Repeat Costumers

Back in 2022 I made a simple furnishing for myself that I’ve appreciated every day thereafter, a costumer. This sturdy partner helps to keep that area around my dresser tidy, and glancing at its form, a dutiful marriage of cherry and brass, can put a smile on my face to boot. Witness the power of furniture! For Christmas this year my wife and I decided that our sons would enjoy the gift of costumer ownership, too.

Design

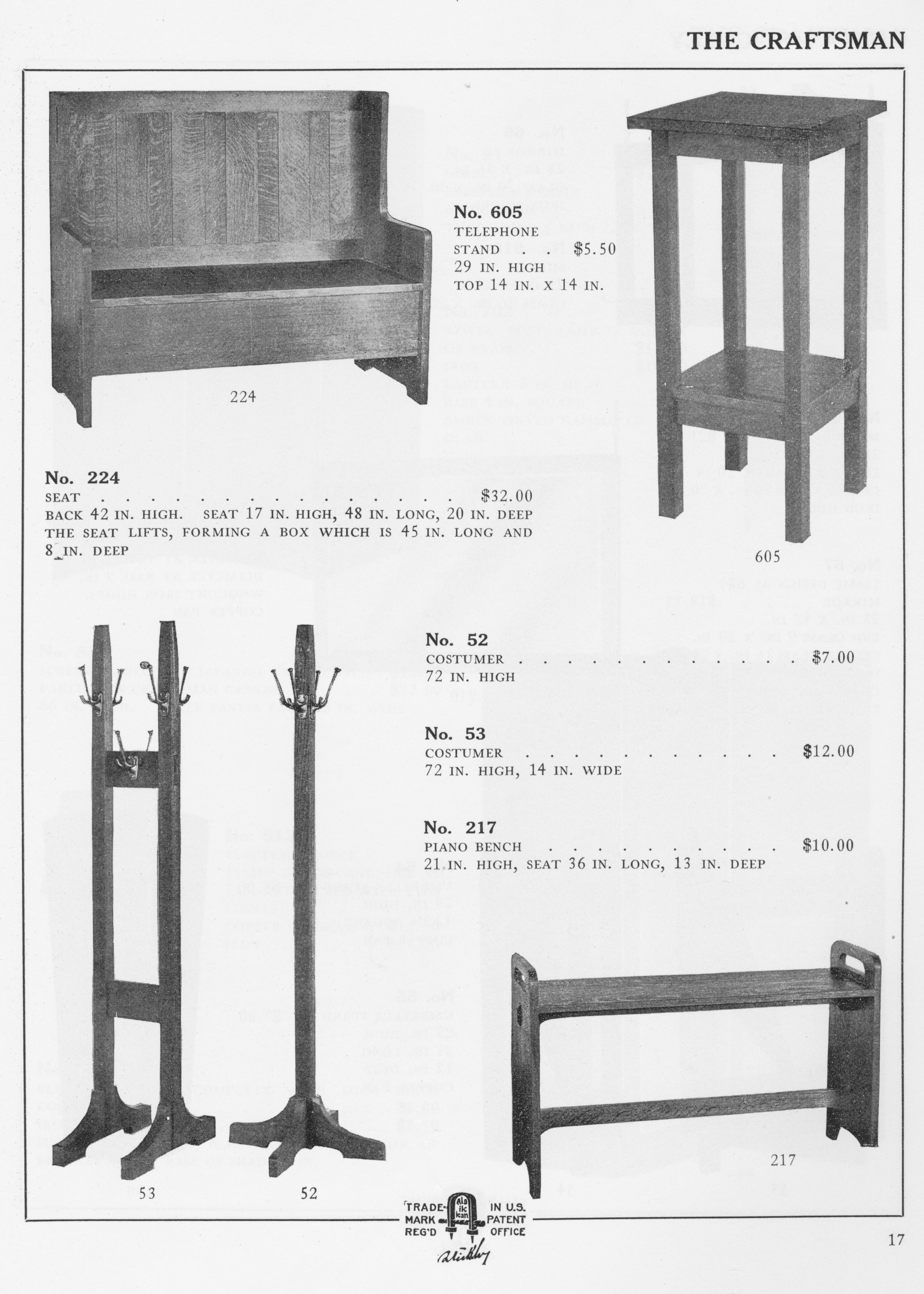

I love the mission-style of my costumer, the plans for which were found in a 1917 Middle School wood shop manual, and I even saved the pattern jig used for shaping the leg braces thinking it would come in handy again some day. However, I have yet to re-make any of my Projects and this would not be the one. These costumers would be variants of the form. Though not a popular item today, if you dig back a hundred years you can find many costumer examples. This makes one wonder why the demand for this useful item ever petered out? I blame walk-in closets and washing machines. Anyway, I found a couple of distinguished specimens among Gustav Stickley’s 1912 catalog offerings and decided to give them a try.

from: Craftsman Furniture, April 1912, p.17.

found in: The 1912 and 1915 Gustav Stickley Craftsman Furniture Catalogs, Dover: New York, 1991.

As far as woodworking goes, the feet represent the only challenge here and with no physical construction plan I was left guessing at the joinery used to fasten them to the pole. My hunches were either mortise and tenon (Gustav’s “go to” joint) or else dowels. Then I had the idea to search online auction sites for “Stickley costumers” and the potential to get a closer look at genuine examples. This proved eye-opening. First, that $12 double costumer (No. 53) now sells for well over $1,000 as an antique. And second, the feet are mated to the pole using a T-bridle joint. That joint makes sense, although I would never have come up with it on my own. The feet “pads” also appear to be attached with wooden dowels. Hunh! Learn something new every day.

No. 53’s underside as glimpsed on eBay

As for No. 52, I could not find a recent auction price nor could I definitively determine the joinery used, which kept mortise and tenon, as well as, dowels in play. Anyway, some good insights on proportions were gained. The internet is a wonderful thing, when used properly.

View of No. 52’s joints from a MutualArt auction listing

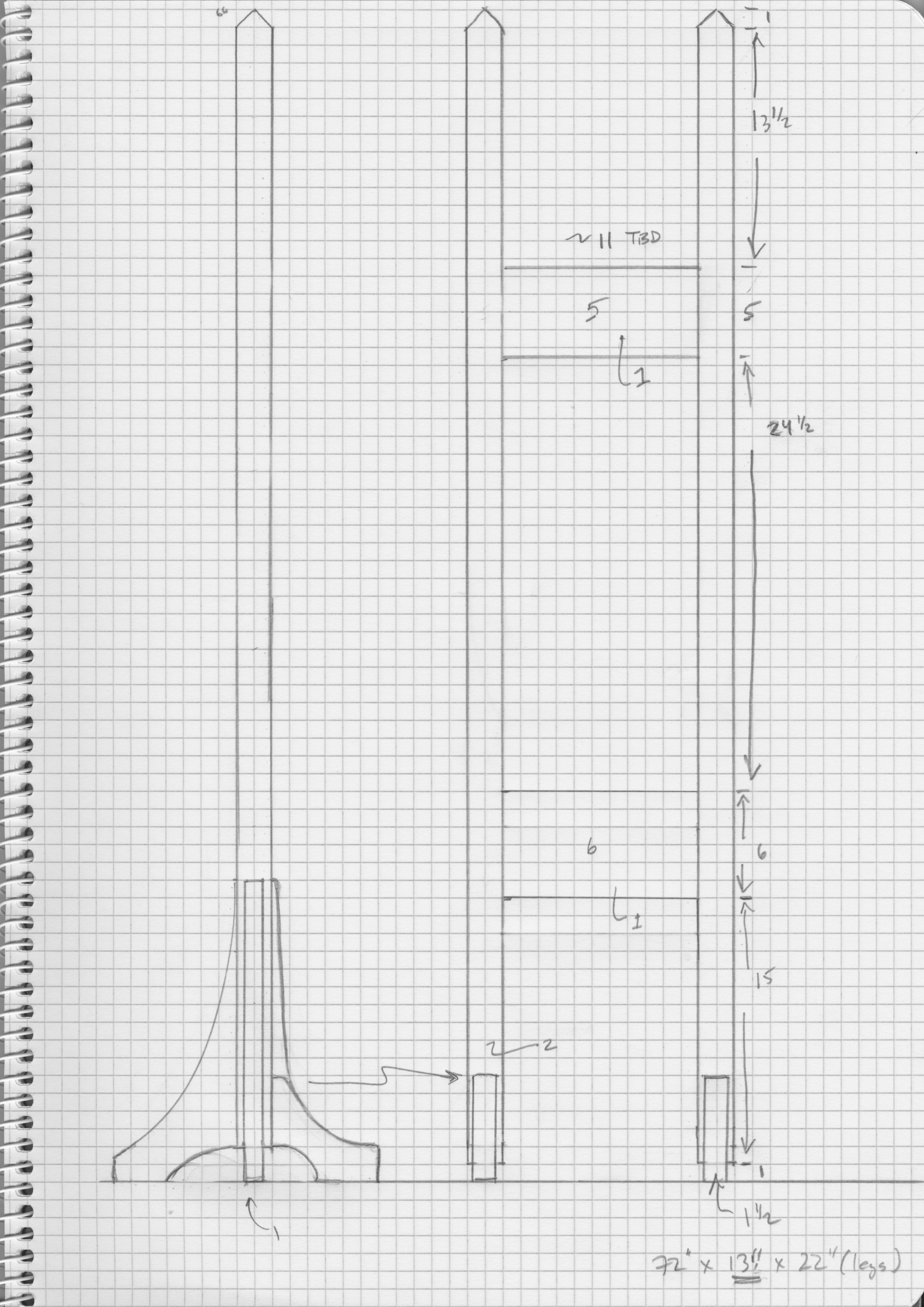

In the end these would be my versions of Nos. 52 and 53, not exact reproductions, but knowing how the originals were made is valuable just the same. A quick sketch, including some possible variations on the No. 52 feet, was all that was necessary to get things started in the workshop.

Costumer plans

Materials

I have yet to find an example of Gustav Stickley costumers made from a wood other than quarter sawn white oak, which is no surprise. However, some contemporaneous L. & J.G. Stickley costumers can be found in cherry and that is the species I was leaning toward for No. 53. It’s a lovely wood to work, and seemed to be the proper choice for son No. 1 and wife. I went with soft maple for No. 52, thinking it could lend a more modern look and knowing that it would blend well with the other custom furnishings built by son No. 2. The planks were purchased at Highland Hardwoods and the hooks for both were procured online from House of Antique Hardware.

5/4 maple and cherry planks

Dimensioning

In principle, making the 2 x 2 inch square poles was straightforward: prep the 5/4 rough lumber to approximately 1 1/16 in. thickness; rip these planks to approximately 2 1/8 in. width; glue two together with attention to matching the grain flow, and then joint/thickness plane the sides to uniformity. In practice, some detours were taken.

No. 53: The four cherry half-poles were diverted mid-process for some dado work that would create the required central mortises upon glue-up. This is a shortcut that I have used on occasion and one most likely not taken in the Stickley shop. Hey, whatever works! I find it easier to let the table saw cut a couple dados than to hump my mortiser bit through two inches of hardwood. Of course, if I had a better mortiser …

Two halves make a “hole” (ha!)

No 52: The maple pole for this one posed a different challenge: color. It happens that the heartwood buried within the center of my soft maple plank was a deep blue-green color, whereas the bulk of the wood shone creamy white. Maple is sometimes like that. At the lumberyard I had convinced myself I could cut around this area with no problem, but in the shop there turned out to be no way of avoiding a green streak in my pole. I glued up the half-poles anyway and then concluded that this was too ugly to proceed. That’s when I realized that one of Gustav’s 125-year old tricks could save the day. As mentioned above, Gustav Stickley worked almost exclusively in quarter sawn white oak; a mill cut which is as beautifully grained on the face side as it is gruesomely streaked on the edge side. In oak, you learn to take the good with the bad. To produce a beautiful, 4-faced pole one can invest the effort to make a so-called “quadralinear” part, as I did for legs on the No. 220 Prairie Settle, or else take a shortcut as Gustav often did by applying a face grain veneer onto the edge sides. In like manner, I decided to cover that green streak with a creamy maple veneer cut from extra material. Only one side of the pole needed remediation, and I’m not crazy about the extra seam lines, but I think it was worth it.

Maple pole before and after cosmetic surgery

With the poles in hand it was now time to work on the feet. While digging into old Craftsman Furniture catalogs I discovered that both the foot shape and hook hardware had changed over time. Feet on Nos. 52 and 53 from the 1909 catalog appear to be thicker and less elegantly curved than the 1912 versions depicted above. Also, hardware on the earlier costumers consisted of two-pronged hooks, whereas, an additional point had been added to every antler by 1912. It would be interesting to learn the intent behind the design evolution here, but, for this Project, I now favored the 1912 style for No. 53, and 1909’s for No. 52.

Costumers from the 1909 Catalogue of Craftsman Furniture.

found in: Gustav Stickley After 1909, TURN of the CENTURY EDITIONS: New York, 1990.

No. 53: Recall, the feet of that double costumer were mounted using a T-bridal joint formed by the insertion of a double footed board into an “open mortise” cut from the pole bottom. I used the band saw to slice (two) 5 inch deep incisions at the base of each pole, and then a hand chisel was employed to remove the remaining waste. This created a 1 in. wide opening for the joint.

Cutting the open mortise

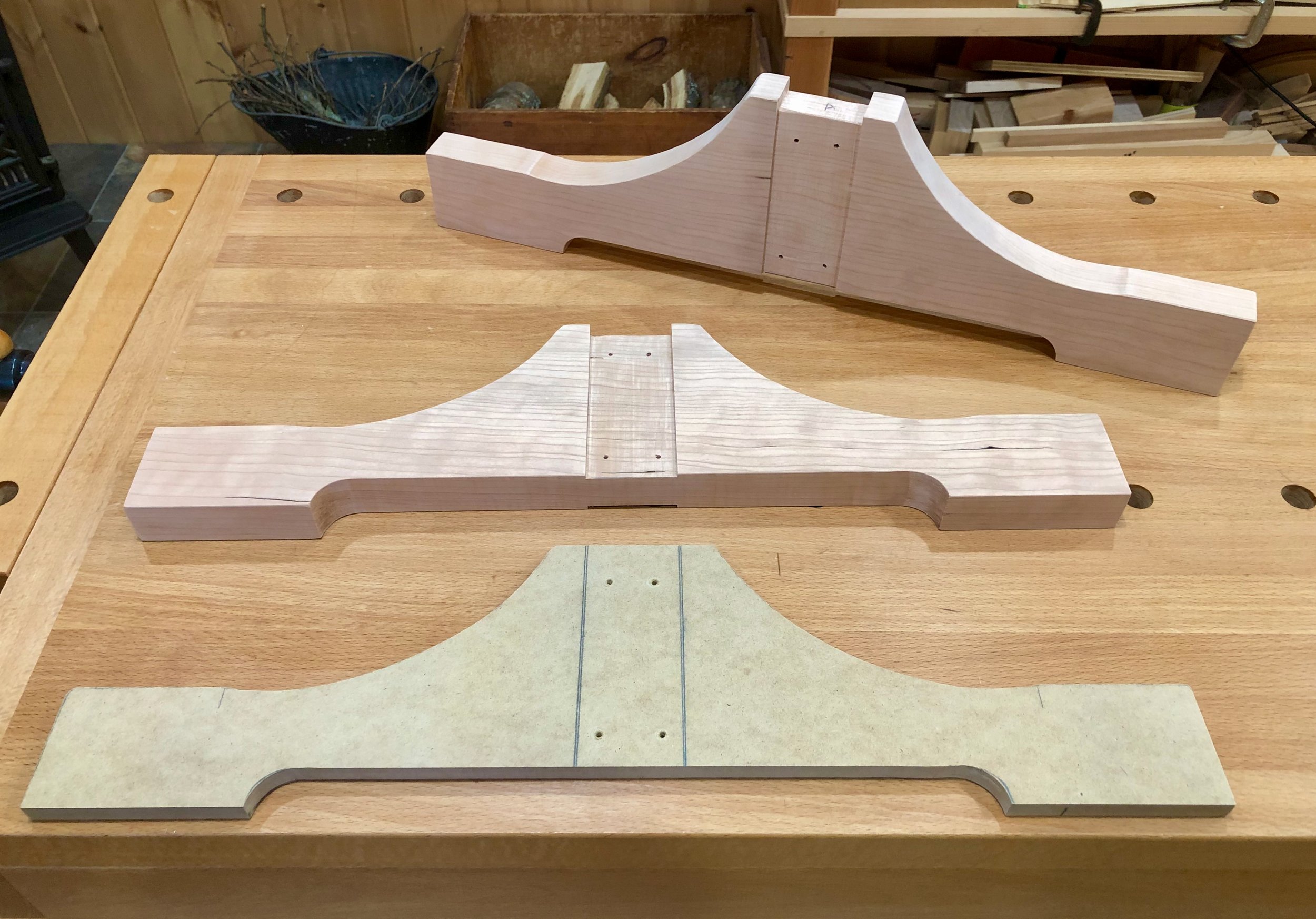

The foot boards were fashioned from 1 1/4 in. thick cherry stock into which a central “waist” was dadoed at the table saw. The waist will fit snugly within that 1 in. mortise opening. Before shaping the feet, a template was prepared from 1/2 in. medium density fiberboard (mdf). This template was used first as a stencil to trace its shape onto the cherry and then the two boards were clamped together so that the pads could be defined by boring holes at the drill press.

Defining the pad edges, two at a time (note void defects visible on the board at lower left)

Following a rough cut of the foot profiles at the band saw, the mdf template was mounted to a cherry foot part with screws, and this now served as a pattern for smoothing at the router table using a flush trim bit. An unfortunate void (cavity) within the cherry wood caused a blowout along one edge, but this could be repaired.

Cherry feet and template

No. 52:

Preparing the feet for No. 52 was more straightforward. A different mdf template was created for these parts and then the same cut-out & smoothing operations were conducted, as above.

Maple feet and template

There was one more thing to do on No. 53 before assembly and that was to create the bridges that join the two poles together. These 5 and 6 in. wide boards are tenoned at both ends to fit within the mortises that were created upon pole formation. I used a quarter sawn cherry board in my possession to make these. To begin, I scored the shoulder cuts at the sliding miter saw to give me the cleanest edges. The bulk from each tenon’s cheek was then hogged-out on the table saw using a dado blade. Manicuring the rough tenons and mortise openings proceeded, one pair at a time, in the bench room using a hand plane and chisel to achieve a snug fit.

Bridges complete

A final sequence of cuts was used to create the peak at the top of every pole. Four slices, each, at the sliding miter saw followed by a little polishing with sandpaper made quick work of this.

Assembly and Finish

After smoothing all parts it was time to put them together. The goal being that the poles stand straight and solid once assembled.

No. 53:

To begin, the bridges were glued into the poles, nice and square. No joint is more satisfyingly steadfast than a trough mortise tenon.

Assembling No. 53’s pole structure

Once cured, the ends of the tenons were cut flush to a spacer board that laid 1/8 inch above the pole surface and then the edges were rounded using a hand plane and sanding block. Next, the two feet parts were glued into place. This makes for a very solid construct, but Stickley chose to also pin his tenons with dowels, and I would do the same. With today’s glues this is undoubtedly overkill, but the decorative effect of that extra fastener is well worth the effort. A couple 5/8 in. diameter cherry pins were pounded-out on a dowel plate and then a simple jig was used to register the hole to be bored at each bridal joint. Dowels of 1/2 in. diameter were made for the bridge joints, and instead of going all the way through I cheated and inserted “half “dowels, one from each side. The structural benefit is the same, but this way I eliminate the potential for blow-out on the back side while drilling. Finally, the dowel ends were cut flush and planed smooth with the poles

Drilling holes for the dowel pins in No 53

No. 52:

For No. 52 I used dowels to attach the feet to the pole. This meant drilling dowel holes into the center of the pole that matched those drilled into the foot parts, and for this I used my handy “Dowl-it” jig. Once the pieces are marked to register the proper height, this jig makes it easy to drill holes into the geometric center of any part. 5/16 in. diameter holes were drilled as required, two per foot.

Have jig, will dowel.

With all the holes in place the feet were attached using store-bought dowels and glue. In theory, the costumer should now stand perfectly upright and stable, but there is a slight wobble to this one which I corrected by applying a thin maple platform to one of the soles.*

* “It’s always something!” - anonymous.

All feet glued into place on No. 52

Now, it was time for the finish. Gel polyurethane was used on both pieces. Two coats, with a gray pad treatment in between, and a good buff at the end did the trick. Of note, the end grain on No. 52’s maple became maroon when hit with the finish, once again revealing some surprising colors in this reputedly boring hardwood. It will be interesting to see the patina that builds over time. After applying my dojang, stamped onto 1 inch dia. maple discs, the last step was to mount the hooks.

No. 53’s T-bridal joint and dojang

Unlike Stickley, I chose to stagger the hook heights on No. 52. It seemed more natural, somehow. I marked the two different heights, drew my square lines in pencil and then mounted the hardware. Everything looked fine until I stood it upright to discover that all the hooks were listing 5° to the right. I had forgot to check that the two mounting holes on the iron hooks were fashioned level with one other during manufacture, and they were not*.

*Ibid.

To correct things, I removed the left screw from each and rotated the hooks out of the way. I then drilled the screw holes wider, filled those voids with 1/8 in. dowels, re-drilled new holes at the proper positions, and remounted the hooks. Only one screw head was sheared off in the process.*

*Ibid !

Re-mounting the hooks on No. 52

In contrast, the hooks for No. 53 were attached without issue. Mounting the back-to-back hooks on that one inch thick bridge was accomplished by slightly staggering their vertical positions. This was to obey the Pauli Exclusion Principle as it applies to screws.

Hooks on No. 53

And that’s a wrap. Two rough boards and some iron used to create useful furnishings and a story. In addition, enjoyable memories were created along the way. Merry Christmas boys!

Nos. 52 and 53 in 2024