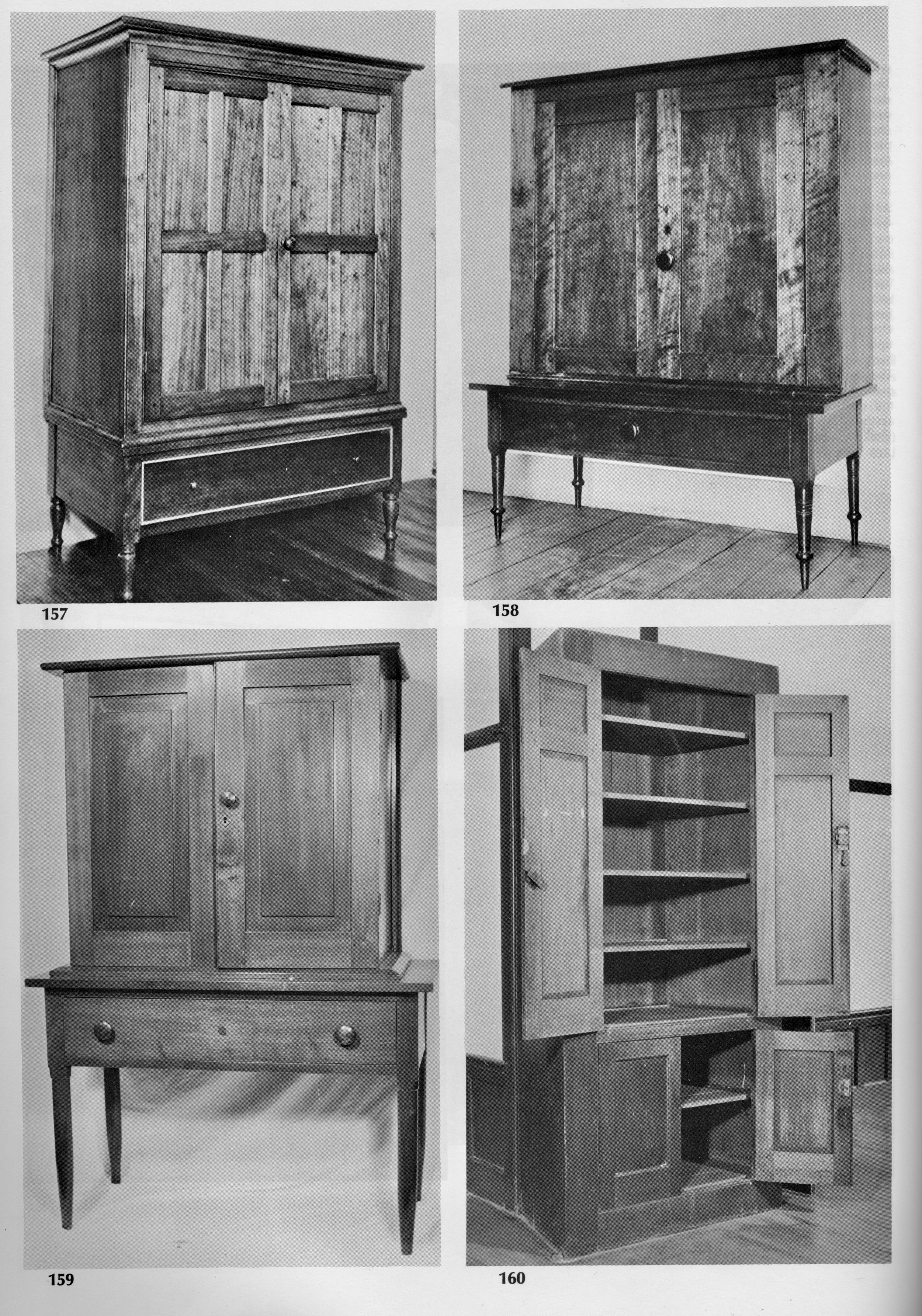

It was at this point that I realized the door design would need to be changed, for I had failed to account for sliding door overlap in the initial plan. You see, to achieve the intended look, I should have made the divider between the drawer and the shelf cavities wider - but that ship had sailed. It’s not really an issue with an open cavity, but with drawers hidden behind a symmetrically divided space, each door’s width needed to essentially conceal/reveal half of the entire opening. And since the center divider in the drawer box was 3/4 in. wide, that meant, to achieve the desired sliding door overlap, the interior stile of each door would need to be that dimension, at a maximum. The original plan called for double that width, but I think it will be okay. Lesson learned.

Picture of the exemplar tansu with doors removed. Note the extra wide central divider not included in my initial design.

from: Tansu: Traditional Japanese Cabinetry, by Ty and Kiyoko Heineken.

I used typical mortice and tenon joints for the door frames whose members were fashioned en masse at the table saw, jointer, thickness planer, miter saw and mortiser. A few hand tools were also employed - it’s fun to use all your stuff. The ash stiles and rails were grooved to accept 1/4 in. elm panels in between. These panels were prepared in the typical manner and, prior to assembly, they were chopped to size at the sliding miter saw, discarding a sacrificial 1 in. wide slice after each cut to keep the grain flowing naturally along the assembled door fronts.

Dry-fit, un-trimmed doors

Prior to glue-up, the 8 door panels were treated with a coat of gel polyurethane. I also trimmed 3/16 of an inch off of each panel’s width to accommodate 1/4 in. foam rubber “plugs” along one side that, by compression, would ensure the panels fit tightly within their slots and still allow for humidity expansion. The doors were then assembled with glue.

To fit the doors in their channels, I needed to rabbet the backsides of the tops and bottoms. This was done at the table saw. Now sliding within their tracks, I could mark the interior stiles and cut the doors to their final width dimension at the table saw.

Doors in place

Before leaving the doors I created the sockets that would house the pulls. These pulls, along with the big drawer handles were procured from Japan via the internet and a nice tansu hardware store called Morikuni. A 5/8 in. wide by 5/16 in. deep cut-out was needed here, and for this I used my small plunge router and a 5/8 in. diameter bit. To keep the socket parallel with the door edge I also made a simple jig out of scrap wood to guide the cut. The round ends of the groove were squared off using a chisel and it all went well.

Far: plunge router cut guided by a simple jig

Near: squaring-off the cut with a chisel

Pulls installed

Central Drawer

The final sub-assembly project was that large central drawer. This would be made from elm and poplar in a manner similar to those smaller drawers; just the front joints (double rabbet) and drawer bottom (birch plywood) would be changed. I selected a charming elm board for the drawer front and it all came together nicely.

Big drawer

Just a few details to take care of now. First, a shelf for the open cavity was prepared from 5/8 inch white pine, trimmed in elm. Next, six small ash boards were milled to serve as runners and kickers for the big drawer. These would be installed to the case interior during assembly, after which the final drawer fitting would take place. I also wanted to make stops for the interior drawers so that they would rest uniformly in their cubbies. These were fashioned from scrap pine and then glued into place. Lastly, the bottoms of those small drawers were lined with a blue felt.

Drawer parts (pulls, stops and felts) and shelf in place

Final Assembly & Finish

It was now time to take the dry-fit carcass apart and reassemble it with glue applied at the joints. For starters, the workbench was moved out of the way, the doors and drawers were set aside, and the remaining 42 parts arrayed in a manner to facilitate their orderly coupling.

Pre-assembled state

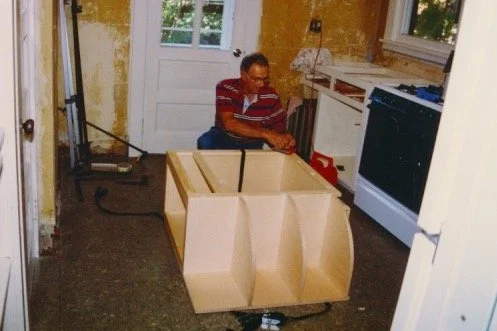

There are a lot of things to get “right” during assembly (while the glue clock ticks) and so I enlisted the help of my two sons. Together, we managed to agglutinate/hold/hammer/clamp the structure into being. Construction began with the top sub-assembly, followed by the bottom, back and sides. Next, the pine box was inserted and then enveloped as the front frame came together. Lastly, the top was lowered into place and the clamps applied. This was Super Bowl Sunday, and before my team even took the field it felt like we had already won! In fact, ours was a rare victory party on that sad day for New England.

Halfway there …

Box inserted

Spacer blocks used to register the slats

Glue-up lockdown

Following assembly, the runners and kickers were glued in place and the case was sanded to remove clamp marks/even the joint seams. Finally, the big drawer was planed and sanded to achieve a cozy fit. The doors and drawers were then removed for the final finishing.

You may have noticed that the elm panels and the small drawers and doors had been finished earlier in the work. Prior to that I had experimented on a few finishing schemes. The desired goal was to highlight the wood grain, give the object some wear protection and keep the sheen warm but not glossy. I ended up preferring the look of satin gel polyurethane followed by treatment with Howard’s Feed-N-Wax. I have used this duo on a few of my recent Projects and have been pleased with the ease of application and, more important, the final look & feel. It may not be the best for either elm or ash, but seemed to work well on the combo.

Only the carcass and big drawer were left to finish. Over the next few days, two coats of gel poly, a light caress with a gray Scotch-Brite pad followed by a good kneading with Howard’s brought out the beauty in these woods. And as an encore, the contacting door and drawer surfaces received a layer of furniture wax to keep things running smooth.

Finishing the wood

Whew! That was a long build, but a fun one all the way. Thanks for sticking it out.

Over the course of five months, a pre-planned series of sub-assemblies, along with some on-the-spot problem solving, has combined to produce a solid storage space and lovely piece of furniture. That’s the appeal of furniture making: applying one’s mind and hands in the manipulation of raw materials to create new and useful treasures. Now it’s your turn to have some fun, Mike. Enjoy!

Coin Chest complete

Peaceful Patch

I like the word “patch”. It’s a nostalgic noun that evokes the scene of a neatly arranged vegetable garden (think: Beatrix Potter). It comes from the old French word “piece” which, apparently via the dialect variant “pieche”, had further evolved into a distinct English species able to coexist with the original (think: horses and zebras). According to the O.E.D., Brits like Beatrix will use the word “patch” to mean an area for which someone is responsible or in which they operate. I am happy to call the Red Top Workshop my patch.

Using the British definition, it’s likely that all of us can identify a “patch” that we tend, and this might be a useful way to reflect on our condition: What is your purpose while in the patch? How do you feel in the patch? What do you gain from your patch? Think about it.

In my patch I find tranquility. To be sure, challenges, frustrations and victories occur every day in my patch. These are all good experiences that, together, make up the creative process essential for our humanity (see also: win back art). I am at peace in my patch - working things out of wood and absorbing satisfaction from the act. Merely pausing to think about things in this way is fulfilling.

But patches are not just a dreamy sanctuary - things get accomplished in a patch. Food, furniture and [insert passion here] are produced in patches. In addition to a couple refurbishing Projects, in 2025 I produced new versions of the traditional hutch and storage cabinet; reproduced a classic Korean stand; and designed a set of cornices in the neo-bungalow style. The new term “neo-bungalow” was even coined in my patch. Not a bad year!

Just as the word “patch” has a traceable origin, surely one’s own patch does not spring from a vacuum. It comes from a prior concept, held by the tender, of that area for which they choose to take responsibility. I owe my father, Ed, a good deal of credit for the concept behind my Red Top Workshop patch. Upon retirement, Dad spent many hours in his basement woodworking shop, fulfilled in the act of making gifts and satisfying furniture requests from family. He accomplished a lot down there, and I own many big & small pieces produced from that patch.

Edward Goulet putting the finishing touches on a homemade cabinet he contributed to our kitchen renovation in 1995.

These works are more precious to me, today, having lost my father at age 96 a couple weeks ago. I now appreciate that he gave me much more than towel holders, benches and boxes. He helped to build my patch. Thanks Dad.

Peace.

Me and Dad in my patch (2016)

Built for Service

Last year I was gifted an item that once belonged to my grandfather, Otto, rescued by my brother-in-law, Brooks, during an earlier house clean out. It’s an old furniture piece that I had no idea existed until I was made the caretaker. Unexpected acquisitions like this are truly gifts to be savored. They bring instant joy along with a new responsibility, gladly accepted, for custody of an heirloom. I am talking about a machinist’s chest from the “Built for Service” tool chest series manufactured by the Pilliod Lumber Company of Swanton, Ohio.

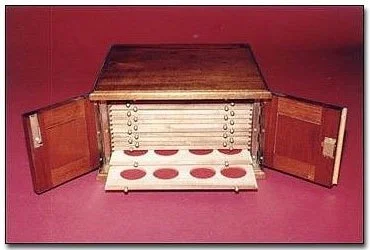

Machinist chest of old

I don’t recall ever seeing this early twentieth century chest around my grandfather’s workshop and so I have nothing to add regarding provenance. What’s certain is that the chest (cabinet?) contains six small drawers behind a locking front panel. The contents: some metal lathe cutters, drill bits and hand taps, suggest that it once supported the work of a machinist - a precision metalworker. It contained some nice old measuring tools as well, but the value to me was in the container. Fashioned from quarter sawn white oak, stained dark, with a leather handle and stately brass hardware, this 17 x 10 x 8 in. chest had it all.

Six drawers nestled behind lock and key (note label on bottom drawer)

Loaded with tools and bits.

This was a refurbishing (i.e., not a refinishing) Project. By cleaning it up and replacing the missing parts, my primary goal was to make the chest useful again. I had no desire to botox the evidence of wear earned over a lifetime of service. A second goal was to create a tool box for my clockmaking paraphernalia.

History

Most of what I know about this piece comes from an informative blog post (they’re out there!) by a Canadian designer named “Mister G”. His blog, Progress is fine, but it’s gone on for too long, is an entertaining historical commentary on items that he refers to as “old forgotten mechanical crap, things with wheels and/or wings”. If you like any of that stuff you’ll find it worth a look.

According to Mr. G, The Pilliod Lumber Company was founded by T. J. Pilliod in 1896, and they manufactured a variety of small chests for the home and workplace. As with any enterprise, a history of The Pilliod Lumber Co., found in the blog post, records the adaptations necessary for survival amidst the ever shifting selection pressures associated with new technology and market demand (read: acquisitions and restructurings). The final remnant of Pilliod’s business succumbed earlier this century and that final fact makes this refurbishing effort even more meaningful, to me.

Popular Mechanics advertisement, March 1924

from: Mister G. (2013, March 6). “Vanished Makes: Pilliod Cabinet Company, Swanson, Ohio” [Blog post]. Progress is fine, but it’s gone on for too long.

Refurbishment

All refurbishing begins with a dust cloth and vacuum cleaner, though these are seldom listed in the credits. That initial sweep was followed by a wash with Murphy’s Oil Soap in warm water, a rub down with mineral spirits to remove decades of oily grime, and then a second Murphy’s treatment which sufficiently cleaned the surfaces. There is a line between unwanted dirt and valued patina, and care was taken not to cross into the patina zone.

In addition to dirt there were those usual white spots. Anyone who has refinished furniture knows what I’m referring to. It’s hard to fathom, but the conversation must have gone something like this:

“Honey?! I think I’ll paint the ceiling today.”

“That’s nice, Dear. Don’t forget to spread out all our furniture to catch the drips. Need help with the piano?”

Am I right??? (I added the piano part.) Anyway, those dots of lead were not easily scratched-off the chest and so I decided they could stay. Sheesh!

Collateral damage

Unfortunately, the filthy felt drawer liners were beyond hope and needed to be replaced. Their removal was accomplished by the two step process of: skinning what could be pulled away by hand; followed by a shave using that one shop chisel applied to everything except woodworking. I resorted to mechanical methods because the crystalized glue securing the felt appeared to be the same hide glue used for drawer construction and I did not want to loosen any parts by soaking those drawers in water. Curiously, one drawer had already been re-lined with contact paper. Wouldn’t you love to know the story there? “These five, oil-soaked and smelly felts can stay, but THAT one has to go!”

Shaving Pilliod’s pelts

The drawers were re-lined using today’s 100% polyester felt, and I took it easy on the glue. Next, all wood surfaces were perked-up with an application of Howard’s Feed-N-Wax. I was able to rejuvenate the dry leather handle a bit, too, using prosoft® baseball glove conditioner. Things were beginning to brighten.

Green New Deal

The final step involved the drawer knobs. As evident from that earlier picture, 3 of the original 9 knobs had pulled loose and were missing, one being replaced by a Phillip’s screw implant. In vain, I searched the Web for duplicates. What I found were some small brass knobs from Timesavers, an online clock parts store, that would serve as suitable substitutes. The remaining originals were cleaned-up with mineral spirits, waxed and re-mounted.

All parts in place

Drawers re-loaded

Back in Service

Thanks for reading. And thank you Mister G. for the service you do to humanity by keeping history alive and accessible.

The Big One

According to my father Ed, his father, Sam, when coming to the end of a big job would often say: “Here’s the one we were looking for.” It was a simple observation, no doubt meant to elicit joy in his farmhands: Ed and three older sisters. I like to utter that one, too, when completing certain jobs. To be clear, my “jobs” are nothing compared to farming chores of the early twentieth century; when fields were plowed with horses and hay was pitched with forks. Still, it is satisfying to declare that you have, at last, finished the final task. The job under discussion here is the fourth and final cornice for our living room: the Big One.

Once upon a time on the farm

Design

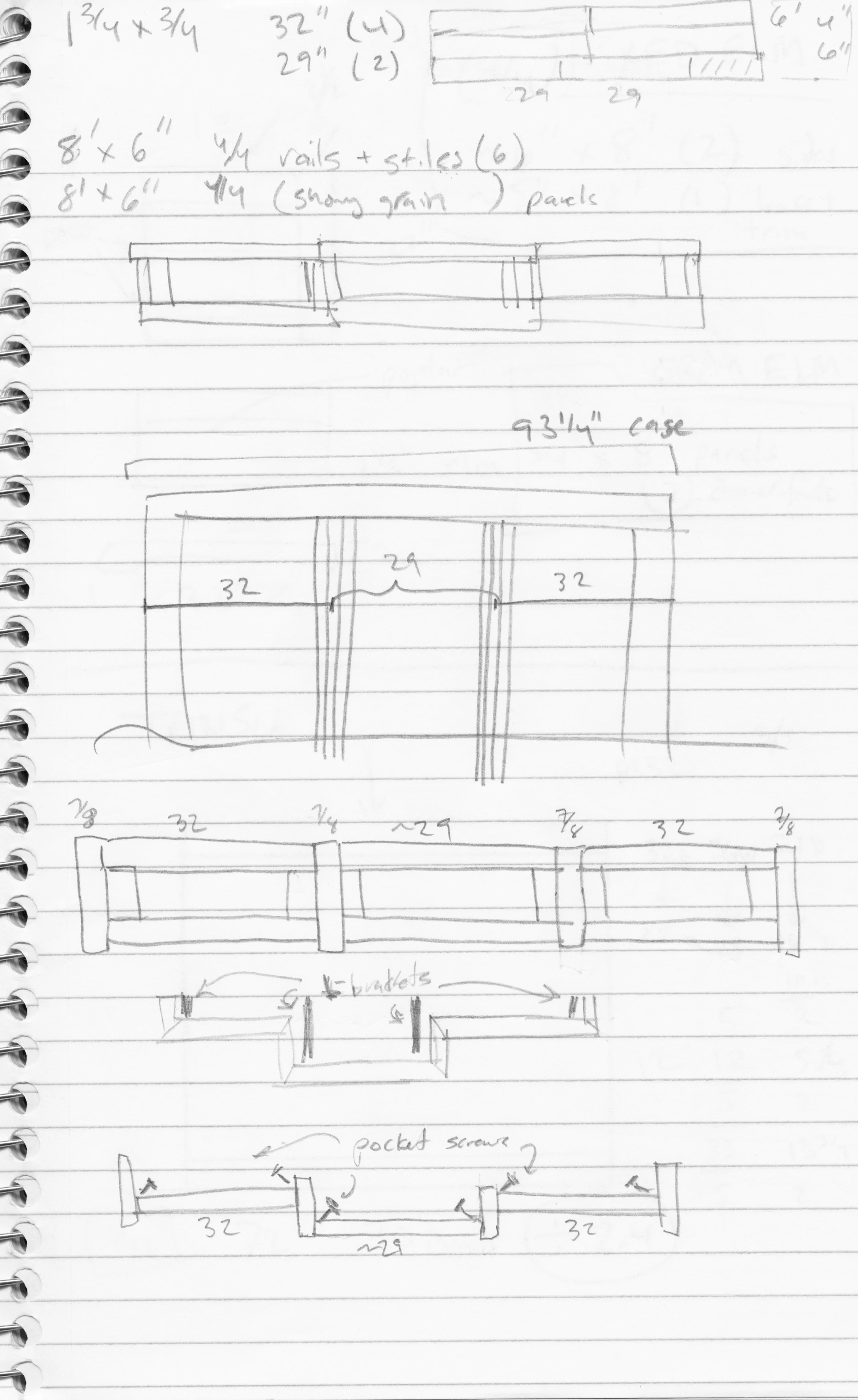

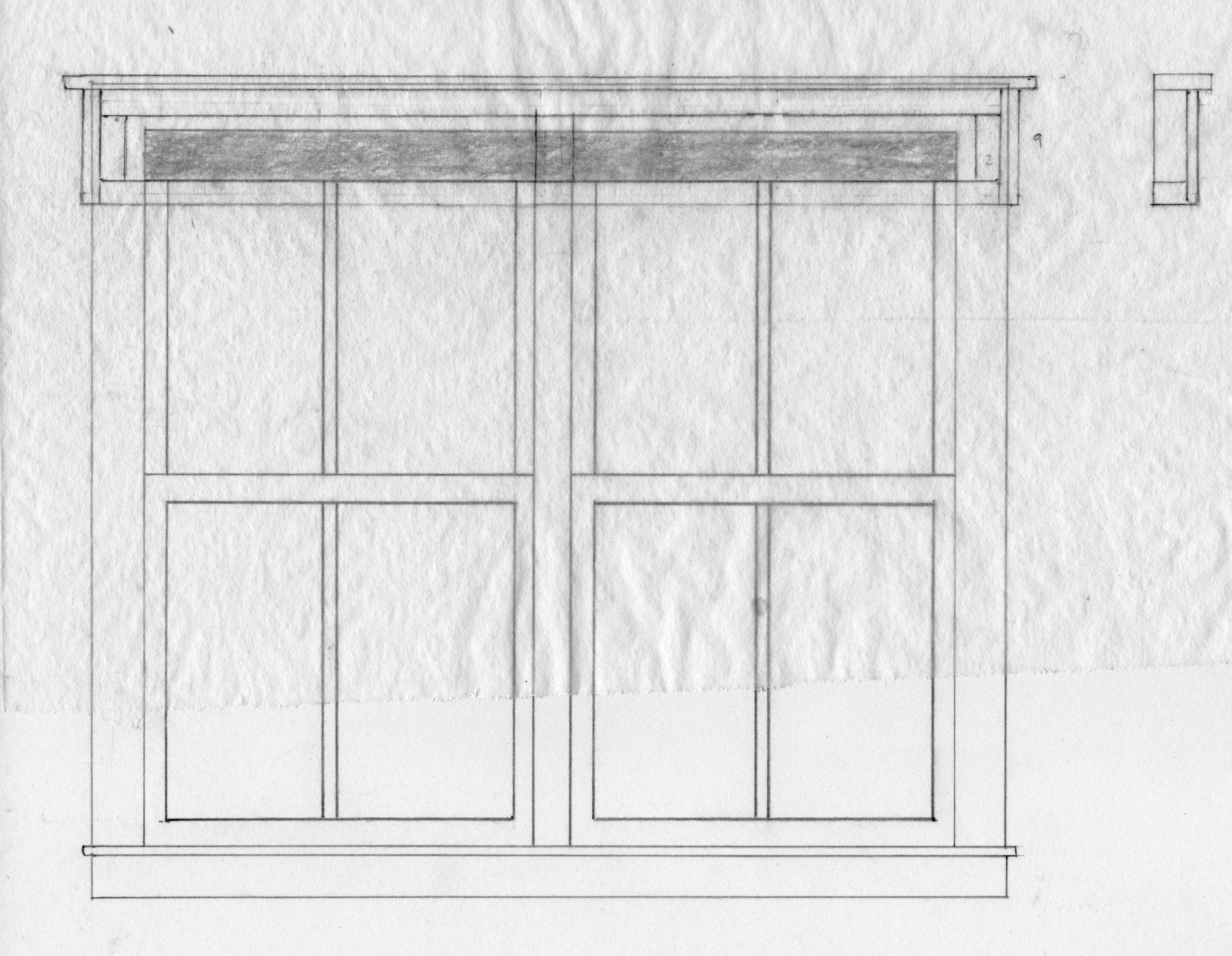

The design for this cornice is very similar to the last one, with just the panel dimensions changed to accommodate the new window sizes. I hope it works. That so-called “sophomore cornice” was mounted atop three windows of identical widths, whereas this one includes a large, 5 foot central window flanked by two smaller versions in what was once a dining room that overlooks the backyard.

“Dining room” windows

It should be a straightforward build, but before getting started a simple plan was produced to put the dimensions on paper and glimpse the ensemble’s relative proportions.

Rough plan

Materials

Four 4/4 white oak boards, three quarter sawn and one rift sawn, were procured from Reader’s and marked with chalk for processing into stiles, rails, panels and trim.

White oak cornice wood

Dimensioning, Assembly & Finish

Using a few oak pattern pieces saved from the prior build, to help set the tool fences, there is nothing remarkable about this construction story and so I’ll spare the details and just leave you to imagine the fun. <pause>

Once the cutting and dressing operations were finished, the panels were constructed as 3 sub-assemblies.

Cornice panels

To complete the build, the end caps were attached to the smaller panels with pocket screws, and then these sections were connected to the center panel in a similar manner. At almost 9 feet in length it was a challenge to support and hold the thing square while it was coming together. I’m not saying I need a bigger workshop, just maybe more clamps.

Connecting the panels together

Following assembly, the top trim was fabricated from rift sawn wood and attached as before. The cornice was then treated with two applications of boiled linseed oil and allowed to cure for a few days afterwards.

Finished cornice (upside down)

Lastly, my furniture hand (son), Ben, stopped by to assist with installation and to find “the one we were looking for”.

The Big One in its place

Coin Chest ep. 1

In for a penny, in for a pound

Growing up, my brother Mike and I collected coins - in addition to stamps, fossils, baseball cards and other treasures common to a 1960s-70s youth. Curating our small collections taught us a lot of things not covered in school, and spawned many happy memories in the process. Those passions were precipitously “parked” to make room for college and subsequent responsibilities but, following 45 years of adulthood, Mike is back into his coins and now has the resources to move them out of their cigar box abode. He has requested a suitable cabinet to store his collection and I am most happy to oblige.

Design

Where to begin? Well, it turns out there is a canonical “coin cabinet” that has been around for ages. It is a fine wooden case, typically made from mahogany, with layers of thin drawers that feature circular cut-outs to nestle each individual member of your collection. Beautiful, but that’s not what he was after.

Mahogany coin cabinet from the fine craftsmen at coincabinets.com

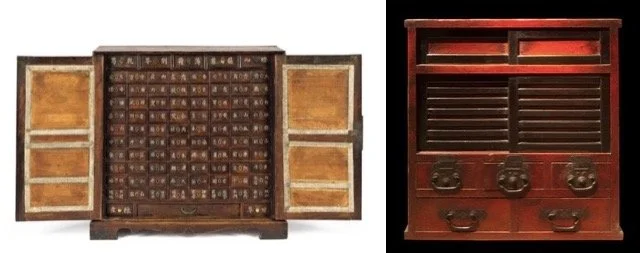

You see, Mike intends to enjoy his collection, not entomb it. He needs a place to keep things organized, and one that can handle a variety of coin holders, rolls, books and small boxes. A cabinet for this purpose needs to provide small storage spaces with easy access and room to grow. Considering this mission not a lot of Western furniture items come to mind, however, there are some East Asian pieces that could readily do the job. The multi-drawered Asian apothecary cabinets could work, but their monotonous configuration might not suit the access requirement so well. (Where did I put those buffalo nickels, again?) Various Japanese merchant chests, a version of which I have made previously, might also serve the new purpose of housing a coin collection.

Apothecary cabinet (Korean) and Merchant chest (Japanese), examples of small, multi-compartment furnishings found online

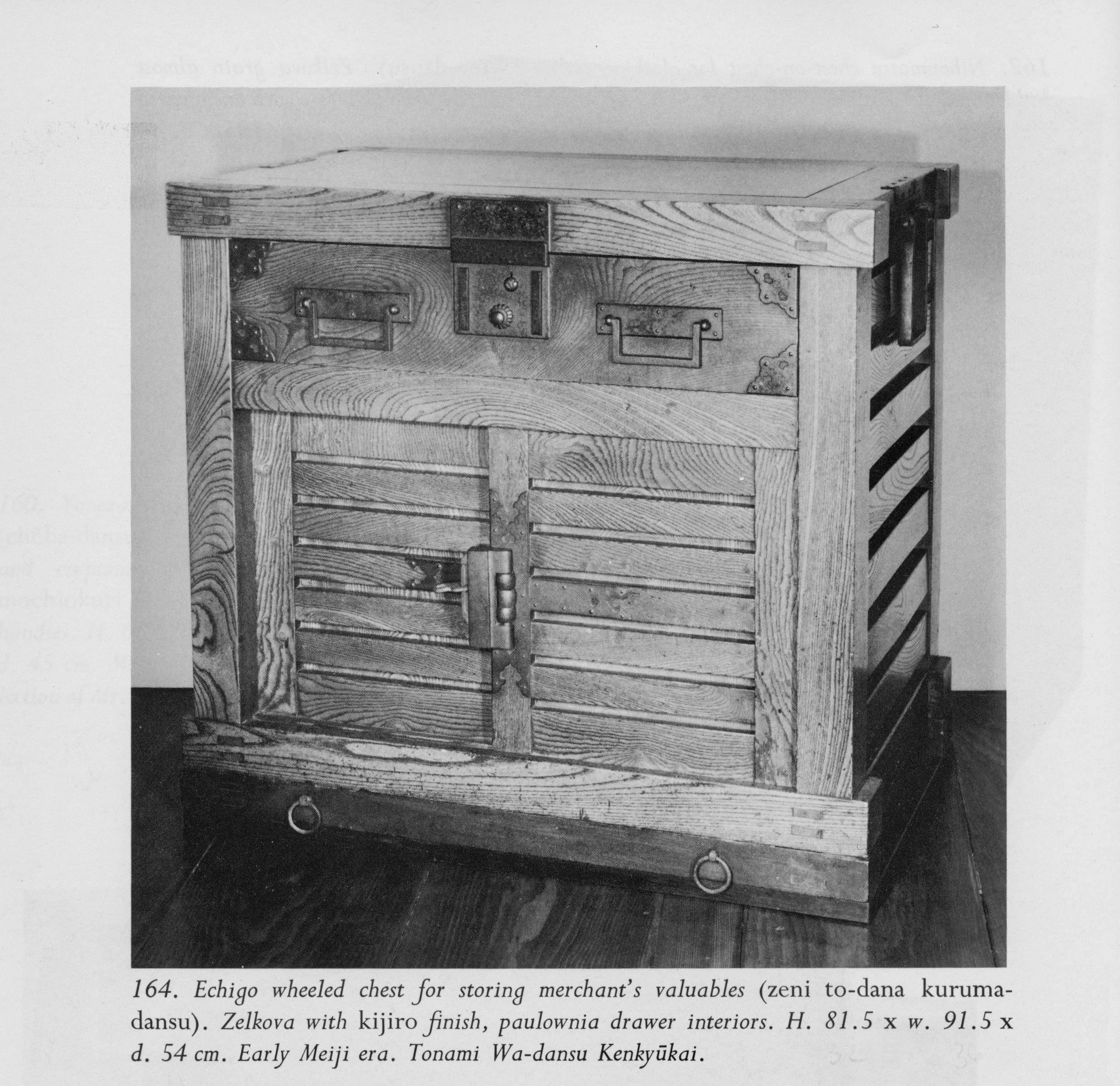

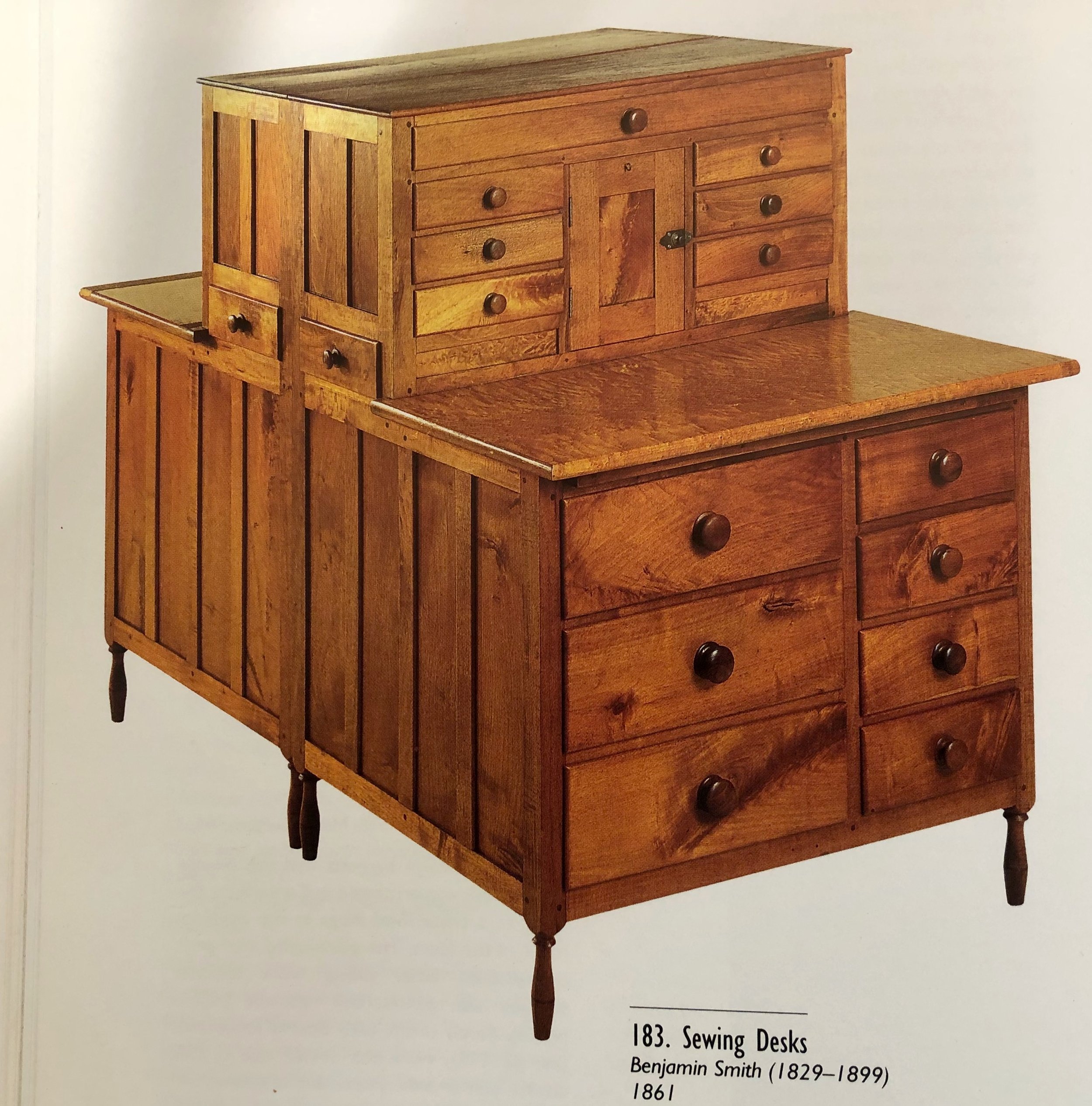

The Japanese chests (tansu) seemed most appropriate, and there are many to choose from. Over time, the versatile tansu form has been adapted for the storage of almost everything, with some providing safe-like security. And every tansu type has distinct sub-species that differ by their geographic region of production, which means there is a lot of design inspiration out there. After some back and forth, we decided that a specific merchant’s chest, a zeni to-dana (translation: money chest with sliding doors), from the Echigo province would be a great choice. This particular specimen from the early Meiji era (1868-1912) was also a wheeled chest (karuma dansu), useful for exiting a burning dwelling with your most valuable possessions in tow, but we plan to omit the wheeled base on ours.

Zeni to-dana exemplar from: Tansu: Traditional Japanese Cabinetry, by Ty and Kiyoko Heineken.

Behind the locked sliding doors of this chest there are a set of drawers that could be further locked for security. We liked this “compartment within a compartment” feature, but would dispense with the locks. The plan for ours would be for one side of the cavity to contain drawers while the other would have open, adjustable shelving. The large, upper drawer might also be compartmentalized. In this first episode we will complete the carcass, saving the doors and drawers for later.

Coin chest, rough plan

Materials

That original zeni to-dana was made from zelkova, a member of the elm family native to East Asia. Zelkova was a popular furniture wood in Japan and I find the grain character of this species to be most fetching. It is not readily available as lumber in the West, however, but there is elm and ash and those were my quarry as I entered Reader’s Harwood Supply, my new go to yard for quality boards. Elm comes in two varieties at Reader’s: red and gray. On the day of my visit they had much more of the red in stock and so I picked through their 4/4 boards and got a few of the best ones. I needed bulkier material for much of the carcass and so an 8/4 (2 inch thick) ash board was selected as well as some 4/4 quarter sawn ash for the slats. The plan was to construct the framework from ash and the mirror boards and drawer fronts from elm. Should look nice!

Lumber (L to R): quater sawn ash, plain sawn ash, red elm

Dimensioning

The bulky frame for this chest is constructed of 2 x 2 in. ash material, and to create these that large 8/4 plank was cross cut into rough lengths, ripped at the band saw and then made square at the jointer and thickness planer. This produced a stock of 14 poles for further modification.

Frame stock

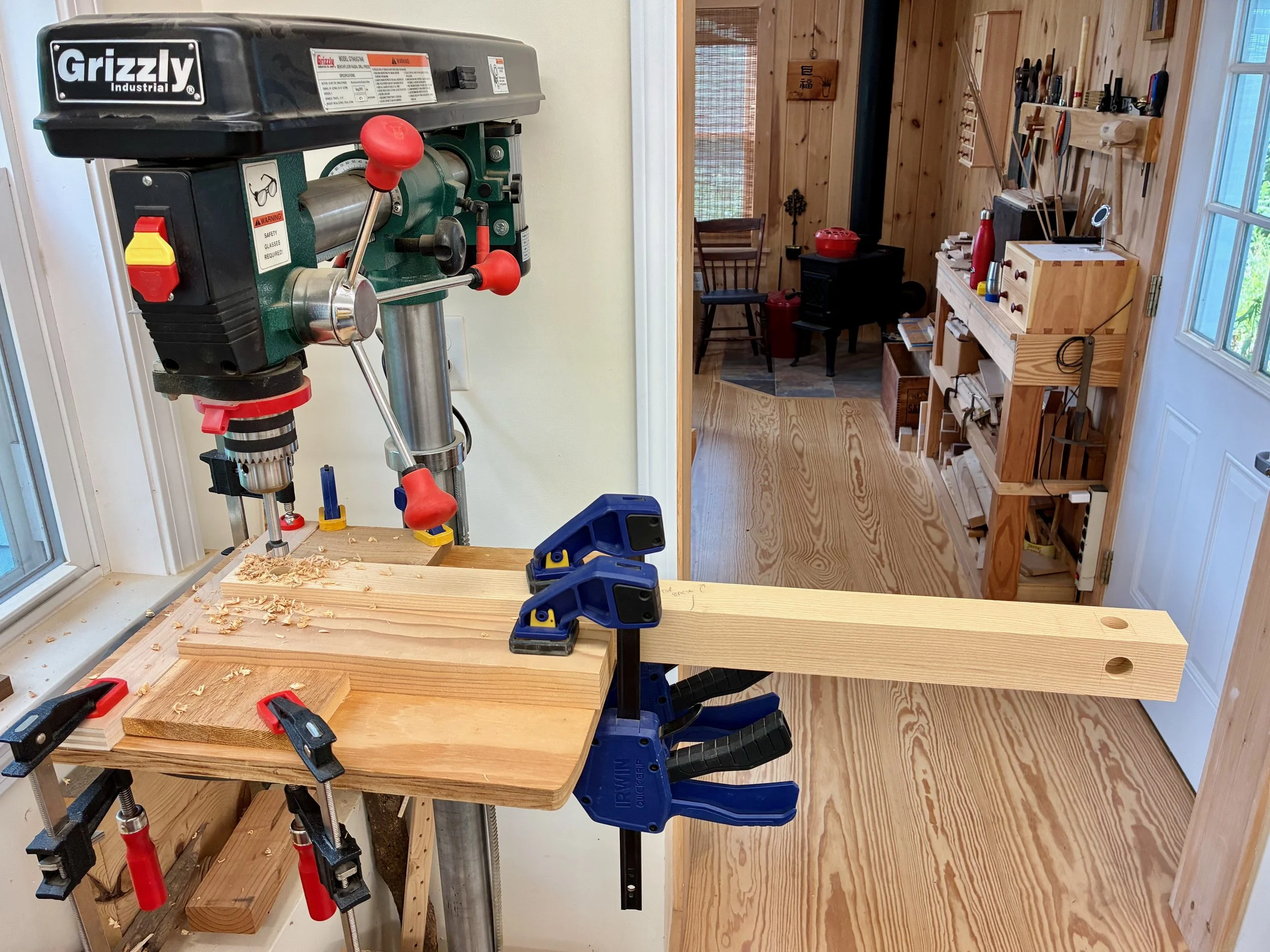

From here it was a matter of cutting everything to final length and then fashioning the tenons, mortises and grooves of the joinery. Everything starts with the top and bottom rails and the mortises within these that would hold the side posts and cross rails. Ash is a tough wood to mortise and I needed to bore sixteen 1 in. square holes that were 3/4 in. deep. To make the experience pleasurable, I hollowed out the centers of these sockets with a Forstner bit at the drill press before squaring them off at the mortiser - much easier this way! A simple slot jig was constructed by clamping a few boards onto the drill press table to allow for quick and uniform production.

Drilling out the mortise centers

Following a bit of chisel clean-up the mortises were complete. These were then used to define the tenons to be fashioned at the ends of the rails and posts. After cutting the members to final length the tenons were formed in a two step process. First, the shoulders were defined at the sliding miter saw, where a shallow cut was made on all four sides of the post to create a joining edge. Next, the cheeks were cut at the table saw using a tenoning jig - four passes per tenon. Creating tenons by this manner is a bit more involved than using a dado stack and cross cut sled, but the result is a clean joint element that is easy to fit.

Making the first of four cuts with a tenoning jig to create the cheeks (note the finished tenon at top of rail)

After a bit of chisel work, the parts were made to fit snugly at each joint, but in order to dry-fit the entire frame I needed to shave a corner off of most tenons to accommodate their perpendicular mating within adjacent mortises. This was done by marking and then slicing-off these corners with my dovetail saw.

Paring a corner off of the tenons

With the tenons pared, the frame came together during a maiden dry-fit. From here, the positions of all subsequent grooves and mortises could be marked in pencil to ensure their accurate formation. It is easy to get the ends and faces of 14 frame parts confused when disassembled into a pile of poles, so this marking step is key!

Dry-fit frame

Every frame member would receive at least one groove to house a sliding door or panel. Each side post also required a series of seven mortises to secure the tenoned slats. Lots of secondary joint work to do here. Variously employing the table saw, mortiser and router table, each series of cuts were set up and then executed as a batch to maintain uniformity. Two side panels called “mirror boards” were also prepared from red elm, whereas plywood was used for the out-of-sight back and bottom. Steadily, over a weeks’ time, the carcass came together component-by-component.

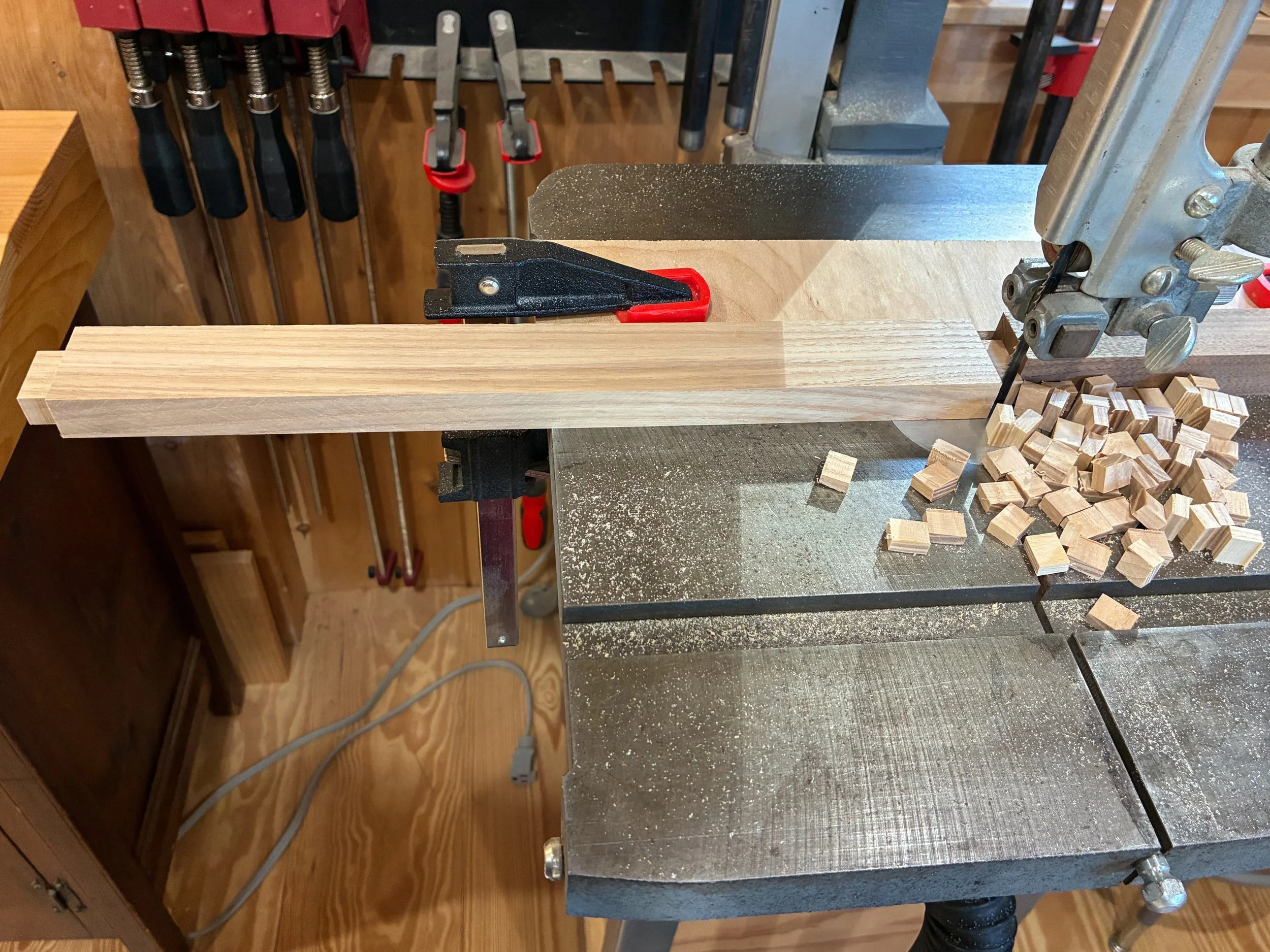

Clipping the edges off of 28 slat tenons at the band saw

Gluing-up the elm mirror boards

Test fitting the sides

Back and bottom fashioned from plywood

The top came last. Construction-wise it is identical to the bottom, but instead of 3/4 in. plywood for the panel I used red elm. One of the elm boards selected at the lumberyard possessed a wild and flowing grain pattern which I thought would make for a lively top. That untamed grain was also responsible for the undulating surface, which twisted and warped its way along the entire 7 foot length.

Red elm “diamond” in the rough

After lopping-off 14 inches of “whip tail” from both ends, the remaining board was cut in two. Even after surgery, both sections were twisted by up to 3/8 of an inch along their 28 in. length and this would need to be remedied before processing further. I decided to use the thickness planer for the job, but first needed to create a new jig to assist the operation. The trick is to first make one side of each board perfectly flat. That flat side can then be placed on the thickness planer’s bed (sans jig) and the uneven, opposite side made parallel by repeated passes through the planer. A “sled” jig to enable the operation was made from a sheet of mdf and a scrap piece of oak. In the event, an elm board was laid onto the sled surface and shimmed underneath to create a stable situation with no rocking action. The sled-mounted elm was then repeatedly passed through the planer, making light cuts, until the entire upper surface was flat and smooth.

Twisted elm board mounted on the planer sled

Elm and sled exiting the planer on its way to becoming flat

With a bit of care and patience, the elm/sled/planer combo produced two flat boards ready for mating together. Biscuit slots were cut into jointed edges and the boards were glued-up to make a full-sized panel. After trimming to final dimensions, filling some crack defects with epoxy, and then smoothing the surfaces, the underside was rabbeted at the table saw to fit within a groove in the top frame.

Elm panel dry-fit into the frame

Finally, I routed some grooves into the front framework to serve as sliding door channels and then the entire carcass was assembled in a dry-fit - 34 parts, in all. The next steps are to create: 1. the sliding doors and drawer for the chest; 2. a case for the interior drawers; and then 3. the interior drawers themselves. I believe I’ll need to squeeze that drawer case into the carcass frame prior to a final glue-up and so I am leaving the Project at this stage for now. Please stay tuned for the completion story in episode 2.

Coin chest carcass

Sophomore Cornice

Here’s a timeless question fraught with feelings:

I liked the last one, but how will the next one compare?

This natural query can elicit thrills or, when the stakes are high, dread. For me, it brings back memories of hope; as in tearing the plastic from a band’s new album and hoping you will like it as much as you enjoyed their last. Sometimes you do - sometimes you don’t. More than a feeling, that was my state while embarking on this Project.

Notable first and second efforts

I took a break after completing the Craftsman Cornices for the purpose of working with a different wood and joinery scheme. But, to complete my neo-bungalow living room there were two more window banks to outfit so I’d best keep at it. The window areas were different enough that it seemed prudent to tackle them one at a time. The current Project addresses a trio of identical windows on the West wall that, today, are a feature of our living room but were once part of a bedroom (it’s complicated).

Target windows

Design

Much like those Boston album covers the new design would be a variation on the old; no new features, just a new take. The big idea was to add some dimensionality to the sequence of three framed panels by protruding one or two beyond the other(s); just enough to add interest without overpowering the scene. All of the part dimensions would match the “old” cornices, as would the materials, so the only remaining choice was: one lump, or two?

Hastily jotted construction plan and mill bill

I know of no existing design precedent, and think both patterns would look fine. The deciding factor for the use of two lumps was the peculiar fact that the wheel for this window’s blind cord was temperamental, and prone to coming unhitched when operated inattentively. It was hoped that a protruding panel on the end would provide enough extra space to rig something (TBD) that would allow for re-threading the spool, as needed, without dismounting the heavy cornice.

Materials

White oak boards, two quarter sawn and one rift sawn, were procured from Reader’s Hardwood Supply. I purchased these among a bunch of boards for use in the next project and so forgot to take a picture before diving in.

Dimensioning

With forethought, I had saved a few cut-offs from the original Craftsman Cornice. By definition these are milled to the exact dimensions (thicknesses, dado widths/depths, etc) required here and so were used to set the fences and blade heights for the new build. This made everything super easy and within a couple days I had all of the major parts prepared for the three panels.

Dry-fit panel sections

The cornice would be constructed from the inside out. This meant getting the dimensions of the central section properly established so that the two connecting boards could then be added, followed by the flanking sections, trimmed to their correct final length. I decided on a 1 inch offset for the center section and, using rift sawn stock, constructed two connecting boards with shallow dadoes to impart this pattern. A rift sawn board was also used to create the top trim in three sections, as well as the two end panels.

Playing with a connecting board (center) and trim joint

Assembly and Finish

Prior to assembly, the panels were treated with their first course of boiled linseed oil. Following this the central section of the cornice was glued together and clamped. The connecting boards were then attached to each end of the section with glue and pocket screws. With this section now resting on the actual window sill I could take final measurements to determine the exact lengths of the remaining sections. Back in the workshop, the outer section rails and panels were trimmed to final length and then assembled.

Glueing the outer sections, central section in background

To mount the end panels I drilled holes for pocket screws on the left side, but I left the right (window blind cord) side alone. Next, the sections were put together with pocket screws, forming an 8 foot long cornice body. The trim parts were then mitered on a 45° angle, modified with chisels on the underside to accommodate profiles of connecting and end pieces, and then trimmed to their final length.

Sizing the top trim on the fully assembled body

To cover the end grain where the trim boards jog around the central section I glued a small piece of homemade veneer before sizing and mounting the center trim span.

Veneer covering end grain of trim

To solve for the removable end panel, the right side panel was attached using magnets along the edge; the trim’s top resting on an auxiliary board behind. These can be modified further if they are not able to keep things tight, but I think they will work.

End panel with magnet next to a reclining cornice section with matching magnet and auxiliary board (after finish)

At last it was time to complete the oil finish by applying two coats of boiled linseed oil, 24 hours apart. This livened the grain while adding some color to the cornice.

Finished cornice

Installation was just a matter of settling the piece onto 4 pre-installed angle brackets along the top of the window trim and cinching things tight with a couple of zip ties. It also looks like the removable end panel will work as intended. Terrific!

Feelin’ Satisfied

Three Story Table

Actually, it’s not a “table”, it’s a sabang-t’akja. But, unless you speak Korean, that name can be a mouthful and maybe that’s why it has been translated into so many aliases over the years. Anyway, this Project is my own translation of the classic sabang-t’akja. Please come along.

I’ll admit that it’s hard to nail down the exact English definition of the Korean “sabang-t’akja”. The t’akja part is easy, generally translated as “open-shelved stand”. But when preceded by sabang, a word that in Korean can variously mean: 1. four sides; 2. in all directions; or 3. everywhere, this two-word noun literally translates to “ a shelf that is opened in four ways”. And I have seen that exact “name” for this item online, however, my furniture books tend to rely on real world function when they refer to it as a “book storage and display stand”. We’ll go with that one for now as use defines meaning. Astute readers may also recall that “storage and display” was the purpose of a hallway hutch, recently completed under the Red Top. One can contemplate the structures of these Eastern and Western furniture items and marvel at the products of convergent evolution underway in opposite hemispheres of the earth.

Examples of a Korean sabang-t’akja and American country style hutch found online

In the late Joseon Period (1392-1897), when sabang-t’akja were popular, they were furnishings found in the Master’s room (sarangbang) of a Korean home (hanok), what today we might call a study, where book storage and the display of “manly” objects was its function. I visited the Namsangol Hanok Village museum in Seoul during a visit in 2016 and saw many sabang-t’akja among the furnishings in their collection. This picture of a sarangbang scene was snapped there.

Book storage and display stand (sabang-t’akja) in the sarangbang

The sabang-t’akja Project described here is different - it’s for my wife, Joung. You see, she is becoming quite the knitter and has accumulated many skeins and needles in the process. She deserves a proper place to store these and to display some of her favorite things. I aim to please.

Design

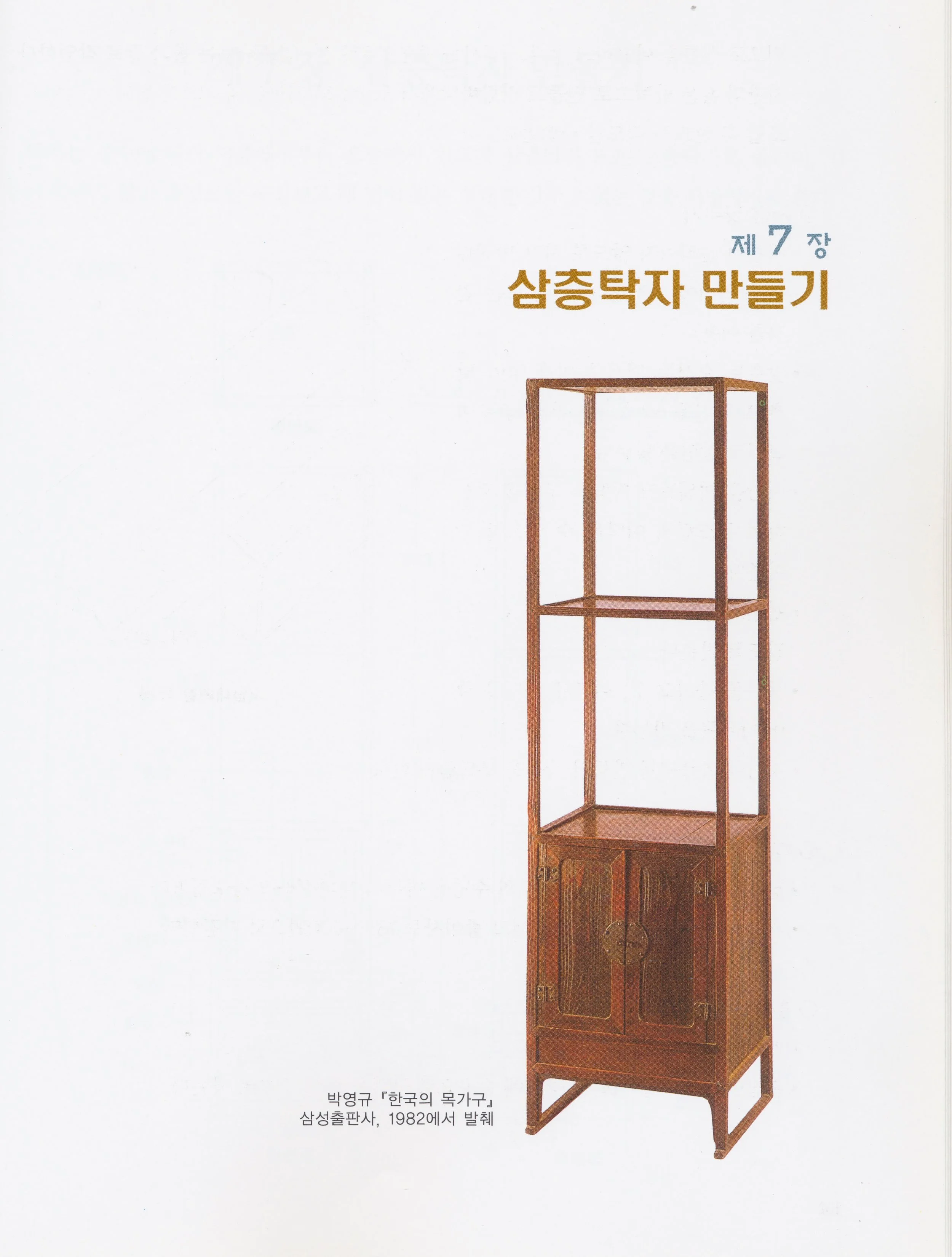

It was easy to choose the version of a “storage and display stand” for this build as I have had my eye on it ever since the 2016 Korea trip. During that visit I picked-up a nice little book called Making Traditional Wooden Furniture and was smitten with the dainty version described in the back section where some construction plans could be found. Oh, and according to Google Translate, they give it a new name: “Three Story Table”.

“Chapter 7

Making a Three Story Table”

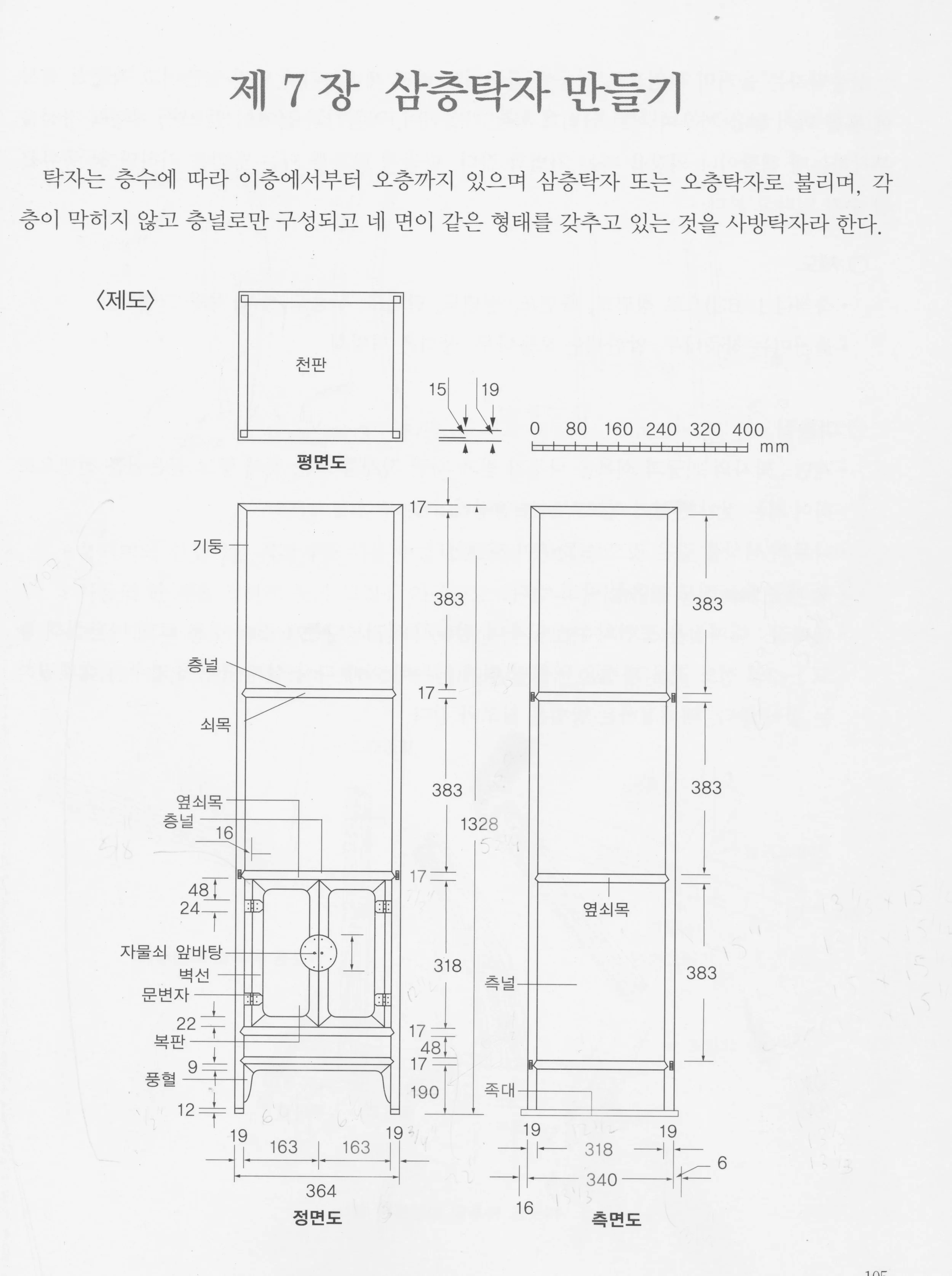

The construction plan was carefully rendered on page 105 and dimensioned in millimeters, a language almost as foreign to me as the accompanying Hangul write-up. No worries, I have apps on my phone that can translate both!

Three Story Table plans (original)

I converted the mm spans into inches and then encountered a problem: at a finished height of just over 4 feet, the piece described would be too short. A “three story table” of that height might be perfect for a floor-sitting Korean lifestyle, but it would not blend well with the other furnishings in our living room. No worries, I figured I could apply a 1.3x scaling factor to every number and enlarge the item proportionally. That works fine in “decimal land” but it gets cumbersome when translating things back to inches, the language of my workshop tools. (One millimeter = 197/5,000th of an inch). I was about to begin the tedious conversions, rounding numbers up or down to the nearest 1/16th of an inch, when I recalled I had essentially made this furniture piece two years ago: the Korean Stand. For that Project I had divined the measurements from a small photograph and used those plans to produce a beautifully proportioned set of open shelves. I could essentially use the same part dimensions for this one, tweak a few details to add the cabinet section and make a respectable version of the sabang-t’akja depicted in the plans above. Reduce, reuse, recycle (and stay sane)!

Starting from the Korean Stand work, a rough plan was sketched at 3/32 scale (in inches) of a 3 shelf unit with a doored cabinet enclosing the bottom section and standing 5 feet tall. It looked nice. My only change would be to convert the panel below the doors into a handy drawer for storage.

New and Improved “Three Story Table”

Materials

I wanted a special wood for this piece that in nineteenth century Korea would almost certainly have been fashioned from paulownia. Paulownia, second only to balsa as the softest hardwood, was favored in the East for its lightness and supposed insect resistance, however, it is difficult to source in the Eastern United States. There is sassafras though, a wood that has always intrigued me. A bit tougher than Paulownia, but still a weakling according to the The Wood Database strength index, this North American hardwood is not common but, if you can find it, the lumber is also not particularly expensive. I got 20 board-feet from the nice selection available at Reader’s Hardwood Supply. The hinges and other hardware for the cabinet will be selected later, once I can assess the character of the piece.

Sassafras boards

Dimensioning

To begin, I went back and studied the blog post for the Korean Stand to refresh my memory on its production. Not much has changed in the workshop since then and so I set about on that same path, replacing red oak with sassafras. If you have never worked with sassafras I suggest you give it a try. It smells so sweet at the saw, cuts like warm butter and stays “true” when ripped into thin poles. Fashioning the frame parts for this piece is all about ripping these rectangular poles at the table saw: all 7/8 in. wide and either 7/8 or 1/2 in. in the depth dimension. Ripping narrow slices, such as the 1/2 in. thick rails required for this piece (n = 14), can be tricky and I found that my homemade “straddle fence push tool” worked great to cut accurate parts, safely.

Ripping 1/2 in. wide rails at the table saw

After all the leg poles and rails were cut-out and trimmed to final length, I needed to assign them each a “role” and then fashion the mortises, tenons and grooves for the joinery. These operations variously employed the mortiser, miter saw, table saw, and router table, as well as a Sharpie for labeling what’s what. When complete, 22 value-added parts had been produced.

22 Frame parts

After some fine-tuning at the joints, the parts could be metamorphosed into a frame.

Dry-fit frame

The next step involved re-sawing sassafras boards to make the three shelf and four side panel parts. I decided to use birch plywood for the (out of sight) cabinet floor and drawer support layers. Each sassafras shelf/panel would be comprised of three narrow boards glued together - a result of the plank widths available at the lumberyard. Fortunately, the three shelves for this piece could be fashioned out of a single plank, thereby ensuring consistency of color and grain. After chopping that plank into four segments of approximate final length, the boards were re-sawn at the band saw into thinner parts which then were all thickness planed to a depth that snuggly fit the rail grooves, ~1/4 in. To create the 14 1/2 in. square shelves, a 2 1/2 in. wide board would be sandwiched in between two 6 in. boards. Attention to grain pattern and direction helped to create visually pleasing shelves that were also warp-resistant. The components were glued together and the resulting shelves trimmed to their final dimensions using a combination of track saw and table saw. Small notches were made at all the corners to accommodate the frame poles. The side panels were constructed in a like manner, whereas, the plywood layers were fashioned from 1/2 in. material by rabbeting along the sides to make “tongues” to fit the grooved rails.

Glueing 3 boards together to make a side panel

After some easing of the edges with a hand plane, the panel parts were dry-fit with the poles and rails. This serves to stiffen the structure and gives a first glimpse of the final form.

Dry-fit frame with panels

Two final case parts were fashioned to serve as hinge boards along the sides of the doored cavity. These were rabbeted so that the front edge would fit within a groove on the side poles, thus recessing the door frame the same amount (1/8 in.) as the side panels. With that completed, the parts were disassembled and all surfaces card-scraped and sanded to #220 grit. The last step before glueing-up the carcass was to liberate the tenons at the bottom of the poles. The tenons will join to the tatami-zuri boards later in the build and their positions were marked with grooves at the very beginning.

Assembly and Finish

There is still much to be built, but it was now time to pause and assemble the carcass. The first step is to decide on the final finish and whether this would require treating the panels prior to glue-up or not. I have come to favor simple oil finishes that let the wood glory in natural hues. However, I found that when surfacing my yellow-brown sassafras to a final state, a dreary gray chatoyance was produced that made the panel boards look “dirty”. Further, I found that oil finishes on a scrap piece did not “clean” things up. This odd coloration might change as the boards age, or it might not. Thus, it was worth experimenting with some colored finishes to improve the look. I liked the orange-brown color of the exemplar piece and so I aimed in that direction.

A variety of dyes, glazes and stains were tested with the goal of imparting a better “look” while not going overboard. I picked among the products that I already owned, and after a few days of play landed on a nice ZAR® stain by the name of “Salem Maple” (Red Top Translate: “reddish brown”). On my scraps it seemed to bring the grain to the fore while imparting a more uniform background red that worked better with gray. Sold! I would also wait until the very end of the build to stain and varnish the piece.

Finishing test panels

*Oil-only (note gray tones)

‡ Salem Maple stain “winner”

Assembly of the carcass was a smooth operation given the prior labelling of parts and some assistance from Joung. I’ve hit upon a favored sequence for these cabinet builds: assemble the back flat on the workbench; then raise the sides; and finally cap-off the front before standing the thing upright to cure.

Carcass with glue and clamps applied

Next came the doors. These are simple framed panel doors that I chose to make even simpler. You might have noticed on the exemplar that the interior edge of the door’s stiles and rails had been eased to create a “rounded” rectangular opening for the panel. It is a subtle way of softening the look which adds appeal. I tried to reproduce this on some practice parts, but all of my attempts were unsatisfactory. In the end, I made two rectangular doors and a vow to keep noodling on how to create the rounded version next time.

Mitered panel doors

Let’s talk hardware. Alas, procuring traditional Korean furniture hardware is a challenge in the 21st century. Over time, I have accumulated a small assortment of these treasures, almost exclusively in black, mimicking the iron fittings used for kitchen cabinets, trunks and such. The brass stuff is very hard to find, but that is the material I wanted for this piece. What I did find was a Chinese-inspired latch in antique brass from an Etsy merchant (FashionLook4U) that might look nice to anchor the cabinet portion. What I could not find was a suitable surface mounted hinge set in antique brass to match. Rather than resort to a mis-match that would distract from the latch, I went with non-mortise butt hinges, where only the barrels would be visible. As to the drawer, I wanted it to be a secret so no hardware was required here, just a spring-loaded drawer kicker with a mechanism akin to that of a retractable ball point pen. The hinges and kicker were obtained from Lee Valley Tools, a nice Canadian firm.

Door and drawer hardware

Before completing the drawer and doors I needed to finish up the base. A decorative punghyeol or “ventilation cutout” was constructed by joining 3 thin pieces with miters and slipping them into grooves on the legs and rail. Next, two tatami-zuri boards were fashioned from straight-grained stock, with mortises cut at each end for the joinery. These slipped around those tenons at the end of the leg poles to form the characteristic “feet” of East Asian furniture.

Tatami-zuri and mitered punghyeol trim in place

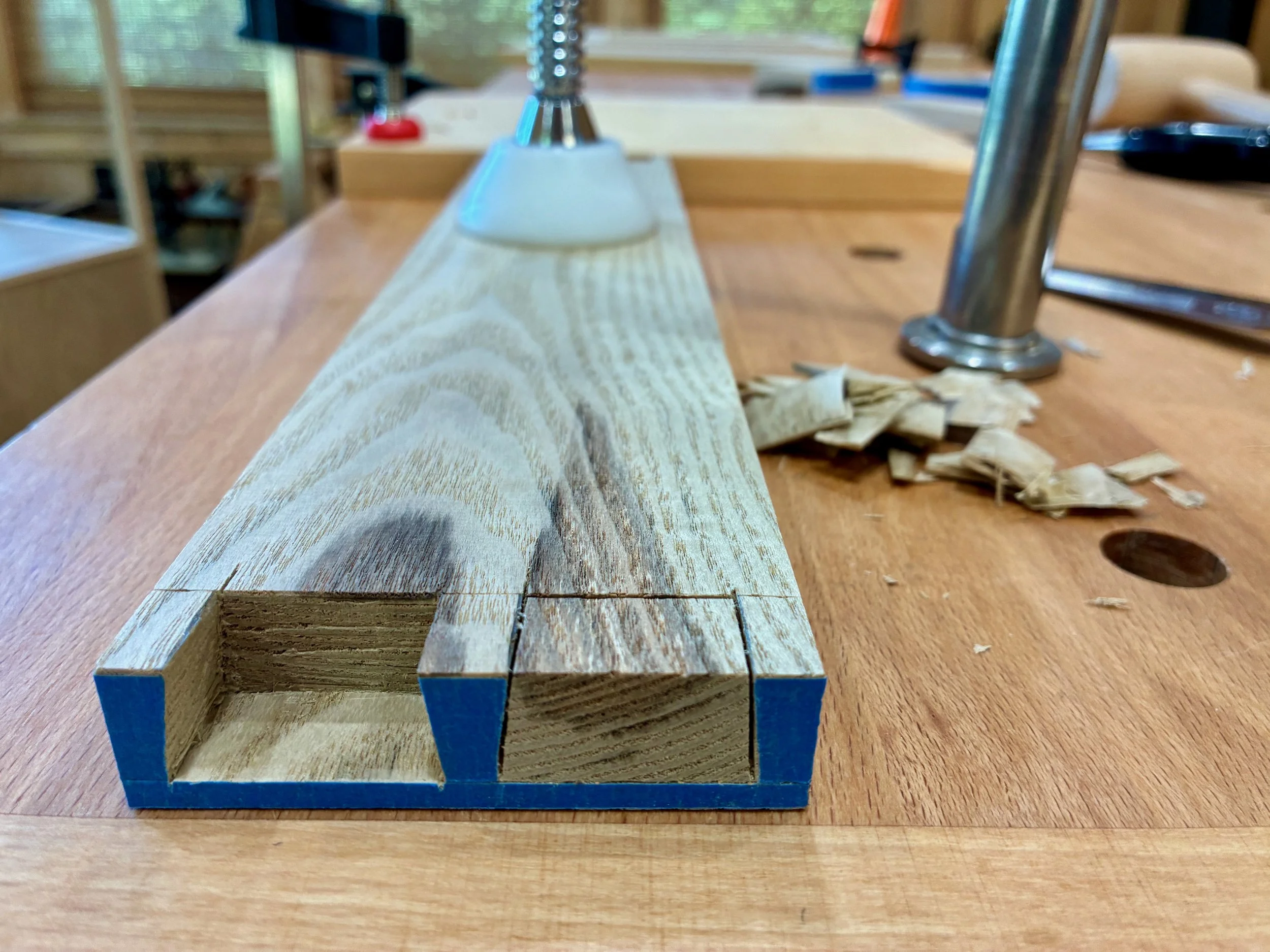

Time to tackle the drawer. Since the original was drawerless, I would be co-opting the space below the doors for this feature. An inset drawer here would be nearly indistinguishable from the original, yet provide useful space for knitting needle storage. This slim, 3 inch drawer would be constructed using half-blind dovetails in front and lock joints for the back. A thin plywood board would be used for the bottom to maximize cavity height. After choosing the best grain from the remaining stock, the drawer front was cut to exact dimensions and then the sides were cut to a matching height from less-distinguished sassafras. Once the boards were marked I used my new dovetail saw to cut the joint elements. Sassafras is a soft wood to saw and chisel, making this an easy maiden voyage and one of my better dovetail experiences.

Cutting the tails on both side boards taped together

Chiseling pins out of the drawer front

After dadoing slots for the back and bottom, the drawer snapped together nice and neat. Along the sides of the cabinet cavity, two “guide” boards were glued to keep the drawer tucked snug while running in and out. The back board was modified to accept the kicker and then all drawer parts were glued together. Once dry, a hand plane and sandpaper were used to perfect the fit.

Drawer glue-up

Finally, it was time to mount the doors. The first step was to attach the hinges to the hinge boards and then glue those boards in place along the sides of the cavity. As prepared, the doors were a bit too large to squeeze into this opening so I used a run across the jointer to get things “close” and then, with a thin spacer beneath, I did my best to measure, mark and mount the doors. This was tougher than anticipated. I think mortised butt hinges would have made for easier job, but I could not find the right size and color in a non-finial hinge. (They must be out there, I just need to accumulate more sourcing sites.) Anyway, the attached doors were still a bit too wide to close on each other and so a block plane was used to gently shave them to a proper fit.

Carefully trimming the doors

That completes construction. From here, bolt holes for the latch hardware could be marked and then the doors disassembled for drilling and final finish.

Doors and drawer in place.

After a final sandpaper touch-up, the finishing step was a snap. The Salem Maple stain was applied and, after a 24 hour drying period, the toned wood was smoothed using a piece of brown paper grocery bag. I learned this trick from watching the furniture refinisher Thomas Johnson on YouTube. By whatever mechanism (burnishing, maybe?) the rough Kraft paper serves to smooth out the nibs without creating dust, nor risk sanding into the stained surface. This was followed by an application of satin sheen gel polyurethane to protect the surfaces. After a 3-day cure, the piece was rubbed down with a soft cloth and then treated with Howard Feed-N-Wax. The wood now had a nice mellow glow without feeling “over-finished.” The drawer sides and cavity were treated with a stronger furniture wax to promote a smooth glide and then the door hardware and doors were attached to complete the build.

Doors back on and latched

I like the character of this quintessentially Korean piece. It enables our hobbies and ennobles our room.

Three Story Table

Crafty Cornice

You probably have never seen the words Craftsman and cornice appearing side-by-side, but that pairing accurately describes my latest Project and I never pass up an opportunity to alliterate! Please read on.

Our home is a pleasant 1951 ranch with unremarkable interior features, save for a fieldstone fireplace and expansive windows. As far as decoration, the trim is a mix of period, so-called “clam shell”, moulding around the doors and “square” casings for the window openings - all painted white. They fit, and I like the simple lines, but … it’s just that lately I have been on an Arts and Crafts jag and obsessing about ways to nudge our home’s decor backward another 50 years to capture more of a bungalow vibe.

Bungalow living room, designed by Gustav Stickley’s United Crafts guild, from The Craftsman, Vol. II, No. 2, April, 1902

(Note the symmetrical windows beside a dominant fireplace, natural wood trim and paneling.)

I have made some progress. Homemade Craftsman furnishings are steadily replacing their store-bought Colonial kin, and the Asian pieces we have scattered about were already at home in the original bungalows. I feel it is mostly the painted walls and white trim that are holding things back, but a total do over to replace the painted parts with bare oak is out of the question. Painted wood paneling is occasionally seen in “new” bungalows, but I don’t think it would work here, busted up by all of those windows. Perhaps a taste of raw wood along the walls would be enough to recast the mid-century mood to an earlier era, especially if that wood were quarter sawn white oak. It was thinking of a solution along these lines that inspired the Craftsman cornice.

There are four banks of windows in our living room and they all might deserve a Craftsman cornice, but the goal of this Project was to fit out the two windows flanking the fireplace to see whether this manner of adding wood to the decor could satisfy desire.

East wall of the living room

Design

In all of my research I have never seen a cornice in a Craftsman bungalow interior. Never. Let alone one made out of wood. Cornices are generally fabric-covered fixtures, and it seems that wooden cornices are, themselves, rare. The ones I have found online are generally painted but nice. Construction-wise, they are a 3-sided, “partial” box trimmed with moulding. My groundbreaking plan was to make the partial box in a Craftsman style using nice wood, and then not paint it. Genius! Lacking precedent I’m certain there are many ways to get this wrong, but there may also be a way to do it right. I figure I’ll never know until I make one and, while I’m at it, I might as well make two.

The “box” dimensions were easily derived from the window casing, itself. First, I sketched the window bank with those red interior blinds and then, using tracing paper, I played with the overlaying cornice structure. I wanted to keep it as lightweight as possible, and so framed panels were used along the major span instead of the typical full thickness plank. This feature is congruent with Craftsman. The dimensional proportions of the moulding and framing elements to the whole are key for making this design “work”, and to study this relationship I consulted Robert Lang’s indispensable book Shop Drawings for Craftsman Interiors. It was certainly helpful to learn the rules here but, in the final plan, these rules were not strictly kept. I concluded that what I was intending to create was a transitional form somewhere between Craftsman stocky and mid-century svelte. A neo-bungalow piece, perhaps.

Craftsman cornice rough plan

The rough plan pictured above makes it difficult to see the cornice design. Next time I’ll have to change the pencil color, but one can imagine that it would look okay. Assuming I could come up with a joinery scheme, the remaining variables were the extent of overhang, and whether the two panels should be broken-up further along their span; and, if I were to do that, whether this would necessitate shifting the grain orientation by 90°. It’s all aesthetics for, unlike furniture, there are few structural fitness concerns here. Rather than build mock-ups, I figured I would just make the pieces to dry-fit, and then further modify them prior to actual assembly should the design require improvement. It’s only wood. (Shush!)

Materials

I had a couple 4/4 quarter sawn white oak boards lying about the shop that should work nicely for the body of both cornices, but I would need to pick up another board to complete the top trim. Onward!

4/4 white oak boards in the rough

Dimensioning

Work started by preparing the bigger of the two boards to fashion the top and bottom rails. Given constraints in the shop, I can maximally accommodate a 73 1/2 in. long board at my jointer and so the plank was chopped to that length, flattened on one edge at the jointer and then ripped into two thinner boards at the table saw. To maintain grain and color consistency within each cornice, these were marked with Sharpies, red and black, and kept segregated during subsequent processing. These boards were flattened on one side at the jointer and then thickness planed to 3/4 in. Next, they were ripped in two again to achieve their 1 3/4 in. final widths. The side and central stiles were fashioned in a like manner to provide 10 frame parts. Finally, a 5/16 in. wide groove was dadoed along the edges at a depth of 3/8 in. These slots would hold the panels and stiles.

Ten slotted frame members

At this point, all members were cut to their final lengths and then 3/8 in. tenons were fashioned on both ends of the six stile parts using a dado blade and cross-cut sled at the table saw. After some fine-tuning with the shoulder plane, the parts could be dry fit together to get a first glimpse of the final form.

Dry-fit frames on top the rough cut panel board

Things were coming together well to this point, and I liked the overall proportions of the cornice front. The next step was to fashion 4 panels from that nicely figured smaller board. To begin, the board was chopped in half, and the two pieces jointed on edge and then ripped to rough width at the table saw. These were then smoothed somewhat on the thickness planer before being re-sawn at the band saw and the resulting 4 pieces thickness planed (for real) to a 5/16 in. depth. Trimming the lengths and widths to their final dimensions allowed for a complete dry fit. I like the way the medullary rays flow in those extended panels so I decided not to break things up further with additional stiles.

Piecing things together

All that remained was to fashion the side “faces” and the top trim from some more white oak. For this I visited a new lumber source, Reader’s Hardwood Supply, located about an hour away in East Taunton, MA. This yard has an excellent mix of species for sale, nicely laid out in racks, and I spent some time picking through their 4/4 quarter sawn white oak section in search of their “cleanest dirty” board. You see, I needed the edge side of this plank to supply the visible portion of that top trim and, as I have griped about in earlier posts, the edge grain of quarter sawn oak boards can range from unsightly to downright ugly. (While I have made my peace with quarter sawn behaviors, unsuspecting visitors would need to look at a 77 inch stretch of this mess at the top of each cornice.) I also took a peek at the plain sawn boards but determined their edge grain was too “wavy”. Then I happened upon a pile of rift sawn white oak. This rare cut, possessing grain at a ~ 45° angle to the board plane, had just the strait-laced edge character I was looking for.

Rift sawn oak diamond in the rough

Because of the uninterrupted length of the top trim, I couldn’t use my jointer to flatten this part without a major disruption to the footprint of the shop and so I worked without that tool. To achieve a straight edge I first screwed an auxiliary board atop my oak and used its straight edge against the table saw fence to rip a correspondingly straight side for the trim. It may not be dead true & square, but close enough for trim work.

Ripping a nice, straight edge while the jointer stands idle (right).

From here, the board could be ripped into two, 1 3/4 in. wide strips which were then thickness planed to a 7/8 in. depth. Shorter sections of that same board were likewise processed to provide the four side trim pieces. While these would ride atop the framed panel body, I needed to achieve a uniform 1/2 in. overhang along that span and so a shallow groove was dadoed on the underside of all trim pieces allowing them to snap into perfect formation during assembly.

Trim pieces with their undersides slotted

Finally, I found a couple white oak scraps with stretches of acceptable looking edge grain that could be milled to the proper dimensions for the side faces, two per cornice. As with the trim, these were slotted to straddle the stile edges to achieve a uniform (1/8 in.) overlap in front.

Assembly and Finish

The parts were all given their final surface preparation and then the four panels were treated with their first course of boiled linseed oil. Assembly was easy. First, the center stile was glued and clamped to the bottom rail and then the panels were slid into place (unglued), capped-off by the end stiles. After adjusting for squareness the top rail was tapped into place and the whole thing clamped to cure. Once dry, a second cornice front was put together in the same fashion.

Putting the panels together

From here the sides were attached with glue, flush at the top but 1/8 of an inch proud on the fronts and bottoms. This little overhang adds extra dimension with shadow lines and makes it look more “finished”, to me. Pocket screws into the top and bottom rails were used to keep this corner solidly at 90°.

Pocket screws on the backside further secure the side faces to the frame

Finally, it was time to apply the trim. I decided to miter the corners, keeping the “look” in line with Craftsman moulding doctrine. The small side trims were cut to a 45° angle and dry-fitted first, and this allowed for accurate marking of the intervening long trim section. After cutting this piece to length a bit of chisel work was needed to widen the slots on each end to accommodate the overhanging sides. With a clean fit assured, the trim sections were glued and clamped.

Gluing the top trim in place

Once fully assembled, the cornices were given two treatments of boiled linseed oil to darken the colors and bring out the contrast of rays versus grain. From here most furniture pieces would proceed right to their photo shoot, but cornices require installation.

I had several fabric covered cornices at my prior house and seem to recall they merely “sat” on L-brackets fastened alongside the window trim. Although my new cornices are twice as large and more than twice as heavy, that was the plan here, too. I secured some 4 in. x 2 in. L-brackets online that I mounted at the ends of the window trim with the short arm protruding. Installation was simply a matter of settling the cornice onto these brackets and letting the weight be supported by the backside of the trim. That trim serves to make the piece a bit top heavy and so to keep the cornice from lurching forward, I used zip ties to cinch the bracket to eye screws mounted in the trim. All seems well.

Cornice mounting scheme

And that’s the story of the Craftsman cornice. They now hang, solemn yet friendly, beside the fireplace stone. I think they do their job but will want to check again after a few months. If they continue to please, I’ll likely whip up a couple variants for the remaining windows of our neo-bungalow living room.

Craftsman cornices

Walker’s Cabinet

“A place for everything and everything in its place.”

– Benjamin Franklin (among others)

Biologists refer to it as “exaptation” when a particular feature of an organism assumes a new function over time. The term was introduced in 1982 by paleontologists Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth Vrba, and was meant to account for evolutionary changes not derived from conventional “adaptation”. Feathers (heat regulation → flight) and the swim bladder (respiration → buoyancy) are popular examples. I have even seen this term applied to inanimate objects such as wheels (locomotion → machine components), but never furniture, although it could. These are the questions that tickle academics and their ilk.

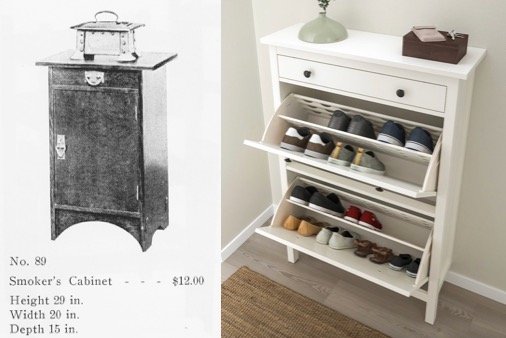

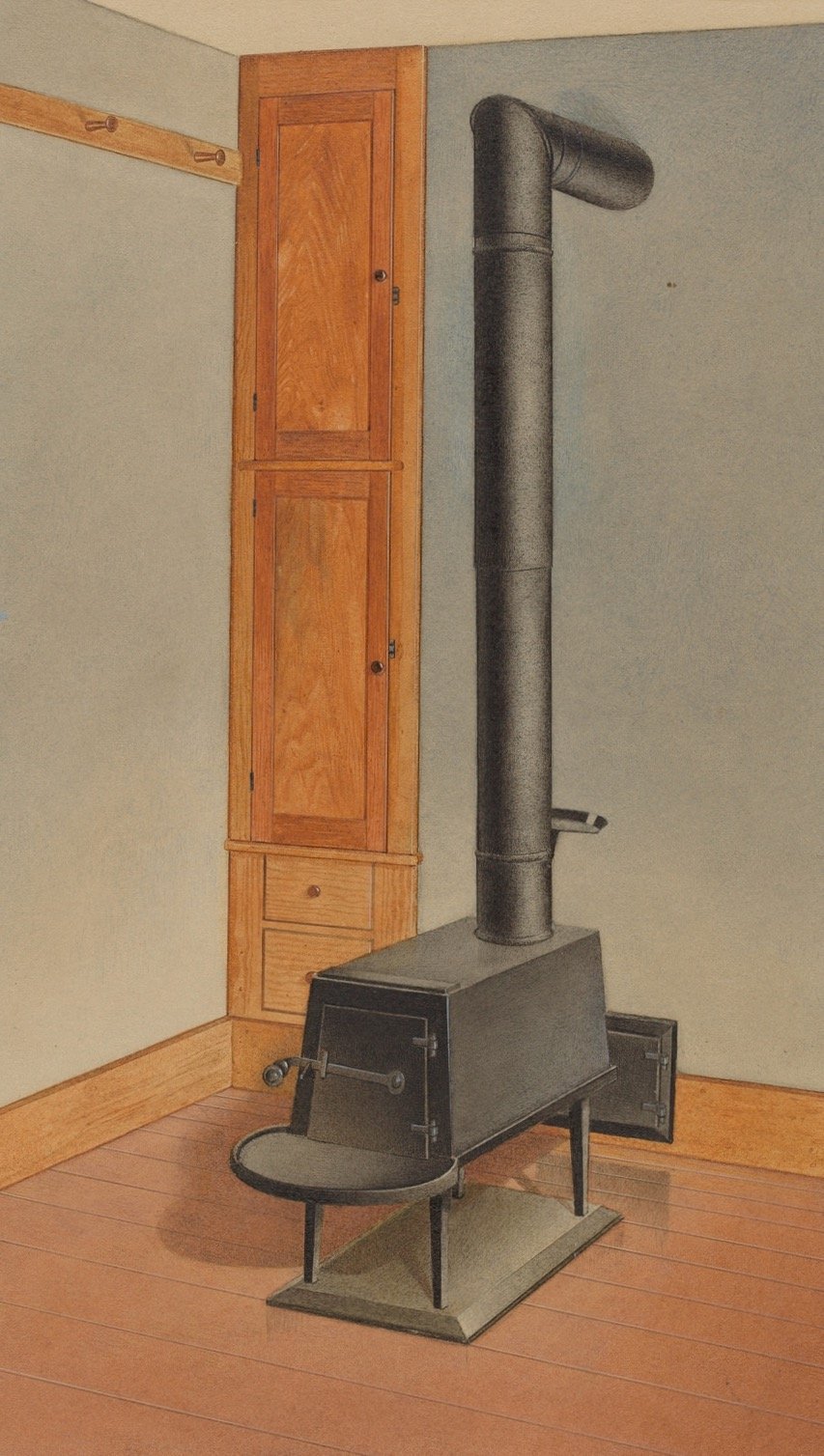

I believe the current Project counts as an “exaptation”. It is a repurposing of those specialized early twentieth century cabinets (e.g., Smoker’s Cabinet) to serve the modern function of footware storage - what we will call a “Walker’s Cabinet”. Largely extinct today, purpose-built cupboards such as the Smoker’s Cabinet were once popular, well-made furniture pieces designed to store items valued by their owners, in this case pipes and tobacco products. Other cabinets were produced specifically for piano sheet music (Music Cabinet), phonograph cylinders (Record Cabinet), dinnerware (China Cabinet); and more. Our cabinet will store the shoes and boots used by walkers; a function not even dreamed of 100 years ago when, at least in America, the few shoes owned were generally worn both indoors and out. It will retain external proportions similar to those earlier pieces but include suitably-spaced shelves on the interior. Of course, products to keep shoes do exist today, and some of these are made of wood. They tend to be either open, cubby-holed structures or possess doors on drop-down hinges, evolutionarily distant from the smoker’s cabinet.

Smoker’s cabinet listed in Gustav Stickley’s 1910 furniture catalog alongside a modern day shoe cabinet of similar proportions

The Walker’s Cabinet is a commission from my brother-in-law, Brooks, as a gift for his wife, my sister Kathy. I have long wanted to build something special for her and now I have the opportunity. In their cozy home they have a spot next to the door that is used for shoe storage, and this piece is intended to replace the existing open shelf unit there. My mission: make it nice.

Design

I was introduced to the Smoker’s Cabinet by way of Gustav Stickley’s 1910 Craftsman furniture catalog piece No. 89 (shown above) but intend to use an item found in his other publication as inspiration for this Project. In addition to furniture catalogs, Stickley produced a magazine, The Craftsman, from 1901 to 1916 that he described as: “An illustrated monthly magazine in the interest of better art, better work and a better more reasonable way of living." Hard to argue with that mission. Adopting, and then adapting, tenets of the British Arts and Crafts movement, Stickley and other writers in The Craftsman worked to open the eyes of a rapidly mechanizing America to the enduring value of craftsmanship and honest work. Even today, these insightful articles retain their punch. Many issues contained a feature article titled: Home Training in Cabinet Work, in which the plans and some helpful hints for building useful furniture pieces were described. Stickley’s intention was for his readers to make some of their own furnishings and, thereby, come to appreciate the pleasure of handicraft. Not the best for business you might reckon, but Stickley, like the other Arts and Crafts leaders, dealt in ideals as well as chattel. In the August, 1907 issue the plans for a Phonograph Stand and Record Cabinet were published. I prefer the style of this one-door cabinet to the Smoker’s version and will use it as the starting point for the Walker’s Cabinet.

Record Cabinet plans, reproduced from The Craftsman, Vol. XII, No. 5, 1907. pp. 562-563.

Rough plans for our cabinet were derived from the Stickley drawing. However, to fit the intended space, the piece would be made narrower and a bit taller. Also, the door swing would be reversed to best accommodate the setting, and the phonograph stand eliminated, too, but all other features would be faithfully maintained (ha!). Such are the perquisites of custom-made furnishings. Two adjustable shelves would be contained within.

Walker’s Cabinet rough plan

Materials

Quarter sawn white oak would be the wood used for this Stickley inspired cabinet, of course. A nice 6/4 and some 4/4 boards were procured from Highland Hardwoods. The hinges and a knob would be selected later, as the piece came together.

Marked-up oak

Dimensioning

To get started, the post-like legs were cut from that hefty 6/4 board. In the end they will be 1 1/4 in. square, but it will take a bit of work to get there. The goal is to have two adjacent and exposed sides of each leg feature that charismatic quarter sawn “look”, formed by the interaction of oak’s coarse grain with the delicate medullary rays exposed by this lumber mill cut. And to achieve that goal it was decided to veneer a thin strip of this so-called “face grain” onto the homely “edge grain” for one side of each post. Stickley, himself, often employed this method for improving upon Nature. Thus, the cross-section of our initial posts would be ~1 1/4 in. x ~1 1/8 in. After applying a thin face grain veneer, cut at the band saw, the proud edges could be hand planed and then the entire pole thickness planed to a uniformly square 1 1/4 in. dimension.

Glueing veneer onto a leg while the other parts wait their turn

With the legs in shape they could be trimmed to final height (36 in.) and then marked as to their final position (Left/Front, etc). These could now be modified with stopped dado grooves to hold the stiles of the frame. The front legs get one groove each, while the backs get two. To begin, a 3/8 in. square mortise was cut at all termini and then a 3/8 in. deep groove was plowed in between at the router table. Finally, at the ends of each groove, deeper sockets were mortised to receive the rail parts.

Cutting mortises within the grooves

Next, the various frame and panel parts were prepped from those 4/4 boards, 23 in all. I have to say that shaping white oak boards, first the smell, then the feel and finally a glimpse of newly planed grain, can be a transcendental experience. It never gets old. The process goes like this: 1. prepare a board flat & square; 2. thickness plane to a uniform dimension (in this case either 3/4 or 5/8 in.); 3. cut to final length and width; 4. fashion the joint element (mortise or tenon) using power tools; 5. refine the joining parts using hand tools for a snug fit - all while correcting mistakes as you go. The first steps are done in batches to assure dimensional uniformity for the parts that fit next to each other, whereas the final hand work is done joint-by-joint. This is woodworking and, much like any sport, it contains enough variety with endless opportunities for improvement to keep the committed coming back for more.

That’s enough pre-game, here are a few memorable shots from the event.

Bench scene during the joint work

One of many dry-fits

Creating a template for the arched rail

Drilling holes for the adjustable shelves

Edging the plywood floor board with white oak

All parts smoothed and ready for assembly

Assembly and Finish

After giving the panels their first treatment of boiled linseed oil finish, the whole thing was glued-up and clamped. For this piece, all 32 cabinet parts would be put together in a single act and so I decided to use Titebond’s Genuine Hide Glue for the early joints. Back in Stickley’s day, hide glue was the only useful adhesive for wood. We now have a host of options but I chose this product for its extended “open” time, making the glue-up easier to get right. To begin, the back section was assembled, flat on the workbench. The cabinet top and bottom were then slotted into place, followed by the underlying rails, and from there the two side sections could be constructed, piece-by-piece. The final steps were to attach the front leg poles and arched rail, and for this I used the stronger Titebond III adhesive. Once hammered tight and clamped, the hefty cabinet was lowered to the floor to be sure that all four legs could touch at the same time, and then left to cure in that position. This was a full 30 minute operation, helped tremendously by my wife, Joung’s, participation. Once the case was cured and sanded, the oak edge pieces were applied to the floor using biscuits.

Cabinet glue-up (note biscuit slots for the front floor edge)

With the cavity’s opening now defined, the door could be fashioned using the same tenoned-rail and stile method as the cabinet frame. With every build, the sequence of cuts to construct a 5-part, framed panel door becomes a smoother production. But this efficiency does nothing to subtract from the joy.

Door frame glued-up around an oiled panel

The door hardware was procured online from a nicely run hardware business, Hardwick & Sons: ball tipped hinges and a Craftsman style drop pull. These designs, in a copper finish, are very close to the Stickley originals.

Door hardware