Tickin’ Francese

An Ansonia Clock Co. advertisement (c. 1900)

Get it? Tickin’ Francese? Oh, but I do crack myself up! Which is a good thing too, for sometimes I’d swear I am the only person who appreciates my Dad puns (heh, heh … wait …). Anyway, this post is about the Americanization of a classic French entrée clock.

In addition to the dozen or so clocks scattered about the house and workshop that tell time I also have a small collection of antique clocks that tell stories. These wonderful objects, five in total, were collected over the past quarter century as my interest in clocks developed. Four of the five are operational and while they all have special meaning for me, no clock in my collection would be particularly valuable to anyone other than me. My favorite, a late nineteenth century French marble clock, has been keeping our living room on time for the past 18 years. I recently did some digging into the history of that French clock and, like most research efforts, this revealed some unexpected insights.

French marble clock with Abraham Lincoln, a contemporary.

While it is easy (and fun) to study the general subject of “time keeping”, researching clock devices in any depth is more of a challenge. Books on clocks tend to be either pictorial encyclopedias, manufacturer’s sales catalogs or repair manuals. A few general histories are out there, and I found Eric Bruton’s The History of Clocks and Watches to be a delightfully informative reference. But to dig deep into any particular clock the internet is probably the best option; spade that turf long enough and one can accumulate a good pile of consistent-ish information. There are also a few clock repair gurus on YouTube who share their knowledge of these once indispensable, now venerable relics with loving zeal (kinda like that high school Latin teacher) and I invite you to check out Time4clocks as an example. Those are my sources for the following tale.

The plot line is a comparison of clock cases, but the story begins with a desire to understand the history of my particular French marble clock, and for that we need to examine the clock works. That is where the maker and date can be established. Of the many clockmakers producing the distinctive pendule de Paris (clock of Paris) movements in nineteenth century France, mine was made by the most prolific: Japy Frères et Cie (Japy Brothers & Co.). According to this source, in 1806 the Japy brothers, three sons of the industrial pioneer and clock making giant Édouard Louis Frédéric Japy (1749-1812), inherited a first of its kind, single site manufacturing operation for clocks and all of their parts. This firm dominated Europe’s clockmaking world for decades before their over-diversification into products such as typewriters and bicycle parts nearly drove them into the ground. During their heyday, however, Japy Frères made a wide variety of strikingly beautiful timepieces, and among these are the family of so-called black marble clocks. Googling that descriptor gives you an idea of the diversity of production for just this one style.

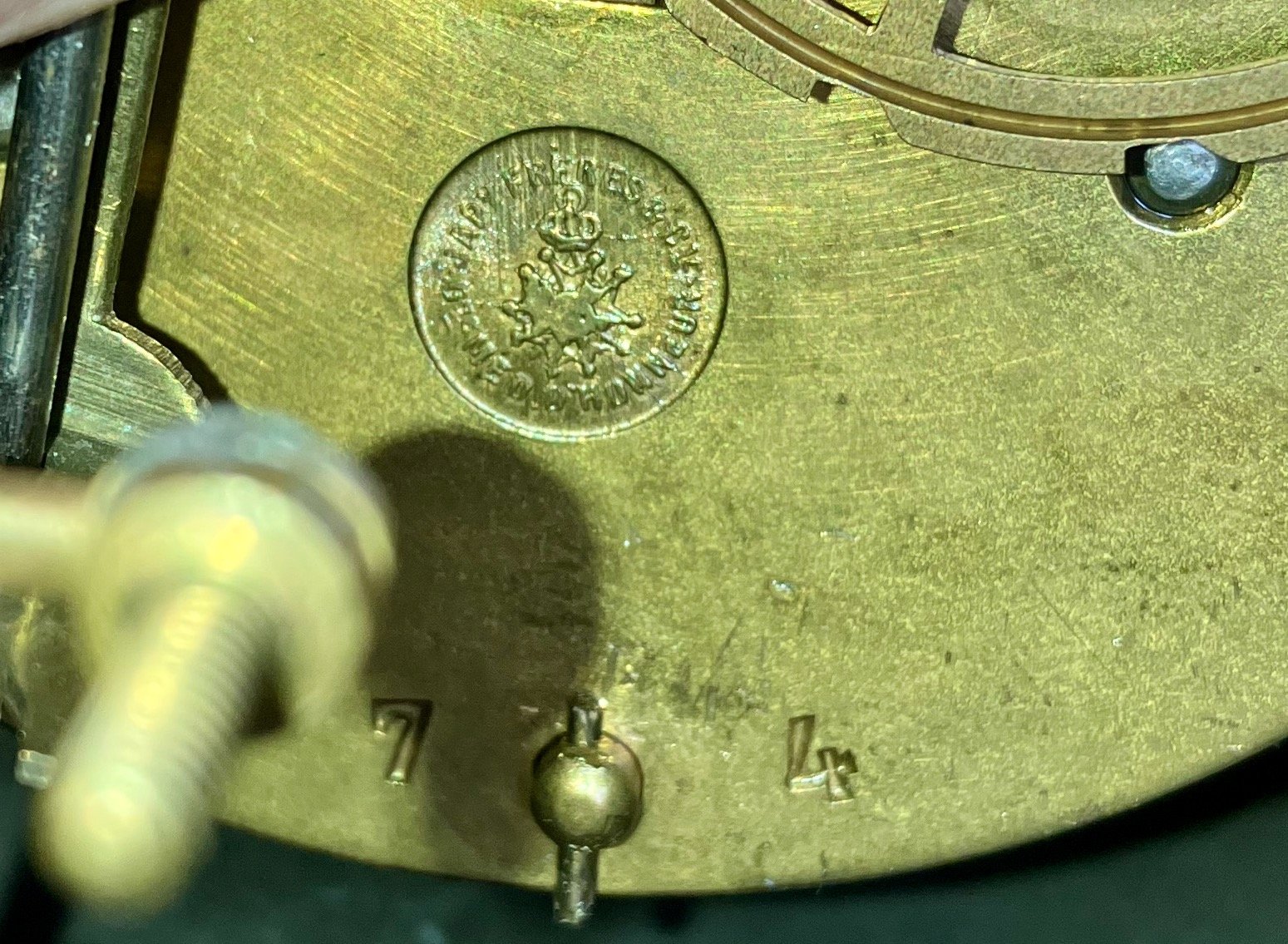

As far as I can tell, my particular specimen dates to the 1890s. This was determined by inspecting the backside of the movement, ignoring those serial number-like red herrings stamped all about, and interpreting the logo that changed over time depending on which new clockmaking award the brothers chose to plug.

‘Clock of Paris’ movement backside (bell and pendulum removed)

Though certain features, such as the Brocot escapement and exposed count wheel, are characteristic of an earlier era the logo on my movement, declaring the “Gde Med. D'Honneur" (Gold Medal of Honor), was apparently used from 1888-1900. However, given the tenuousness of this dating method, my personal language barrier and the general hazards associated with internet sleuthing, it would not surprise me if it is a decade or two older than that.

Logo close up

Black marble clocks were wildly popular in Europe and Great Britain. And as a nation of immigrants with a fondness for Old World tastes, they were sought after in the U.S., too. Somehow my clock made it across the Atlantic and, ultimately, to a clock shop in Hightstown, NJ where I purchased it in 2005. However, most nineteenth century Americans had to make do with the local fare. The so-called black mantle clocks, presumably a welcome diversion from the prevailing brown wooden cases, were top sellers and all of the big U.S. companies had their line-ups (e.g., Ansonia, W.L. Gilbert, Ingraham, New Haven, Sessions, Seth Thomas, Waterbury). And while some companies imported marble for these, most cases were made from substitute materials. To mimic the French stained marble (largely quarried in Belgium, as it turns out) those crafty Americans used a process called “japanning” to put a black enamel coating on either a wood or metal clock case. Seth Thomas also employed an early type of celluloid plastic, called “adamantine”, to veneer a flat black or even a fake, so-called “marbleized” finish to wooden cases. Resourceful!

After learning about my French clock and its influence on contemporaneous American designs it dawned on me that two of my other antique clocks fell into this same family. The first is a stout Ansonia metal clock, also acquired in New Jersey, that graced the mantle of our lake house there for many years. Purchased in 1998, it dates from the 1880s and was one of the many many black mantle clock designs produced by that firm, founded in 1850 by Anson G. Phelps. I had the 100-year old movement cleaned and oiled at that time and it is still running strong. The dial and hands have been replaced over the years, but that is not uncommon for heavily used clocks. On first glance it bears little resemblance to my bone fide marble clock but it does possess the characteristic brass rimmed, flat glass bezel, the telltale botanical engravings and it was, of course, black.

My Ansonia black mantle clock c. 1885

The movement is visible from the backside beneath the circular cover. Like all American varieties the works are less space-efficient than the pendule de Paris, but sturdy.

Ansonia movement, patented June 13, 1882.

For marketing purposes, many clocks were given names and this one, ironically, was called “Unique”. The case turned out to be a close copy of another one of Japy’s marble clocks. In fact, if you invert the top it is a dead ringer - in enameled iron.

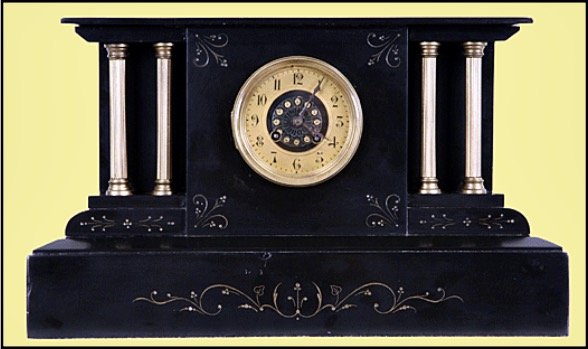

Japy clock c. 1860

(reproduced from liveauctioneers.com website)

The second American black mantle clock in my collection comes via Michigan and my departed Uncle Chuck’s estate. I wish I knew more of its provenance and whether he may have inherited it from an earlier family member but all I can uncover is its horological history. The tattered label identifies it as a clock made by the Sessions Clock Co. This Connecticut company was formerly the E.N. Welch Manufacturing Co., which lost so many assets during a series of factory fires that they eventually had to sell to a smaller firm and was renamed “Sessions” after the new head, William E. Sessions. Perusing the history of various clockmakers it seems that fire was a major “selection event” driving their evolution, worldwide. Apparently, Frédéric Japy’s successful legacy of co-localizing all operations to enhance productivity/affordability also made clockmakers more susceptible to sudden catastrophe.

Back to our story, this early Sessions clock has a black enameled wooden case that possesses fine engravings and an exquisitely ornate dial housed within a brass (or brass-like), flat glass bezel. As with similar clocks from that era, the case is loaded with other metallic gimcrackery. Some of this was meant to imitate bronze features gracing their French counterparts, but the rest appear to be an American fling with rococco-ism that probably merits further research to determine exactly what they were attempting to accomplish. Still, it is a stately looking object on my shelf with a dear familial connection and, unfortunately, a sprung mainspring.

My Sessions black mantle clock, c. 1905

Remnants of the original label

Since the label still references the E.N. Welch heritage, I date the clock to near the corporate sale of 1903. A cursory Google search, once again, turned up its marble doppelgänger of a slightly earlier period.

Japy clock c. 1880

(reproduced from harpgallery.com website)

So that is the story of three black mantle clocks of common pedigree. Variously produced some 120-150 years ago in France, New York and Connecticut, and after some traveling about they now all reside in my Massachusetts home. That’s quite a testament to influence if you think about it. The design of this French clock was so powerful that it was copied across the globe, spawning a multitude of facsimiles wrought from local materials and produced by the millions to be traded even more widely, yet all striving to be the black marble clock. Individually, these clocks are now treasured as heirlooms. Much like a beloved family recipe, they were selected to satisfy a long ago taste, enjoyed in their time, transported across international and state boundaries, and handed down for succeeding generations to partake. Bon appétit!