Under the Red Top

making the best of life & woodBack to Nature

A good friend of mine, David, has a sweet Winnebago/Mercedes camper van and an ambition. His camper van, Isabella, he uses to explore the wonderful New England forests, his ambition is to convert the drab doors and drawers of that camper into beautiful wood. Now, I gather that upgrading features on these campers is a popular pursuit; and why not? It gives you the chance to customize your living space on a scale that is more approachable than a whole house. In a larger sense, replacing factory components with high end gear has long been a passion of the maven class, but the ambition here was different … better. It was about getting back to Nature.

Isabella in the wild

Design

This would not be the first upgrade. During an earlier makeover, the owner had covered the original gray linoleum-like door and drawer surfaces with cork, and had also swapped-out the plastic latches for those bold, stainless steel clasps used in boat cabins. This took the vibe in a more earthy direction and also created an appetite for natural materials. As a next step, it was thought that replacing the cork for actual wood would add interest and also brighten the space. The scope was 4 drawer fronts, 3 cupboard doors and a large, bi-folding lavatory door.

In discussing the Project we agreed that it should be an easy endeavor, especially if we were to reproduce the dimensions and edge profiles of the parts being replaced. The plan was to create solid wood drawer fronts and doors. Today, these parts are typically made from manufactured wood products (e.g., plywood) for reasons of structural integrity, but we hoped to get away with using the untamed material so as to capture the best of Nature. For the large, bi-fold lavatory door the strategy was to create a 1/4 in. thick wooden veneer which could be applied, just as the cork was, onto the existing door’s surface. It would be too much to ask a solid plank door of that dimension to stay true, and this way we could most easily utilize the locks, vents and piano hinge of the plywood original.

Image from within the camper showing some of the cork clad doors/drawers.

Materials

Our goal was to select a light-colored American wood, loaded with character and easy to finish. Oak was the quarry as we entered Highland Hardwoods, that cornucopia of quality lumber. And their flat sawn oaks were indeed “nice”, but also a bit sedate. With only small door and drawer surfaces to work with we were looking for plenty of wood grain action. The hard maple and hickory were “interesting” but, with their reputation for being tough to work, we took a pass. Likewise with the rustic white oak, “lovely” but too much of a twist risk for this application. Unexpectedly, we happened upon a fetching pile of yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis). These flat sawn, curly planks had it “all”, with sharp contrasts of heart and sap woods, and a grain feature that popped like terrain on a topo map. Sold! It’s nice to exit the lumber yard with confidence.

Curly Yellow Birch

Dimensioning

The methods for constructing the smaller doors and drawer fronts were essentially identical. During this process, the existing components would be used as templates before being discarded. This approach not only provided correct positions for the new hinge/drawer attachment screws and latch openings, it also made shaping the exact edge contours a snap. Here’s how it went.

Prepare a board by thickness planing stock to 3/4 in. and cutting to rough dimensions. For the larger pieces, two or three such boards were glued together with the aid of biscuits.

Drill holes all the way through the original drawer front/door parts at all attachment screw points.

Using screws, attach the original door/drawer front to the back of the prepared board employing the same attachment holes utilized by the drawer fronts, and adding a couple screws, as required, for the doors.

Trace the outline of the template in pencil and drill all hinge screw holes into the doors using the guides prepared in step 2., then unscrew the template from the piece.

Cut out the shape at the bandsaw, staying just wide of the pencil line.

Cutting out a rough drawer front at the bandsaw (note the attachment screw holes)

5. Reattach the template with screws and then cleanly shape the perimeter at the router table with a flush trim bit using the template as a guide.

Trimming the wood edge flush with the template

7. Drill-out the latch hole using a 2 inch Forstner bit at the drill press, and then unscrew the template.

Drilling the latch hole using the template for positioning

8. Repeat these steps for all seven of the drawer fronts and doors.

Dimensioning complete for the 4 drawer fronts

Even with those glue-ups for the wider pieces it all went rather quickly. We encountered a couple incidents of tear-out at the router, which might be expected from this curly grained wood, but these could be adequately repaired and the overall results looked great.

Small doors completed

On to the lavatory door. To make the veneer pieces we would need to re-saw a couple of long planks in two, producing 4 boards that could be thickness planed to 1/4 in. and then mated back together along their edges. Even with a good bandsaw, slicing a 6 foot long, 8 inch wide hardwood plank down the spine can be a challenge. David stopped by to assist with these cuts and then remained to play catch on the thickness planer. All went well.

Resawing a birch plank

Slimming-down the veneer boards

Now for the aesthetic part. There are a few choices to be made when pairing up four panels on a door like this.

1. To book match or not? Certain grain patterns lend themselves to the kaleidoscopic thrill of book matching; that is, orienting a pair of boards opposite each other like pages in an open book. While the mirror effect can be dramatic, there’s a price to be paid in chatoyance, a grain-dependent optical phenomenon which, in book matching, typically makes one panel appear darker than its mate. We favored the extra drama. When book matching there’s also a decision for which edge to use as the mirror plane. I’ve always found that the grain gives you the answer here, as one permutation generally transcends the other, which was again the case.

2. What’s the sequence? Since the resawn veneers come in pairs (e.g., AA, BB), and this door has four panels, side by side, there are two different book match sequences to consider: AABB or ABBA. Taking the central piano hinge of the door into account we opted for the “big picture” book match of AB|BA. The central pair (BB in this case) was selected as the one with the best pattern to reflect.

3. Up vs. Down? After settling on the eye catching stuff this final decision is more a matter of propriety. There are two possible board orientations, related by 180°, and you want to select the one that will not make the grain appear upside-down. A furniture design maxim is to have the grain “heavier” at the bottom, soothing our natural sense of upward growth. (Look around your house and you will notice this on chests of drawers, door panels, etc.) To do otherwise would sire a freak of Nature. There is a lot to think about when building responsibly!

The final pattern, all things considered

To complete the door, each AB pair was glued together and then the seams leveled smooth with a card scraper. These constructs were prepared 1/8 in. longer and wider than a half panel of the existing door, the excess material to be trimmed following assembly.

Glueing together an AB veneer panel

Assembly & Finish

Assembly of the bi-fold door involved adhering an AB panel to each individual door section, one at a time. We used a version of LIQUID NAILS® for this (LN-2000) dispensed from a caulk gun and, again, David was on-hand for this operation. Taking turns, he would dole out a couple beads of adhesive onto the linoleum door which I then frosted smooth using a notched trowel. With the wooden panel laid “goodside-down” on the shop floor, a disassembled door section, laden with a full tube’s worth of adhesive, was brought over top and carefully laid in place. Boxes of books were employed as extra weight until the adhesive dried and it all went well.

Applying LIQUID NAILS® to a door section.

Door panels being bonded to their veneer under a couple hundred pounds of books

Once the veneer was attached, the remaining tasks were to trim the edges and then re-create the original openings for mounting hardware and vents. I removed the extra veneer about the edges using a hand held router and care. Given the propensity for tear-out with this wood I needed to go slow while maintaining the router perfectly upright. To assist with the second requirement, I fashioned a wooden “outrigger” to mount the router on. Keeping that outrigger board flat to the door surface as the router was slid along the edge was easy and ensured a true cut.

Trimming the edges with a flush trim bit and outrigger

The various openings were then re-created using a combination of hand drill, sabre saw and chisels completing the woodworking part of the Project.

Book matched door panels

The drawer fronts, doors and veneered door panels were taken back by David for final finishing, and he did a terrific job. To begin, all parts were sanded to #220 grit and then the sharp edges broken for a smooth touch. To get the most from the curly grain, the outer surfaces were further sanded step-wise, #320 then #400, producing a super smooth polish to the wood. Following this, two light coats of gel polyurethane were applied. This brought out the colors nicely, making the wood seem alive. Lastly, to get that perfect “feel” a coat of wax was rubbed-in and buffed.

Final assembly was a matter of (David) re-installing the stainless steel clasps and other hardware before mounting the parts back to their original positions within the camper. While difficult to capture in pictures, the finished doors/drawers add a cozy warmth to Isabella’s interior. Feels Natural.

"I like to section hike the Appalachian Trail and the Long Trail and I frequently refer to topographical maps in my adventures. When I saw the wood we chose in the lumber yard, the grain immediately reminded me of the maps. I love that the finished project allows me to think of hiking whenever I see the wood grain inside."

David

Room with a View

First of all, I did not write this blog post, nor did I create the table it describes. These are the work of my good friend, Brian Jones. Here’s the backstory.

A while back, Brian inquired whether I had any plans for a work table that he could execute with the collection of hand tools he uses for home repairs. The answer was essentially: “Probably. But wouldn’t you rather have a nice table, instead?” He took my curt response in the manner intended, and after some further discussion he also took me up on an offer to come build his table using my tools. In taking on this Project it was implied that he would be responsible for the blog post, as well - both turned out great.

Room with a View

by Brian Jones

Adjoining our pre-Revolutionary home in Dover MA, is an old New England carriage house. On the second floor, slide-windows overlook conservation land that is the roam of deer and coyotes, together with bluebirds and (it is said, though I’m yet to confirm) bobolinks. I want to perch up there, pondering the view and charting my own roamings, like a tricorned explorer in the captain’s cabin of an old Galleon, pondering the horizon. However, the bottom of the windows are 53 inches above the floor-boards.

And so, the desire for a high-stool ‘map table.’ One that reflected the solidity of the beamed space and of the intentions that would be conceived on its surface. Surprisingly an aged example of something along these lines proved difficult to find and so I asked the advice of an old friend, Mark Goulet, who now hones his craft in the woodworking heaven that is the Red Top Workshop. Mark proposed that he guide me through the process of building such a table; an offer as generous as it was welcome, given my complete lack of woodworking knowledge. What would be better than communing through a New England winter, while working on this project? The neighborly enterprise seemed itself in keeping, with the lineage and life of the old carriage house.

Given Mark’s passion for the Arts & Craft style and ethos, he quickly suggested we re-dimension a Gustav Stickley dining table design for this purpose, which seemed perfectly in keeping with the aim. The plan then was for me (and initially, my son Neil) to spend several days through the winter, over at the Red Top Workshop, being initiated into the wonders of woodcraft and testing Mark’s reserve of patience and forbearance.

Table No. 622, Gustav Stickley

From: Bavaro, J.J. and Mossman, T.L. The Furniture of Gustav Stickley (1982).

We liked the simplicity and heft of ash and last October travelled to a New Hampshire yard to select the lumber. With a few tweaks of the plan to accommodate dimensions of the available timber, we were ready to kick off.

Our first introduction was to the jointer, thickness planer and band saw, to prepare the pieces that would be combined to form the square legs (below). Mark explained to us some basic elements of doing things right, like reading the grain in order to feed the wood in the optimal direction to minimize tear out, and careful entry/exit from the planer to minimize sniping. This very first step, converting raw lumber into clean, true-squared sections, is a magical transformation for the novice to witness. To look at a stack of raw lumber and be able to visualize how the elements of your construction will emerge is truly a skill born of experience.

With that done, we needed to create a mortise in each leg, to accommodate the bottom rails. This meant an introduction to dado blades on the table saw to carve out each half of the mortise (Gustav took a harder route to creating this joint). The table saw is an unsubtle implement, but effective. Mark’s methodical and unhurried approach seemed ever more important around this ferocious tool. After re-jointing the half-legs, the next new tool was the biscuit joiner, which set us up to glue and clamp, to provide the first look at the solidity of the whole leg (below).

Our next task was to create two rails that would tenon into the mortise in each leg. After again preparing and dimensioning the lumber, we used the dado blade to do most of the work hewing out wood to craft the tenon, which we then finished with chisels and hand planes, iterating against specified leg mortises to create a sharp, tight fit (below).

Having achieved this to our satisfaction, we turned to making the two chunky “cleats” that would support the table-top and be mortised to accept a square tenon at the top of each leg. This comprised, for each case, preparing, dimensioning and gluing two sections of wood, to form the basis of a deep, solid cleat. With that complete, we set to creating the square mortise and tenon between the top of each leg and the respective cleat. This involved careful labor with the band saw to create the tenons, and the experience of a new device in the mortiser to create, well, the mortises. The resistance of ash was experienced directly during the mortising, with the act requiring a bit of muscle on the lever of the mortiser and generating significant heat in the wood and bit, with ejected shavings showering hot on the hands. Of course, all four tenons and mortises were each whittled to their matched finishes by hand chisel, ensuring a tight clean fit (below). The last act for the cleats was to run an angled cut with the miter saw, to shape a long and elegant bevel at each end.

Paring the stop mortises on the underside of the cleats

Next, we returned to the H-stretcher. Creating the longitudinal stretcher required forming a long, broad tenon on each end of the prepared plank. This we did with the combined application of the dado blade and band saw (below).

Each rail needed itself to be mortised to accept the longitudinal stretcher. Our initial plan was to use the mortiser to do this. In principle this was a fine plan but driving the mortiser bit through such a depth of dense ash proved a step too far. The heat generated began to char wood before the full depth could be achieved. So, we reverted to Plan B, drilling a series of holes with a Forstner bit on the drill press and completing the task with hand chisels. Again, we carefully fitted the designated mortise/tenons by hand chisel and sanding. The dry fit of the frame was looking good (below).

We then turned to the table-top. We started with a first pass jointing and planing of the five planks, cut at excess to required length. One of the advantages of hand-crafting is the ability to make precise choices along the way about what shade and grain you want where, what ‘imperfections’ add character and which should be hidden. The raking afternoon light in the workshop provided an unforgiving magnifying glass for that process. That came to the fore with the table-top and we carefully designed the pairing and placement of the boards we wanted in the final surface. Having debated and concluded, we set to work carefully and iteratively jointing and planing the paired edges, to create seamless contact along the entire length. Achieving this is one of those tests of craft and commitment to quality, in which Mark set the standard. Having done that, we pulled out the biscuit joiner again to put three biscuits in each seam. We first glued and clamped the outer two pairs of planks and left them to cure. At the next session, with the help of Joung (Mark’s wife) to move and stabilize the unwieldy jenga, we glued and clamped the three segments in one go, to create the full five plank width. This required Mark’s longest pipe clamps and unbolting and moving his workbench to make space.

Closing in on the finish there were a few tasks left. With a combination of patience+hand plane and dowel plate+grunt, we fashioned eight short 5/8” dia. dowels to pin the rails to the legs. Grunt was also needed to drill out long holes through the legs to accept the dowels, but achieving a pretty nice fit in the end. A finishing cut on the ends of the stretcher took that back to final length. We also created mortises and tusks here that would firmly stitch the whole thing together. Then the project’s final cut, using the track saw to make two smooth long cuts across the width of the table-top, to take the ends back to length. During one of these cuts a slight obstruction delayed the sweep of the saw and caused a little saw burn on the edge. Being a craftsman, this gnawed at Mark overnight, so he did a final dust cut pass on that edge the following morning.

And before we knew it, we were just left with finishing; breaking edges, scraping, rounds of sanding and finally two coats of Arm-R-Seal wiping varnish. Even this straightforward process contained two revelations for the novice. Firstly, the near miraculous use of an electric iron and damp cloth to remove minor dents where the wood fibers were yet intact. Pure magic. And secondly the lovely simplicity and effectiveness of a cabinet scraper, to make the first pass smoothing. Seeing the final grain blossom on application of the varnish pulled back the curtain on the art of ash.

Carriage House Table (39”H x 60”L x 36”W)

We countersunk a series of table-top fasteners and carefully squared up and marked screw positions in the shop. It was then time to transport the table parts and assemble in situ, which went without a hitch. And so, this ‘map table’ now sits among aged oak beams, commanding a bucolic view, ready to inspire the roaming mind.

What a privilege and a pleasure to spend time through the winter, learning, creating and talking with Mark under the Red Top. Patient and deliberate working of wood, to the quiet accompaniment of Blues music, the smell of the wood stove and the shifting light slanting across the fields. A pleasure too, to share hand-crafted lunches with Joung and Mark, along the way, talking about everything from bats to life in Korea. Communing through wood. Surely something familiar to the pre-Revolutionary residents of this old house.

Seeds

Found along a garden wall in the Cotswolds

My annual reflection and some thoughts on the year ahead follow.

Productivity at the workshop in 2023 was on par with prior years but with much more variety. In sum, ten Projects were completed, and these included a couple restorations, a T-shirt and a yet to be revealed clock. Non-furniture Projects like those restorations remind me of the days before the Red Top when home repairs and sprucing up antique store finds were my thing. Now with a shop full of machines, I had gotten away from these rewarding jobs where a tool box, some glue and a can of varnish were all that was needed. Working to make clocks and furniture provides a nice constructive outlet, but refinishing a worn chair remains a worthy endeavor. Both seek that thrill of completing something special.

Of the past year’s builds I have to say that the No. 220 Prairie Settle was my finest. When I began that Project in September of 2022, I worried that it was perhaps beyond my abilities. That one piece took half a year to complete but it turned out well and gives me joy whenever I look or sit upon it. Completing No. 220 also gave me confidence to continue challenging myself in the workshop and at the design desk. A new clock design and a mirror, followed by loving renditions of a marble clock and two East Asian classics provided additional opportunities to stretch. As we begin 2024, fresh lumber for three new Projects is conditioning in the shop.

Tackling new builds is a great way to learn but in 2023 I also hit the books to school myself on the history of clocks and, even more so, Arts and Crafts furniture. Historically a social movement rather than a design style, the ideas that shaped the Arts and Crafts period (1880-1920) continue to edify us as we experience a rising demand for maker spaces and a renewed desire for hand made items. I wrote about one aspect of this movement in win back art and feel very strongly that we must look for and appreciate the creativity in all we do. It is important for our well being, and I now wear that ethos on my back.

The Projects and those additional studies were instructive, but the biggest influence for me in 2023 was the experience of seeing English Arts and Crafts furniture in the museums and shops of their native land. Book illustrations can excite, but an encounter ignites. My memories of those encounters are vivid. Their accumulation has formed new ideas that, like seeds, I expect will germinate as conditions favor.

Happy New Year all!

The Bento Board

Here’s the story: We wanted to create a Holiday gift for some dear friends. It needed to be small and, since this idea only occurred to us a couple weeks ago, it also needed to be easily made. Recalling their fondness for Japanese culture and looking over a few scrap boards from past Projects I had the idea to build a charcuterie board in the form of a bento box. And here’s how it turned out.

Design

No doubt we have all enjoyed a bento box lunch, made up of small entrees tucked neatly into their own compartments. The Japanese term bento is thought to come from biàndāng, a Chinese word which means “convenience”, and it describes a single portion take-out lunch. In Japan the container for this lunch, also called a bento or bento box, has been around since at least the sixteenth century. This box is a clever invention that utilizes partitions to keep the individual flavors pure and, over the years, design evolution has brought forth dozens of box configurations. What I was looking for was a traditional form that would evoke a bento, even if no compartments were present. If gotten right, this would be a flat serving board that felt like a bento. Searching online I found a picture of a lacquered bento box from The Japan Times that both looked the part and could be replicated with ease.

Bento box exemplar

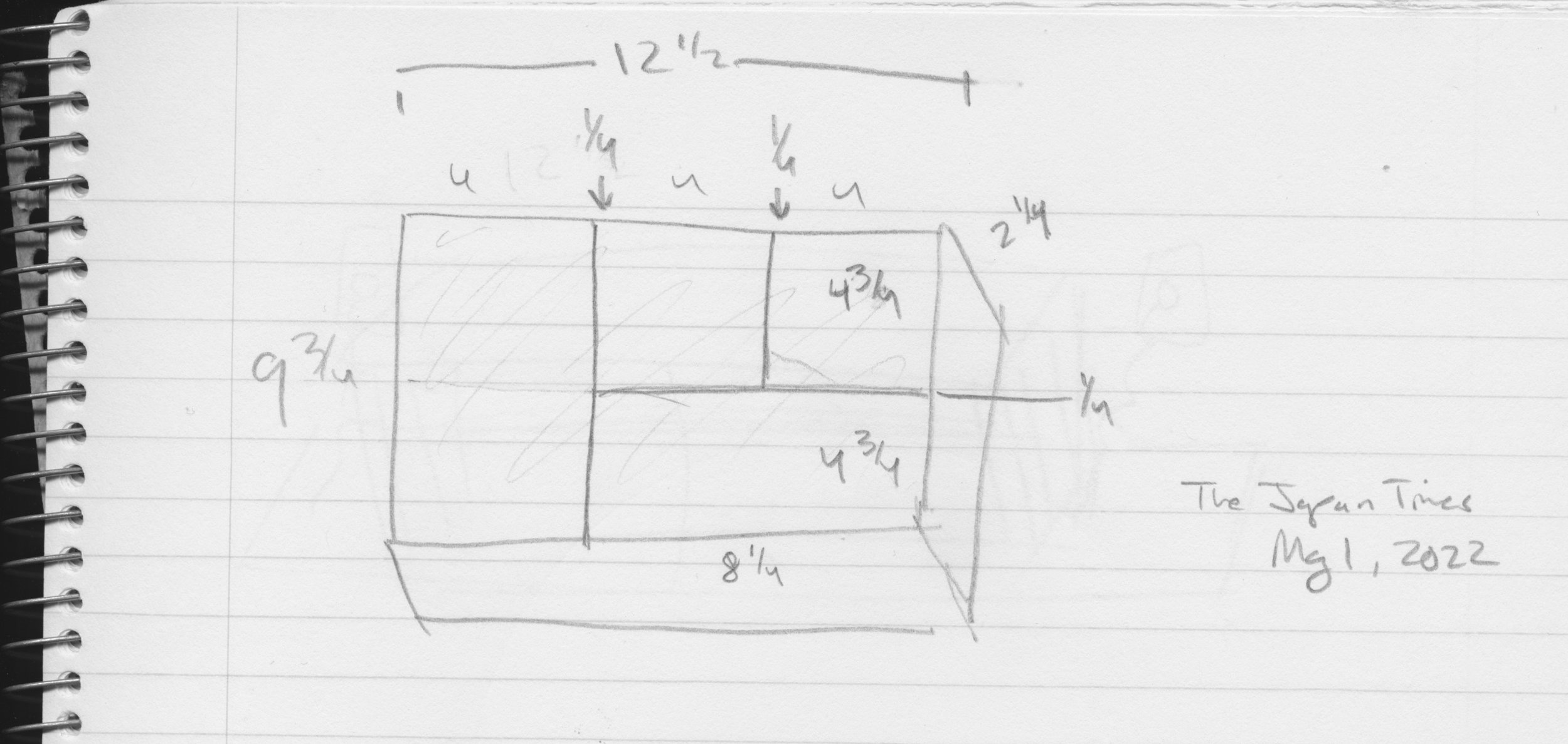

As far as plans go, a simple reference sketch with dimensions was all that was required.

Make this.

Materials

As it turns out, the intended recipients had earlier gifted me a couple of antique spruce boards leftover from their recent home expansion project. These centuries-old beauties were reclaimed from a Boston factory building during demolition and then repurposed for the construction of cabinetry during their renovation. Anyway, the wood was full of character, cracks and nail holes, and a small chunk off the end of one board would serve nicely here. Some leftover black walnut would be used for the sides and inlay, and I would put some cutting board feet on the underside.

Spruce and walnut stock

Dimensioning

The wood was first cut to rough lengths and then prepped at the jointer, yadda, yadda … No time for a blow-by-blow account, but you can follow the narrative with these pictures.

After the spruce was planed to the proper thickness, it was grooved at the router table and then the surface cracks (age defects) were filled using epoxy.

Due to their perpendicular orientation, the inlay strips were glued in one at a time and then hand planed flush to the surface. (Note square cut nails holes on the edge.)

With the “partitions” in place the walnut sides were cut to final lengths on a 45° bevel at the table saw

Glueing up the sides

Because the two short sides were glued to the spruce’s end grain I wanted to add some additional fasteners. Walnut dowels did the trick. (Note cutting board feet attached to the underside.)

After a final sanding, mineral oil was applied to the surfaces followed by two coats of a hard natural wax.

A final buff and a ribbon finishes the Bento Board.

The Alarm Clock

I have always appreciated alarm clocks. In addition to keeping time, these fellows let you, the user, enhance function by programming their works. This sets up a charming, human machine symbiosis which is the reason why we buy them instead of the less functional alternative. The current Project is an alarm clock restoration, of sorts.

It seems that among the family artifacts & heirlooms my brother, Mike, happened to acquire the guts of an old, 1940’s electric alarm clock that once belonged to our great uncle Louis. As with many family keepsakes he doesn’t remember how he assumed ownership, and I only became aware recently when he presented me with the naked works and a request to build a new case for them. The clock would have been originally clad in Bakelite, that early plastic which we presume was somehow damaged beyond repair, however, the clock face was unblemished, and it appeared to keep good time. This motorized timepiece would have been purchased shortly after electricity arrived to our area of rural Michigan and so I imagine that it was an extra special item in its day. Here’s a picture from the internet showing its original form.

General Electric clock model 7H154

Design

The art deco styling of the original evokes an era of home cooked meals and evenings by the radio. We wanted to preserve that feel, but an exact reproduction, replacing plastic for wood, was not the answer. First, the stocky 4 x 4 inch bedside form would look out of place on a shelf in my brother’s study and, more importantly, I was not sure I could execute the curved case top with success. The solution was to keep the curve element as part of longer, more pronounced “pillars” framing a rectangular chamber that would house the clock mechanism. While still a square 7 x 7 in. on the face dimension, it was anticipated that the illusion of verticality provided by the dominating pillars and the offset dial mount would give a more appropriate look. The motor on this clock generates heat and so the plan was to forego the box bottom and also leave a gap between the sides and top to promote cooling by convection.

Rough plan with front view showing two possible variants of the curved pillar

Materials

The mechanical part of this build was in hand except for two missing bolts used to mount the works to the case. Replacements for these were obtained at the local hardware store. For wood we chose quarter sawn white oak, that mainstay of solidly built furniture from this period. And in the spirit of Reclaim•Reuse•Recycle, a few leftover scrap boards from past Projects would be used.

White oak boards

Dimensioning

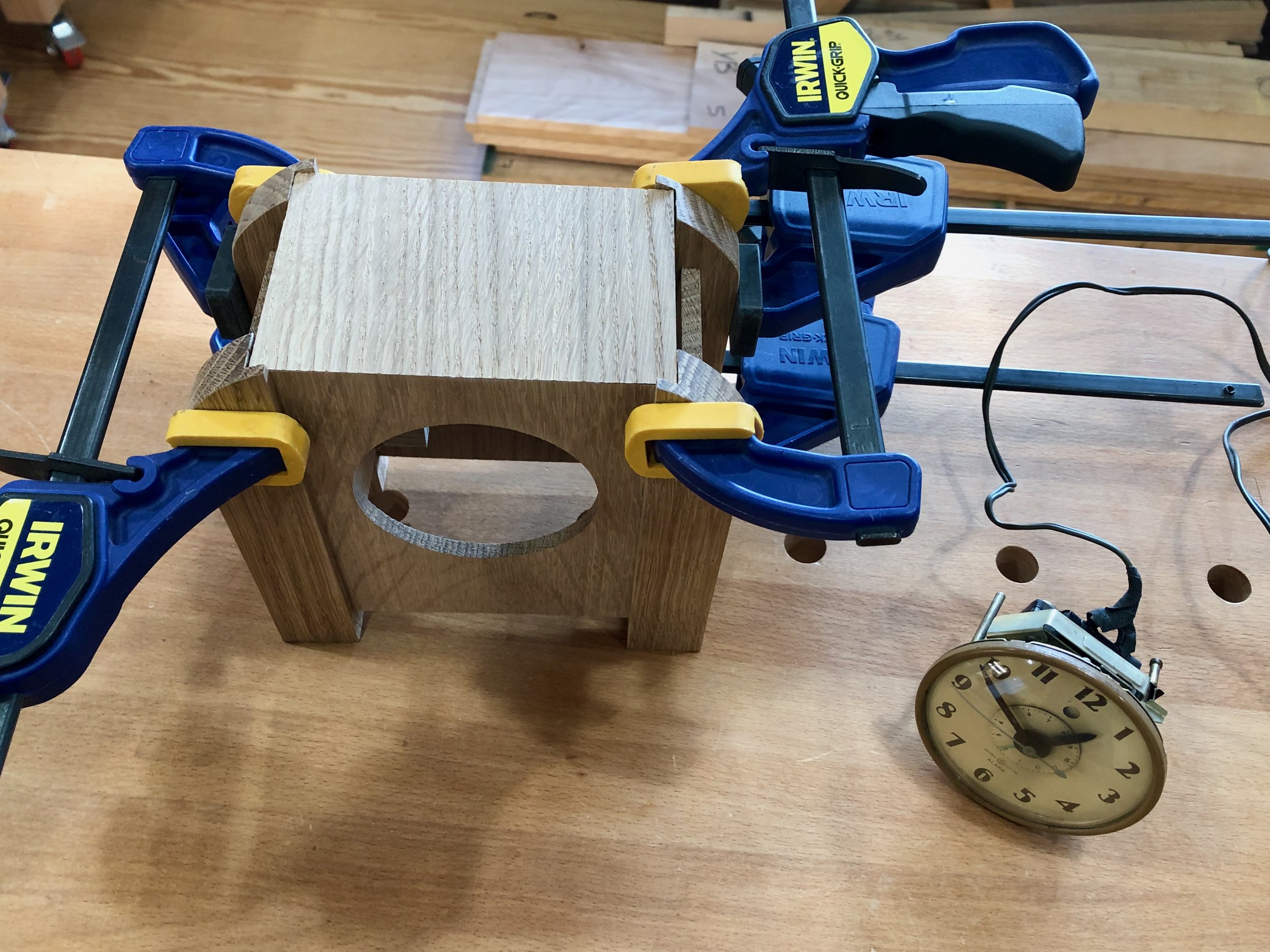

The parts for the case were easy to make. I needed four pillars (1 1/4 x 3/4 x 7 in., W,D,H) and some flat panels, thickness planed to 1/4 in. in depth. Some grooving in the pillars would hold the panels, and the seams along the top would be mitered. Just as with the plastic case, this construct would expose no joinery. Although “easy to make”, it required the use of all nine of the heavy power tools in my shop to do so. This included the smaller bandsaw, which was used to cut both the circular opening in the face as well as the curved pillar ends. Can’t have more fun than that!

Cutting semi-circles out of the half faces using a homemade bandsaw jig

Hand planes, rasps and sandpaper were used in the bench room to further refine the pillars and to establish a tight fit of the panels in their dadoed slots.

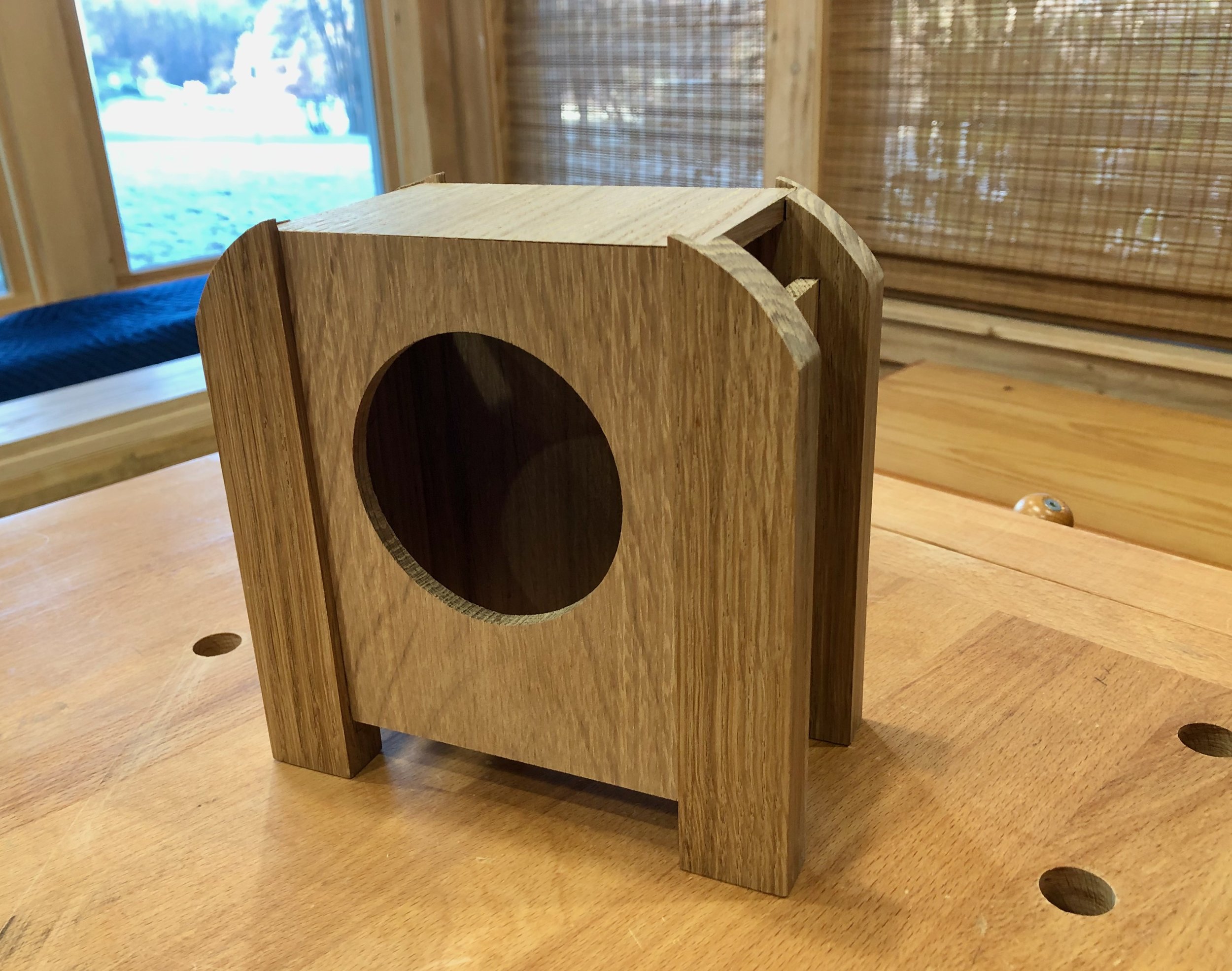

Test-fitting the front and back panels

It all came together rapidly up to this point. The next step was to create a top to be joined with the front and back panels. The plan was to use mitered joints for this, which meant cross-cutting these pieces to their exact lengths on a 45° angle at the table saw. I cut the top first from a longer board in order to practice getting it right. Next, the front and back were cut to identical lengths. To get the whole thing fit together I also needed to chisel out a small section of the pillars. After marking the cuts with a knife I used a pull saw to make incisions where possible. I then placed a supporting plywood scrap into the groove and chiseled-out the remaining waste. It all went well.

Removing the top corners with a chisel

With the top settled into place I could make a final measurement for the width of the sides. Two side boards were then cut to size and the entire case snapped together nicely in a dry fit.

Dry-fit case

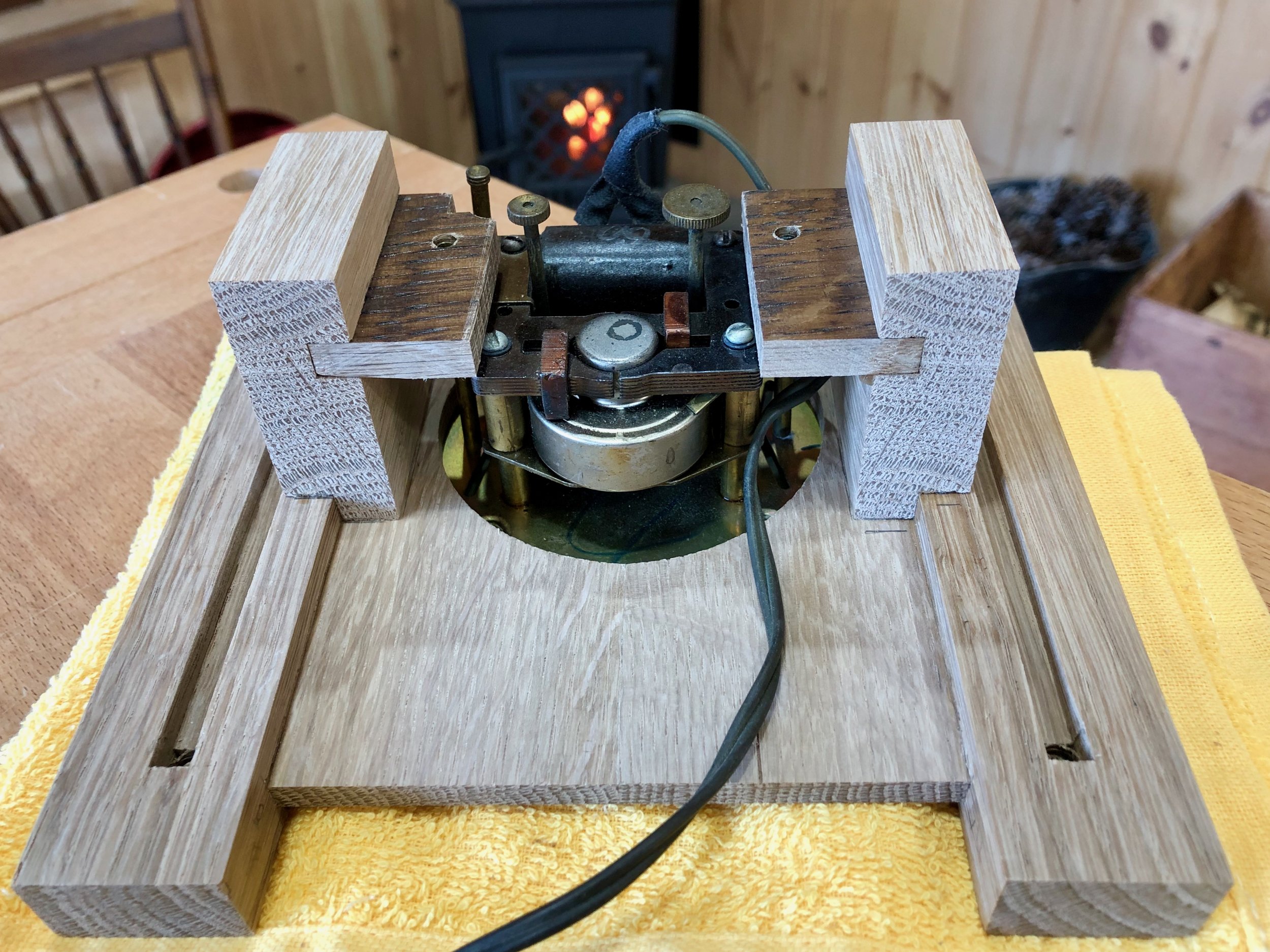

Only two operations remained prior to final assembly, both of which I had yet to engineer: mounting the clock works to the case; and creating a back door. The original clock used two bolts to mount the works to the backside of the case, and that backside contained three openings from which protruded the knobs and buttons used to set the clock and alarm. During design I had ruled against this solution as it would necessitate making the 7 inch tall clock a narrow 2 1/4 in. in depth and I was going for a different look. This look would necessitate a doored opening to access the control knobs. I could still use two long bolts to reach the back of the clock, as designed, but they would need to mount so close to the door opening that it was not considered a robust solution. The chosen method was to mount the mechanism to the front of the case by way of a couple wooden blocks glued to the interior, through which the bolts could be tightened.

Clock works mounted to the front board

Finally, on to the access door. The back panel, having already been cut to size and fitted, was now a high-value component so getting the door right on the first attempt was important. It was decided to cut out an opening in this part and then source the door from another piece of oak, rather than use the waste material for this. However, with no other framing, that door would need to fit as if it were a cut-out and so the plan was to establish the opening and then trace this pattern onto another board to define the exact door shape. A Forstner bit at the drill press was used to bore holes in the back board along the perimeter, followed by a chisel to define the straight edges of the opening.

Chiseling out the door edge

Next, a door was cut out of a prepped white oak board and then the edges were hand planed and sanded to achieve a uniform interior fit.

Assembly and Finish

Glue-up of the remaining parts was straightforward. Once dried, the miter seam was treated with a burnisher to close-up the hairline gap, and all clamp marks were removed with sandpaper.

Assembling the case

To preserve the wood I used Jeff Jewitt’s rendition of L. & J.G. Stickley’s so-called “Aurora” finish: medium brown dye, antique walnut glaze, satin varnish. I think it gives the oak a nice warm feel and still lets the medullary rays shine. After buffing the finish, the clock’s works were installed and tested. Finally, a couple of brass butt hinges and a round brass knob were applied to complete the access door.

Back door

Mike’s alarm clock now has a new presence; bold but friendly, and with a hint of nostalgia for simpler times.

Metamorphosis clock

Korean Stand

Korean furniture has but a few characteristic forms and these have served their storage, writing and dining needs for millennia. Distinct from other East Asian designs, Korean pieces tend to be stouter, less decorative, and more “earthy” than the island or mainland counterparts from Japan and China. And in my view, no form is more unique to that peninsular nation than the book storage and display stand, the so-called sabang t’akja. These stands, about 16 inches wide and no more than 6 feet tall, have several layers of shelves and can exist free of cabinetry, but often they will be anchored by a doored compartment for stacking books. The more utilitarian versions include small drawers, as well.

Korean book storage and display stand archetype (sabang t’akja)

reproduced from: Wright, E.R., Pai, M.S. Traditional Korean Furniture, Kodansha: Tokyo, 2000.

For lovers of East Asian design, sabang t’akja are downright charming. I think it is the combination of a sturdy base supporting the thin, beautifully proportioned shelf framework that gives this iconic furniture its appeal. Of course, the wooden material, joints and hardware all do their part, too. One of my earliest Projects in the workshop was to excise the shelving and just build that bottom compartment; this time I’m making the shelves.

My motive for this Project was to make a display stand so that we could unpack and put out some of our “precious” pottery, and for a moment I seriously considered using all authentic joinery in the process. Sabang t’akja are generally constructed using the so-called “swallow beak” joint. Traditional Korean furniture relied heavily on this method, adapted from the construction trade, for fastening parts. Structurally, it is a modified mortise and tenon joint that creates a solid corner. The “beak” portion serves as a second registry element that, along with the internal tenon, securely mates a pole and a rail, in olden days, without the need for glue or fasteners. It also serves to convert a simple seam into an interesting design element. If you’ve never noticed these on Asian furniture before, you will now.

Example swallow beak joint (not mine)

Alas, that consideration did not last long. I taught myself the rudiments of this joint from a book on Korean furniture making, and my practice joints were “okay” but not good enough for living room furniture. More practice would undoubtedly improve things but I found no joy for me there and I began to dread the thought of sawing/chiseling dozens of these joints to finish the Project. I also happened upon a few pictures of sabang t’akja made with traditional mortise and tenon joinery and that sold me on the path to take here. I’ll master the swallow beak joint one day on a smaller piece.

Design

The display stand, itself, will be a replica of another example found in the book, Traditional Korean Furniture, referenced above. Dating from the mid-nineteenth century and now part of the National Museum of Korea collection, this example stands 59 inches tall and has no cabinet. It is symmetrical, delicate and beautiful to my eye. The dimensions of the poles and shelves were calculated from the photo, below. Replacing the original swallow beak joints (n = 40) with mortise and tenons is simply an elimination of the beak work.

Korean display stand exemplar

Materials

The original display stand was crafted using pine wood for the frame and paulownia for the shelving. These softwoods were employed extensively in traditional Korean furniture making, but I wanted to use hardwood for my version and so I decided to use red oak (Quercus rubra), quarter sawn at the lumber yard.

Red oak stock

Dimensioning

There are only five part “types” in this piece, and that simplicity of structure accounts for its beauty. They are by my nomenclature:

poles (4)

top rails (4)

rails (16)

shelves (5)

tatami-zuri boards (2)

The poles and rails come first and, with these, there is a specific sequence required for joint creation: mortises before tenons; grooves before shelves. To begin, the oak was prepped at the jointer and thickness planer, and then the poles, top rails and rails cut at the table saw to their final width dimensions (1 in.) but left long. The depth of these parts were set last: the poles and top rails at the thickness planer (1 in.); whereas, the rails were first resawn at the bandsaw and then thickness planed to 1/2 in. To eventually accommodate the shelf boards, a 1/4 in. wide x 5/16 in. deep groove was made in the rail parts using a dado blade at the table saw. All edges were then smoothed a bit with a card scraper to remove mill marks. Things will get finish sanded near the end of Project.

Poles and rails cut to their working dimensions

The joinery starts with the poles and before any of that work is done they first need to be cut to final length and marked. To define the height dimension, I measured down 60 inches from the top of each pole and sliced a 1/4 in. deep groove here on all four sides using the sliding miter saw. The grooves define a 1/2 in. square “core” which will be converted into a tenon to hold the tatami-zuri boards later in the build, but for now I will leave a stub the same dimension as the pole to make the next few operations easier. The poles were then chopped 3/4 inches beyond the groove to give parts of uniform length.

The poles were labelled for their position (e.g., left/front, etc) and then the position of the top mortises were pencil-marked using a ruler and square. These were cut at the mortiser and, since the top rails are thicker than the “inner” rails, they merited a thicker, 3/8 x 1/4 x 1/2 in. mortise, too.

Next, I needed to somehow cut the 32 remaining mortises, all 1/4 x 1/4 x 5/16 in., at regular positions along each rail. Instead of properly marking all of these positions and then accurately hitting the marks with the plunging mortiser bit I decided to try using a spacer jig. This little invention consists of a 1 in. wide oak board with a 1/4 x 1/4 in. mortise cut through it. A 1/4 x 1/4 in. square cherry dowel was then tapped through this glued opening and cut to a 3/16 in. protrusion on either side. Finally, cutting this board to length, 13 1/2 inches below the dowel, gave me my working jig.

Shop-made spacer jig alongside poles

In use, the jig was inserted into the topmost mortise on the pole, which was subsequently seated on the mortiser bed such that the end of the jig abuts the mortising bit. Plunging at this position, then reproducibly delivers a mortise at the appropriate position below the prior one. This 3-step operation (insert jig, chop, slide to next position) is repeated until you run out of pole. It worked well.

Spacer jig “in use” at the mortiser

Next, it was time to fashion the top rails. I cut the previously prepped & grooved stock to a length of 14 1/8 in., giving me the desired span plus room for a 7/16 in. tenon on both ends. The tenons were cut in a two-step procedure. First, a finishing blade at the table saw was used to cleanly define the shoulders on all four sides.

Top rail lengths defined

From here, a dado blade and cross-cut sled were used to form the tenon cheeks at the table saw. Coming off the saw they were still a bit too thick, but could be easily chiseled down to size during a fitting operation with the poles.

Top rails tenoned

It was now time to make the tenons on the rest of the rails. The pole mortises were cut to a depth of 5/16 in. and so the tenons on both ends should be just shy of this length. With the same span as the top rails, this meant that the rails would need to measure ~ 13 7/8 inches in total. All 16 rails (plus a couple extras) were chopped to this length at the sliding miter saw. The tenons were formed in a manner similar to that described above and then chiseled for exact fit with their assigned pole. Dry-fitting the structure confirmed that everything was square and correct.

Dry-fit poles and rails

The shelves were next, all five prepared in an identical manner. First, a 7+ inch wide, 5/4 oak board was cut into four, 18 in. long sections and one edge of these made flat at the jointer. Each board was then re-sawn at the band saw into three, ~3/8 in. wide panels, giving twelve in total. The panels were then made uniform to a 1/4 in. depth at the thickness planer, and the ten best were taken on to the next steps.

To complete the shelves, the half-panels were first paired-up and the interior edges of each were made uniformly square at the jointer. The boards were then individually chopped at the sliding miter saw to uniform lengths and ripped at the table saw to uniform widths before the pairs were reunited again, this time with glue (and clamps). Next the surfaces were smoothed with a card scraper and sandpaper, each panel was then cross-cut and ripped to a 13 7/8 in. square using the combination of track saw and table saw, and the corners notched-out at the band saw to accommodate the poles. I applied one coat of the Danish oil finish to the selves at this stage. Now, should any shrinkage of the shelves occur after the final finish, it would not expose bare wood.

Shelves complete

That leaves the tatami-zuri boards. These 1 x 5/8 in. boards run between the front and back legs and serve two purposes: they contribute to structural fitness; and also act to spread the load, saving wear and tear on the tatami, that rush floor coverings found in East Asian homes. For these it made sense to reverse the proper order and complete the pole tenons before cutting their mortises. Excess material below the previously sawn grooves was eliminated with a dado blade at the table saw to yield a 1/2 in. square tenon at the bottom of each pole. After marking their positions, through-mortises of this dimension were then cut from prepped boards. In this operation it is best to leave the tatami-zuri boards longer than the final dimension, as cutting a mortise too close to the ends can result in catastrophic tear-out of the wood. (This is a fact!) Following a dry-fit, these boards were marked and cut to their final length.

After one last rehearsal of the assembly process the rails were hand planed to be smooth with their adjoining poles and then disassembled so that all surfaces could get their final sanding. Glue-up proceeded in a swift and methodical manner. I wanted to get all 31 parts put together with glue in the joints while the piece laid prone on the bench, and then flip the construct upright for a final square-up before applying clamps. This required that the glue remained fluid “enough” during the 20 minute procedure, and then harden after clamping. Employing spousal assistance it went pretty well.

Clamped-up stand

Once dried I lightly sanded the structure to erase all clamp marks. To finish the piece I gave it a thorough rub-down with “natural” color Watco Danish Oil. I like how this product livens the grain of red oak while leaving a soft touch and no sheen. Two coats, applied over two days was all it took to complete this satisfying build.

Korean Display Stand reproduced in oak

And our pottery collection now has room to breathe, again.

On display

Thank you Dad and all Korean War era veterans for your selfless sacrifice on our behalf.

Cotswolds Pilgrimage

“Rural England is too absolutely beautiful to be left out of doors - ought to be under a glass case.”

Mark Twain (1872)

I have to agree with Twain’s sentiments of 151 years ago and, in fact, there’s a lot about England that remains “too absolutely beautiful”. Let me show you.

Lately I have gone deep into Arts & Crafts - the movement and, in particular, the furniture. It started with an appreciation for the American, Gustav Stickley, and his Craftsman ideals. There’s certainly plenty for me to learn (and make) in this area but, interested to know the background for his work, I also sought out examples of earlier, English Arts & Crafts pieces. Hmm, I have to say that first impressions here did not enthuse. In general, I found these pieces to be unappealing and, if taste needs a reason, it seemed they possessed “too many notes”. In fairness, I was consulting art pieces and my naïve eye was hooked on square and functional forms, where wood, itself, was the decoration. Vive la difference! But then I read Nancy R. Hiller’s English Arts & Crafts Furniture and became devoted to the form. Nancy Hiller (1959-2022) was a remarkable artisan and insightful writer who used step-by-step reproductions of three iconic furniture pieces in her book to reveal both the Art and the Craft of turn-of-the-century English furniture. It’s an informative and compelling read.

A wonderfully enlightening book

Attracted by the furniture I subsequently became interested in the movement. That is, how was it that these novel forms became important, if not popular? Who designed/fashioned these objects during that brief, 30 year burst of creativity? And what were they trying to achieve? To be sure, there are larger questions in this world, but those were mine. Of course, the answers are all out there in biographies (my favored genre), and to start me off I found some good ones on John Ruskin and William Morris. I also became aware of other works that were either inaccessible or unaffordable, given their location in British bookshops. That predicament, on top of a simmering curiosity, sealed our next vacation destination. We were headed to England to feel the environment, to see the furniture, and to secure reference works of the Arts & Crafts period.

While there are several geographical areas (so-called “schools”) in Britain associated with Arts & Crafts furniture making from the period of ~1880-1910, a region known as the Cotswolds is, arguably, the most important. This magnificent region of rolling hills and villages has been home to humans for over 6,000 years. In fact, it is the largest designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in Britain, covering 787 sq. miles and a popular tourist spot for non-furniture lovers, as well.

The Cotswolds, located in England between London and Wales

While planning our trip, my wife and I had two primary destinations in mind: The Wilson Art Gallery and Museum in Cheltenham, which houses an important collection of Arts & Crafts furniture; and the villages in and around Chipping Campden, where several major designers of the Cotswold School worked. We were certain to happen upon other meaningful sites, but those were the anchors. Our trip began in London where destinations such as the Victoria and Albert Museum also beckoned. What follows is not a day-by-day journal, but just some captioned pictures, intended to give an appreciation for the area, the furniture (and the clocks). I hope you find them interesting.

The original adjustable “Morris Chair” designed by Phillip Webb. Copied by many, and catapulted to stardom by Gustav Stickley; this is an important early piece. (Victoria & Albert Museum)

Magnificent chair, desk, clock and river rug by C.F.A. Voysey (V&A)

High-backed chair by Charles Rennie Mackintosh of the Glasgow School (V&A)

Frank Lloyd Wright chairs, likely influenced by Mackintosh and other Arts & Crafts designers(V&A)

Sideboard by E.W. Godwin. While striking, it represents a gaudy crescendo to the Aesthetic movement, where ornamentation served no other purpose, that pre-dated Arts & Crafts (V&A)

Korean horse hair gat (hat) and box from the late Joseon dynasty. The lacquered bamboo box is as beautifully crafted as the furniture from this period. (V&A)

Scene through the window at Hill House Antiques, in Kensington which was unexpectedly closed when we visited.

Japanese inspired Tavern Clock from among the many amazing pieces for sale at Howard Walwyn Fine Antique Clocks in Kensington.

The British Museum has an extraordinary collection of important clocks, including this “portable” regulator case clock, taken across the world in the late 1700’s and set up in a field to time an eclipse event.

— intermezzo 1 —

Sharing The Cotswold Way, a scenic 102 mile footpath that skirted our B&B, stretching from Chipping Campden to Bath

A couple interesting chairs found “in the wild” at the Winchcombe Antiques Centre

Left to Right:

Bookcase and desk by C.F.A. Voysey; Chair by (I do not recall); Music cabinet by Benson and Sumner (Wilson Museum and Art Gallery, Cheltenham)

Portion of a coffer by Earnest Gimson. Reportedly, he was in the process of applying the white gesso prior to painting when he passed away. (Wilson)

Settee by Sidney Barnsley (Wilson)

Cabinet with exquisite metalwork by Charles Robert Ashbee. Along with Gimson and the Barnsleys, above, Ashbee was an important Cotswold designer who worked in Chipping Campton, Gloucestershire. (Wilson)

Piano by C.R. Ashbee (Wilson)

— intermezzo 2 —

St. Faith’s Chapel, in the village of Farmcote, Gloucestershire, just down the lane from our B&B.

A volume from the Works of Chaucer designed and printed by William Morris at the Kelmscott Press (Wilson)

Cabinet designed to house the Kelmscott Chaucer works by C.F.A. Voysey (Wilson)

Dresser by Ambrose Heal (Wilson)

— intermezzo 3 —

The eponymous Ebrington Arms, that lovely village’s pub in a building that dates back to 1610 was our home for the final leg of the trip

At the Gordon Russell Design Museum, once part of his furniture manufacturing workshops in the picturesque village of Broadway, Worcestershire.

Dresser No. 229 by Gordon Russell (GRDM)

The Paris Cabinet No. 157 by G. Russell. It was awarded the Gold Medal at the Paris Exposition in 1925.

Chair No. 280 by G. Russell with beautifully executed chamfering, typical of the Cotswold School.

Two Document Chests No. 617 where Russell kept all of his numbered drawings, with Glove Box No. 495 on top (GRDM)

Sideboard and radio case by G. Russell. This sideboard, an icon of mid-century modern furniture, is sometimes called “the double helix” but since it was designed in 1951, two years before Watson & Crick’s DNA structure, I think that is an attribution in retrospect.

I know what you’re thinking, “Please make it stop.”

Scene from the churchyard at Saint Micheal’s and All Angels Church, Guiting Power, Gloucestershire

OK, I will.

I’ll just close by saying that, in addition to the “too absolutely beautiful” sights, this was an inspiring trip for me as a maker. To see the important Arts & Crafts furniture pieces in their own land is to capture them in a way that will last a lifetime. iPhone pictures taken within cramped museum spaces cannot do the job, but they at least serve as reminders. The gorgeous Cotswolds, their charming villages and friendly people surely influenced the furniture designed there, and they also made our trip a smashing success. I even got my reference books!

Lasting inspiration!

A Beloved Board

Here’s a new one; a good one, too. Last week I had a customer bring me her cutting board and asked, essentially, “Can this board be saved?”. It seems she uses, daily, the same hardwood cutting board that had belonged to her mother, and all the years of chopping were beginning to show. One is easily drawn to this board. While not an expensive item, the value bestowed by memory made it priceless. You know the feeling. This project is about restoring that beloved board.

The goal was to make the board “better”, that is, flatter, smoother and less wobbly while keeping the character intact. I started by sizing up the physical attributes and reason for its unsteadiness. Putting a straightedge to the top revealed the primary defect, a 1/4 inch sag over the 12 inch width caused by wear, warp and also failure at the joints. It turns out that this “board” was made up of three smaller boards, which were coming apart at the seams.

Daylight above the sagging board

At this point, all thoughts of cosmetic restoration were abandoned, it now appeared that reconstructive surgery was in order. Sanding/planing, the outer edges deep enough to achieve a level work surface would produce a cutting board with a pronounced belly that still wobbled. The new plan was to remove the legs, slice the board into three at the seams and then plane the top surfaces flat while also removing a layer of worn-out wood. Re-gluing the parts back together and then finish sanding would give a flat, and hopefully attractive work surface for a few more decades of service. I would restore the legs, too, but decided to leave the underside relatively untouched to keep some patina and that sweet Dansk® trademark.

The first job was to cut the legless board into three parts at the band saw.

Dissected board

The three boards then were run, individually, through the thickness planer several times. This revealed their composition to be maple, and also produced hard, useable wood on the surface, again.

With a clean, flat surface in hand, the rough, band sawn edges were then made square at the jointer. Next, the undersides of the boards were skimmed lightly using an orbital sander to clean the surface, and then, to give the new joints a better life, I decided to add some biscuits before glue-up.

Biscuits in their slots

Reassembly using waterproof glue

Once the glue dried, the surface was card scraped to level the joints and then sanded smooth to #220 grit; the edges were treated similarly. Next, I scrubbed the board using a mild detergent and let it dry. This served to raise the grain, which was hand-sanded smooth again. Finally, all of the corners, made sharp by the resurfacing process, were rounded-off.

The legs turned out to be a lost cause. Like fossils within a rocky matrix, the recessed rubber feet had petrified over time and became one with the wood. I found it was too difficult to chisel-out their remains without also damaging the frail wooden legs. And since those feet would need to be replaced anyway, it seemed best to just create four new legs from some scrap maple lying about the shop. This also permitted me to make one of the legs slightly taller than the others to compensate for warp at one of the corners. Stainless steel screws were used to mount the legs and feet which now sat square and firm on the bench.

Standing proud again

A couple treatments with food grade mineral oil, smoothing with a red Scotch-Brite pad in between, completed restoration of the beloved board.

While not the typical Project, this was a very satisfying effort. After witnessing the metamorphosis my wife put in a request for her boards be sanded and reshod, too, so the story has two happy endings. What shape are your boards in?

The T-Shirt

Picking up on a prior post, let me share a new endeavor with you.

After reading my recent analysis of a William Morris quote, you might be thinking: “Wait! If ‘win back art’ is such an important mission, how come I am only learning about it now, some 150 years after it was proposed?” I was thinking the same thing, too; and then it began to gnaw at me. Not that it matters, but I’ve never seen the phrase on a poster or a T-shirt where it might raise awareness, or at least expose itself in places we expect bold ideas to reside. To me that felt like a miss. And so I decided to design that T-shirt - why not?

Design

Now, I have never created a T-shirt before but I have watched my sons make several. In high school they had taught themselves the craft of screen printing and occasionally turned our basement into a “sweat shop of friends” cranking-out fund raising shirts for their school’s bands. I had always admired their stick-to-it-iveness on these projects, as well as their skills, and it continues to inspire me. My plan for the current shirt was to stop after the design phase and project manage the rest of the endeavor using trained professionals.

“Winning back art” in the basement (2010)

Following a discussion with my friend, Bob, and a brief internet search, I learned that there are plenty of companies out there ready to create custom printed shirts for those with an idea and extra cash. Heck, they’ll even supply the idea; they really just want to make T-shirts. With an idea in hand, all that’s required is: 1. a properly formatted file of your graphic; 2. a method (direct print, screen print, embroidery); 3. a position for printing (front/back); 4. an ink color scheme; 5. a shirt choice (style/color); and 6. the quantity (by size). They also need a credit card number, which I imagine one is happy to supply after having successfully burrowed all the way to level 7. Seriously, the whole thing is made as simple as possible. Now understanding the process, and with a couple production companies in mind, I set about creating my design.

The graphics for this one will just be text. Easy, right? … you try it. The challenge here is that, if all you have is text and you want your message to stimulate something, you had better get that font right. Fonts are the product of typography; a complex & nuanced art form, or a cunning & manipulative science depending on your perspective. And perspective - the way we look at things - is key. After all, you are trying to send a message that will stick!

Fonts help the message stick

And here’s where fortune smiled upon this Project. William Morris was, himself, a self-taught typographer. During his printing days at the Kelmscott Press, a high end book publishing business and the last of his creative endeavors, he developed three new fonts (Golden, Troy and Chaucer), as well as a series of elaborate initial letters for use at the beginning of chapters. Morris thought carefully about typefaces and was among the first to use photography in their development. His most treasured of the Kelmscott types was Troy. Described as “semi-Gothic” this design was modeled after a few of his favorite medieval typefaces. In his own words, Morris intended Troy to “redeem the Gothic character from the charge of unreadableness which is commonly brought against it”.

Morris’s Troy font

I decided to make Troy the font for this shirt and found a free download for my Mac. I also downloaded the William Morris Initials font too, just for fun. As to the actual design, my idea was that the text could be displayed on the back of the shirt in three lines. I started with no capitals as the quote, itself, was merely a sentence fragment. However, Morris did choose to capitalize the word “Art” at all instances in that 1884 pamphlet. Anyway, a bunch of iterations were sampled, six of which are shown below.

Trial designs

They all looked fine but, in order to pick one that I would be willing to live with, I needed to think more deeply about the function of the font.

1. The font should make the words memorable, and spark interest - all designs check that box.

2. The font should make the message unambiguous - uh-oh. There is potential for confusion with the unpunctuated fragment “win back art”, due to the polysemantic nature of the words back and art. For instance, given the dorsal location of printing, might one wonder about some sort of “back” art contest underway? What does it take to win it? Or, a reader might ask: who is this Art guy? Is he being held hostage? It’s tricky. I think a no caps version could serve here as that assigns “art” to be an improper noun, but that also happens to be the most boring choice. Using color for the capital “A” in Art would properly focus attention on that word, instead of “back”, and perhaps indicate it to be other than a person’s name. I liked that. A red colored initial letter was used frequently during the heyday of medieval monastic calligraphy. However, according to Fiona MacCarthy in her captivating 1994 book, William Morris: A Life For Our Time, Morris did not favor this practice and only used it on one occasion when publishing a collection of poems by Wilfred Scawen Blunt, a middling poet who at the time was also moonlighting as Morris’s wife, Janey’s, lover. Hmm … Despite the dubious endorsement, I think that is the right choice for this shirt. As a final touch, I tried giving the text a background block so that it might look good on dark colored T-shirts, as well.

And that is where I left things for the summer as I worked to finish some deadline projects and jetted off on vacation. Back in June, I had told my sons of the idea, thinking they would get a kick out of it, and even shared my test creations for their comment. They must have feared that I would let this idea languish for they secretly took it into their own hands and finished the Project for me. Much to my surprise I was gifted with the T-shirt on my recent birthday. What a nice surprise! They used a T-shirt vendor this time, and also added a new “Red Top Workshop” logo, in Troy, on the front. I love it, and plan to print more (let me know if you are interested).

Thanks Ben & Andrew!

The Karabitsu

Here’s an interesting item that’s been on my build list for a few years. It’s a modest sized chest from Japan that I will use for storing firewood next to the hearth. Like most Projects, a little background research is rewarded with new appreciation for the enduring influence of former times. The story follows.

Karabitsu (or kara-bitsu) is a Japanese term that reportedly translates to '“foreign coffer”. I’ve also seen it expressed as “Chinese coffer” or “Chinese chest”, and some believe that kara may even come from kan which, for a time, was a word used to refer to the Korean peninsula. I don’t think we need to propagate confusion here, though. According to the book, Tansu: Traditional Japanese Cabinetry, the karabitsu has existed as a recognized form in Japan since the Nara Period (645-794) and I would imagine that “foreign” in eighth century Japan pretty much meant “Asia”, anyway. Still, it is curious that no non-Japanese examples of the “foreign” coffer pre-dating the Nara era have been found. The term wa-bitsu (Japanese coffer) dates back to the year 1050 and describes a legless form of the karabitsu. Even alongside the “native” wa-bitsu, and the wealth of tansu forms that followed, the karabitsu remained popular in Japan for centuries, serving as storage chests for special objects, often highly decorated with inlays or painted lacquer. I discovered this form while perusing the wonderful reference book: Traditional Japanese Furniture, A Definitive Guide, and there are many fine karabitsu examples to be found on the internet. Some versions sat on tall legs, often six in number, which grew stouter as the form became more ornate. It is a striking chest.

Karabitsu example reproduced from: Koizumi K. Traditional Japanese Furniture, A Definitive Guide, K. Koizumi, Kodansha International: Tokyo, 1986.

Design

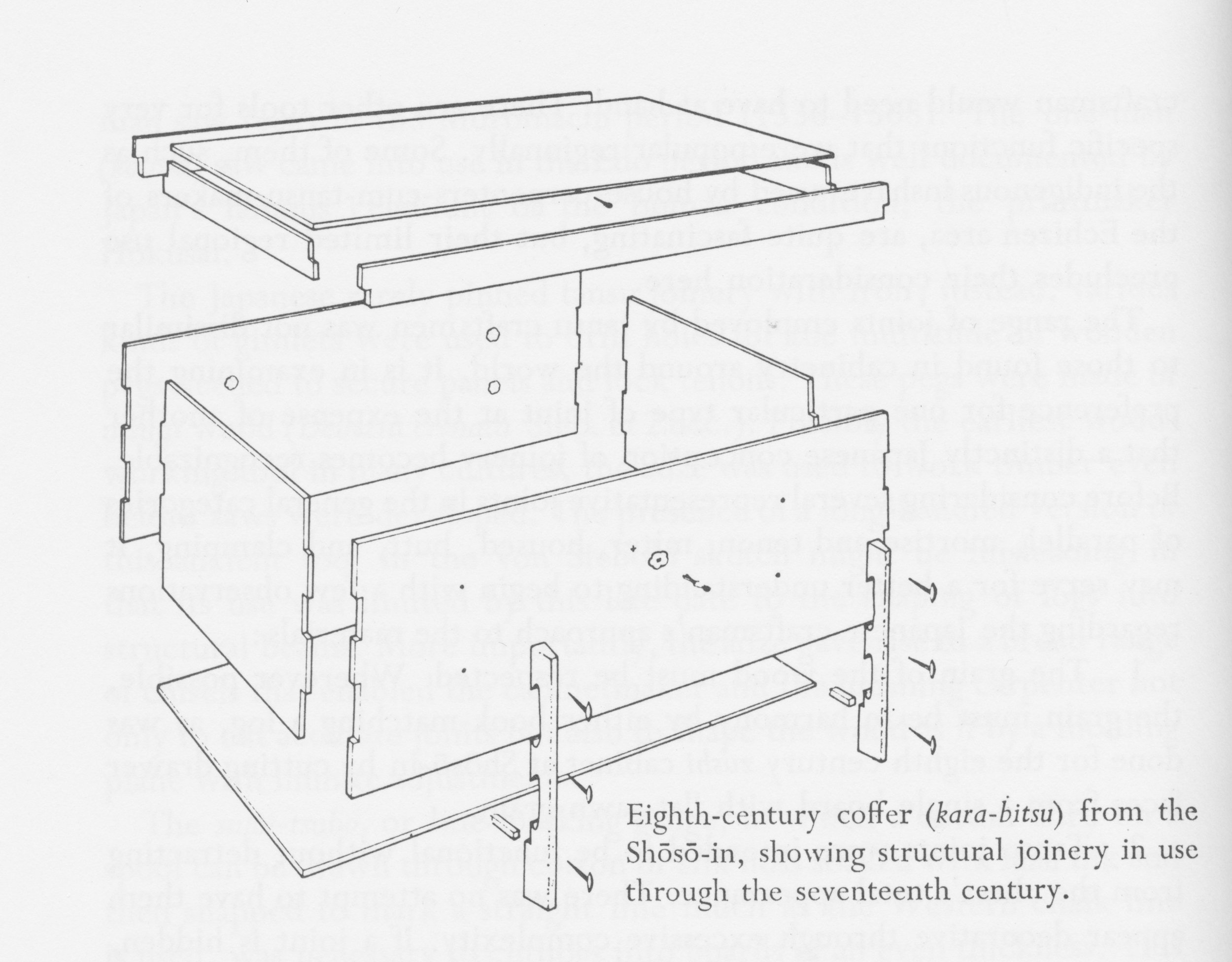

My karabitsu would sit on four legs and be unpainted. That makes it closer to the eighth century original in form, and, as fortune would have it, an example from that time still exists. It seems an imperial warehouse on the grounds of the Todai-ji temple in Nara, dating from that eponymous period, was discovered to contain four intact furniture pieces, and included in these was a karabitsu from which the construction techniques could be gleaned. Quite a find! I show a photo of that piece along with an exploded-view diagram below (reproduced from Tansu: Traditional Japanese Cabinetry).

Earliest known karabitsu?

Anatomy of an early karabitsu

I’ll use this plan as a starting point. The corner joinery was my biggest question and it appears they used simple “box joints” here. I’ll do the same. Iron nails were used to attach the leg pieces to the sides and a brace ran between these legs to support the floor board. The legs of the original also contained cut-outs through which rope could be threaded, allowing the chest to be carried by two people using a cross pole. Instead, I’ll opt for the decorative metal handles used on later examples and lengthen those legs a bit for height. Likewise, I will hinge the top for ease of access, as was the practice in subsequent centuries, and mine will also have a floor board housed within a dadoed groove for strength. In the end, the design will have a few changes brought about by what has become possible with new tools and materials over the millennia, but not wholly different from ancient times.

Karabitsu firewood box, rough plan

Materials

The thirteen hundred year-old karabitsu used zelkova (a member of the elm family) for the legs and cryptomeria (Japanese cedar) for the box parts. These are common woods in Asia, used extensively for tansu and other furniture pieces. However, they are not common in North America and so I would need to find substitutes. I wanted to use special wood for this chest; something that would look nice with a simple oil finish and that would be resistant to insect damage. I decided to try Spanish cedar for the legs and Southern cypress for the box. Not common boards, but ones carried by my favorite yard for unusual lumber, Goose Bay Sawmill and Lumber, Inc. For the handles I would use some authentic hardware picked-up on my last trip to Korea, and I would source the hinges from an Etsy-based craftsman.

Spanish cedar and Southern cypress boards (in lock-down)

Dimensioning

Construction on this Project divides itself neatly into three jobs: the box; the lid; and the cradle (for lack of a better descriptor). They should be made in this order, too, for the dimensions of the box dictate those of the subsequent elements.

the Box

To make the box I first prepped cypress boards to be 5 in. wide, 5/8 in. thick and “square” all around. Before cutting to final length, though, I needed to make a decision on where each board would be placed. I wanted to show off the wonderful grain, of course, but do so in a way that would alternate the orientation of the growth rings to reduce the effects of warp. Once the position puzzle was solved each board was labelled with tape.

Cypress boards positioned and labelled

In order to form the box joints, the top and bottom boards from the front and back faces and middle board from each side face were cut to their exact lengths, 24 and 15 in., respectively. These define the length and depth dimensions of the box. Using a dado blade at the table saw I then created a 5/16 x 5/16 in. rabbet on the backside of both ends of the boards. When mated at the corners, these would form a double rabbet joint, a bit stronger and better looking than the butt joint connection found in a typical box-jointed case. With the “long” boards rabbeted I could make an exact measure of their interior spans, which would define the lengths of the “shorter” boards. Weaving together side boards of alternating length serves the function of a box joint, mating edge grain with edge grain, to form a stronger glue bond. The shorter boards were cross-cut to size and then dadoed to form the same rabbets on their ends. One final cut to house the plywood floor board was needed prior to assembly. For this, I used a dado blade at the table saw to create a 1/2 in. wide x 5/16 in. deep groove near the bottom of the four lowest boards. A piece of 1/2 in. furniture grade birch plywood was then cut to fit the final dimensions. Lastly, I added biscuit slots along the board edges to assist in the assembly.

Box parts cut to final dimension

Assembly of the box proceeded in layers, beginning at the bottom. There are no box joints nor biscuits in this layer and so the floor board is the primary reference for squareness. It was sequentially snugged into the glue-filled groove on each side board and this construct was then squared-up by adjusting the diagonal dimensions across the top. Once all was good, clamps were employed to hold everything tight during the cure. Getting the first layer “right” is key.

Glueing and clamping layer One

The second and third layers stacked on easily with the biscuits to keep everything aligned. After all of the glueing was finished, the sides were hand planed a bit to level everything off and then 3 cherry pegs were inserted on the ends of every long board, in keeping with the Japanese method. The whole body was then sanded to 220 grit.

Completed box

the Lid

The lid for this box will consist of a platform top surrounded by trim around the edges. The original karabitsu appears to have had the top resting atop the “trim”, which acted as a surround for the box. But, since I would be using hinges to keep the top in position I did not require the surround feature and so I decided to use the trim to hide the end grain of the top boards and overlap just a bit with the box when closed. I also decided to make the trim from Spanish cedar to provide a bit of color contrast there.

Construction of this element was simple. I first prepped four cypress boards to be 4 in. wide, by 5/8 in. thick, by 25 in. long. The boards were then positioned to get the desired grain orientations and biscuit slots were cut to assist during assembly. Following glue-up, the ends were trimmed to 24 1/4 in. using a track saw. I prefer this tool to the table saw for cross cuts on large boards such as these, given that I do not have an extension on my saw’s table, however, the rip cut to fix the top’s width at 15 1/4 in. was performed there. Once cut to the final size the platform was sanded to 220 grit.

Platform complete

There are many ways to hinge a lid of this type. My desire was to not show hardware on the exterior of the chest, and so I opted for full inside mount strap style hinges, procured from the Lock and Box Shoppe, a small business found on Etsy.

To attach the hinges I first knife-marked their ideal location along the top edge of the back side and then scribed a 1/8 inch depth mark at this location. The knife marks were sawn down to the scribe line and the interior portion removed with a chisel to create mortises. The result of this operation is to allow the top to sit level when closed. The hinges were then inserted and the screw holes drilled into the back of the box. Next, double-stick tape was applied to the strap portion of each hinge and the lid was laid down carefully into position. With the hinge now taped to the interior of the lid it was lifted free of the box and screw holes were drilled into the lid. The hinges were then temporarily affixed to the lid with a couple of steel screws and this was placed back on top of the box. With my wife, Joung, supporting the open lid I was able to temporarily mount the interior hinge straps with a couple more screws. Everything worked as it should.

Hinged lid in place

Lastly, it was time to fashion the trim. For this I sliced a 1 3/4 in. slab from the side of a 5 ft. long, 2 in. thick Spanish cedar plank. This was re-sawn at the band saw into four ~1/2 in. thick boards which were subsequently thickness planed to a 3/8 in. depth and then ripped to a final 1 1/2 in. width at the table saw. For the joinery, I decided to hide the two front corner seams with miters. Assembly started by cutting the front strip to length on a 45° bias and then fastening it to the top board using finishing nails and a bit of glue. Next the two sides were cut to length and added. The back, ripped at a narrower, 5/8 in. depth to accommodate the hinges, was applied last. Once everything was put together, the top edge was rounded-off and the other edges broken to feel smooth while looking sharp. This completed the lid.

Box and lid

the Cradle

The cradle is my name for the four legs and “chassis” that supports the box. The legs are the stars here so I decided to fashion those first and then figure out the rest of the joinery afterwards. Karabitsu legs act as “stilts”, whose function, I presume, was to lift the box off of a damp, stone Chinese floor. I wanted them to add character to the piece, but nothing overwhelming. After some doodling, I came up with a tapered flare that looked appealing (see rough sketch). This shape was drawn on a piece of 1/2 in. mdf and then cut-out at the band saw and smoothed with a drum sanding bit at the drill press to provide a template. The leg material came from a Spanish cedar board, prepped to 1 1/2 in. thickness. Tracing the template four times onto the cedar and then cutting out these shapes at the bandsaw gave the rough members in a very simple and satisfying operation.

Rough cut legs and template

Next, I glued sides onto the flat edges of the mdf template to convert it into a pattern which could be employed at the router table to convert the rough cuts to a uniform and smooth shape using a flush-trim bit. The edges were then further refined with a card scraper and sandpaper.

Smoothing the bandsaw cut at the router table

The legs would be connected to one another by stretchers made of Spanish cedar. Here I opted for mortise and tenon joinery to keep everything solid and square. It would be tricky to cut the mortises on the curved leg pieces and so I brought out the pattern once again. After attaching an additional mdf leg this could now be used as a jig to hold the karabitsu legs level during the mortising operation. One by one, the cedar leg pieces were screw-mounted to the jig and then a 1/2 x 1/2 x 1/2 in. mortise was cut at the desired position. Easy!

Cutting the mortise with assistance from a jig

For the stretchers I prepped some Spanish cedar to 1 1/2 in. x 1 3/8 in. and then cut two parts to 16 in. length. The tenons were fashioned using a dado blade at the table saw, with the top face of the stretcher cut back further to also accommodate the box edge. For added strength I decided to connect the stretchers with two 1 1/2 in. x 1/2 in. cedar supports. These would keep the cradle structure “square” in the absence of the box and prevent sag of the bottom board. Half-lap joints were used to attach them to the stretchers.

Dry-fit cradle with box in background

Lastly, the design called for visible pegs along the legs. The legs of the original karabitsu were affixed to the box with iron nails, and as the piece was coming together I had decided to use screws here, instead. Screws applied from the outside of the box could have their heads covered with a short dowel cap to achieve the design intent, but I felt that a screw mounted from the inside was the better approach for securing a board to a post. Thus, the pegs would be purely decorative and maybe just one up near the top of each leg would provide the best look. To accomplish this I pounded out a few 1/2 in. diameter Spanish cedar dowels with a dowel plate and used a homemade jig to reproducibly drill a shallow hole into each leg part. The dowels were then glued into place, sawn flush and hand planed smooth.

Final Assembly & Finish

To begin assembly, the half-lap joints of the stretchers and supports were glued together while sitting on the overturned box. This ensured that they would eventually fit, again, during the final assembly. I then decided to finish all components at this stage to better seal the overlapping wooden parts. The plan was to use some sort of colorless product for this but that hardly narrows down the field of contenders. There are a host of appropriate oils, varnishes and oil/varnish blends available these days and so some research was in order. Never having worked with either wood I first queried online and discovered that both are “well-behaved” and easily preserved in a manner that enhances their look. Great! And while that narrows nothing, it also makes it hard to go wrong. On scrap Spanish cedar I tried some boiled linseed oil (BLO) and a product advertised to be a tung oil finish, which is actually an oil/varnish blend that, for all I know, may even contain tung oil. It’s not like they list the ingredients or anything, and I’ve read that snake oil sharps now thrive in the paint aisle. Anyway, this product sold by Minwax gave a nice, subtle luster, less orange coloration compared with BLO and it did well on cypress scraps, too. I liked the look and so I removed the hinges and got to work.

The underside of the box and the cradle chassis were finished first. Once dried, the chassis was aligned and mounted to the box using 4 stainless steel screws through the bottom board. After masking the tenons with tape, I then gave all the remaining parts three coats of the “tung oil” finish over the course of three days.

Finishing the parts

Final assembly proceeded in this order. With the box flipped upside-down, the four legs were glued to the chassis at the mortise and tenon joint. They were then each aligned to be perfectly upright and held in that position by means of a band clamp. I also used this opportunity to drill two 1/2 in. “air holes” in the back, near the bottom, to guard against any hide-and-seek mishaps.

Scene during glue-up

Before the glue cured, I tipped the piece upright and fixed the legs to the cypress box with one screw, each, applied from within. Next, the hinges and lid were attached as before, using the proper screws this time. Finally, reproductions of a classic Korean handle pattern were added to the sides to complete the karabitsu.

This American version of the “foreign” coffer exudes a new pride of heritage, posted by the fireplace to serve today’s special storage needs.

Fireside friend